Scientist of the Day - Réne-Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur

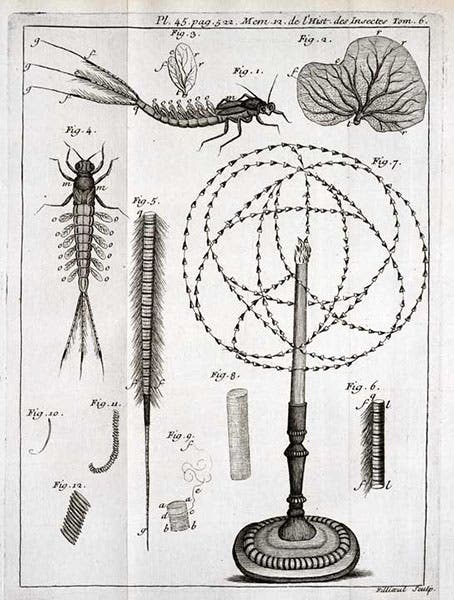

Réne-Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur, a French naturalist, died Oct. 17, 1757, at the age of 74. Réaumur was the premier naturalist of early 18th-century France. His particular forte was insects, which for Réaumur included polyps, arachnids, mollusks, and crustaceans, in addition to the organisms that we call insects. He was particularly interested in parasitic insects, and in peculiar insect skills, such as the leaf-rolling abilities of certain caterpillars and ants. Beginning in 1734, he began issuing volumes of Mémoires pour servir a l'histoire des insectes; by 1742, he had issued 6 volumes, and publication ceased. He had planned on 10 volumes, and started a seventh, on ants, but he never published. The ant volume was finally edited and published by William Morton Wheeler in 1926.

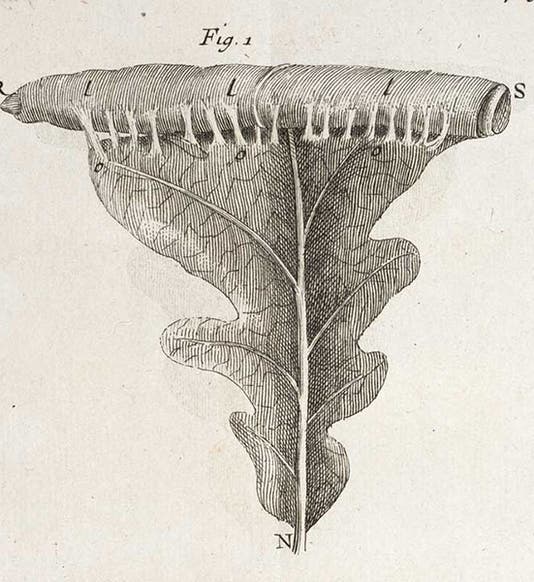

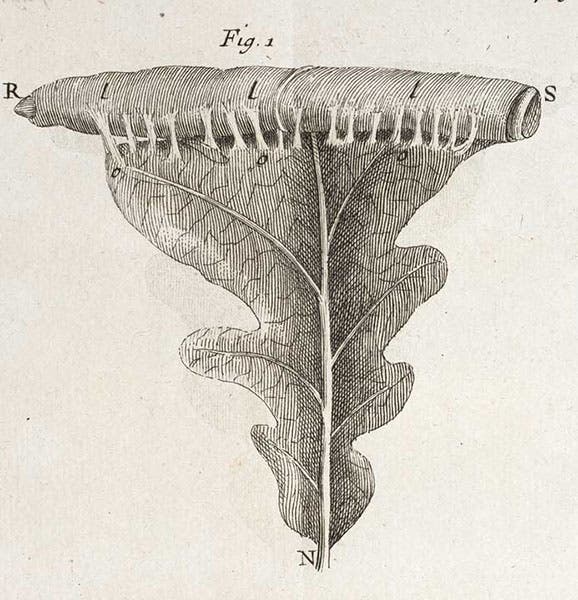

We published a post on Réaumur many years ago, in 2016, but in those days, the images were shown slide-show style, with no captions. So we thought today we would supplement the original 6 images with some new ones, and some details of old ones, all properly captioned. So, for example, in our original post, we included a plate with a variety of leaves in the process of being rolled by caterpillars; here we show a detail of just one of those (first image), so you can see how remarkable the practice of insect leaf-rolling is. We also add here one of the plates depicting the may-fly's remarkable flight pattern, should it come near a candle (second image), as well as the title page to volume 1 (third image).

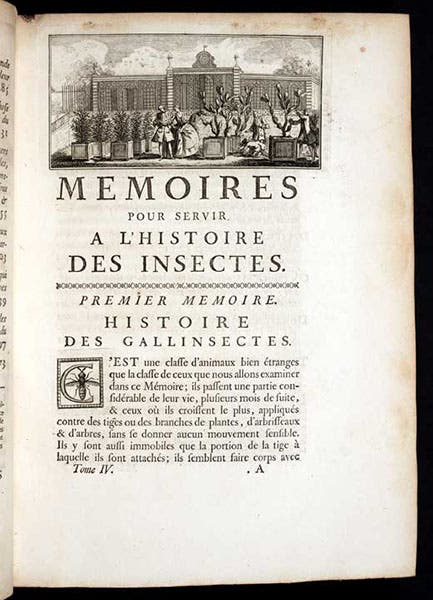

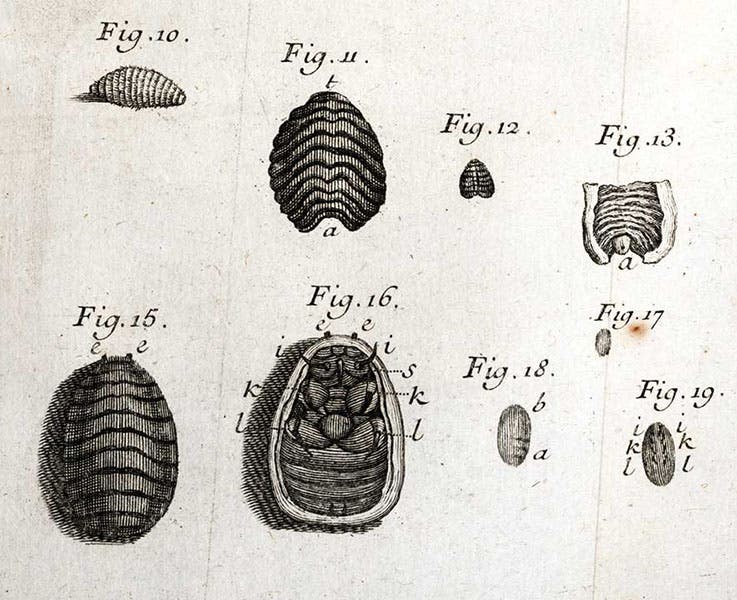

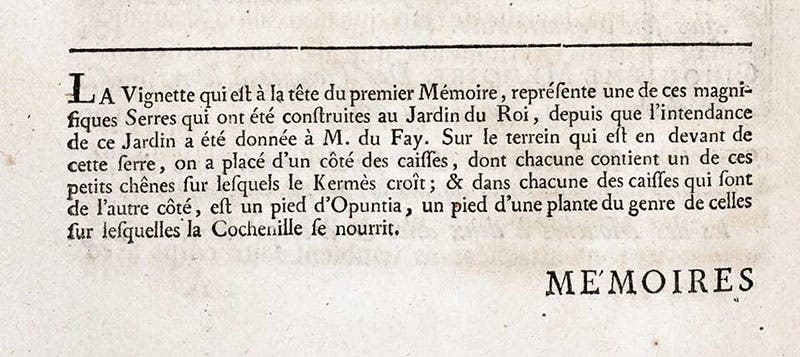

One of the most intriguing features of Réaumur's Memoires are the engraved vignettes or headpieces that begin each volume. We showed you three of these in our original post. I would like to return to one of these, the one that begins volume 4 and presents a display in the Jardin des plantes in Paris of prickly-pear cacti (Opuntia), which provide the feeding grounds for the tiny cochineal insects that produce the brilliant red kermes (carmine) dye. The plants and the insects were endemic to Mexico, and specimens had been spirited out of Central America for the French zoo and botanical garden. You can see just the cochineal headpiece as the first image in our original post; here we enrich the context by showing you the entire page (so you can see why it is called a headpiece, fourth image), a detail of the vignette, so you get a better view of the prickly pears and its denizens (fifth image), and the small legend on the facing page (the end of the preface), which explains the vignette (sixth image). And then, of course, you could turn to the ordinary, non-vignette, engraved plates that depict the cochineal insect; we show you a detail of one of those, so you can see why they are called scale insects (seventh image).

Caption for the vignette that introduces volume 2 of Mémoires pour servir a l'histoire des insectes, by Réne-Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur, explaining the display at the Jardin des plantes in Paris of prickly pear cacti (Opuntia) and the tiny cochineal insects that feed on them, vol. 2, 1736 (Linda Hall Library)

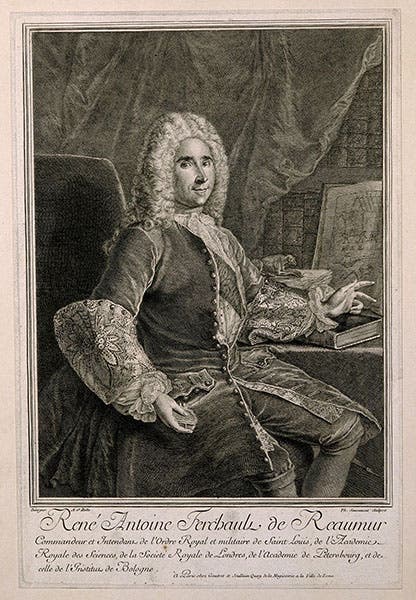

In our first post, we omitted a portrait of Réaumur, for some reason. We add one here, an engraving after a painting from life by Alexis-Simon Belle that is in the Wellcome Collection in London (eighth image).

Réaumur is not widely known today. However, previous generations thought highly of his work. Thomas H. Huxley, the great Victorian comparative anatomist and ardent defender of Darwinian evolution, had this to say about Réaumur in 1877 (on the occasion of Darwin’s receiving an honorary LL.D. from Cambridge): “From the time of Aristotle to the present day I know of but one man who has shown himself Mr. Darwin’s equal in one field of research – and that is Réaumur. In the breadth and range of Mr. Darwin’s investigation upon the works of animals and plants, in the minute patient accuracy of his observations and in the philosophical idea which had guided them, I know of no one who is to be placed in the same rank with him except Réaumur.” If we just thought of Réaumur whenever we think of Darwin, as Huxley apparently did, he would be a much more appreciated naturalist.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.