Scientist of the Day - Raymond Dart

Raymond Dart, an Australian/South African anatomist and anthropologist, died Nov. 22, 1988, at the age of 95. Dart was born near Brisbane in Queensland, Australia, and was in the first class of the just-founded University of Queensland. He then studied medicine at the University of Sydney. In 1920, he served as a demonstrator at University College, London, where he worked with the distinguished anatomists, Grafton Elliot Smith and Arthur Keith, who recognized his talents. After spending a fellowship year in the United States in 1920-21 (second image), Dart was offered a position in the new department of anatomy at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. Although he was not at all keen to head for the provinces, his mentors recommended that he take the job, and he did.

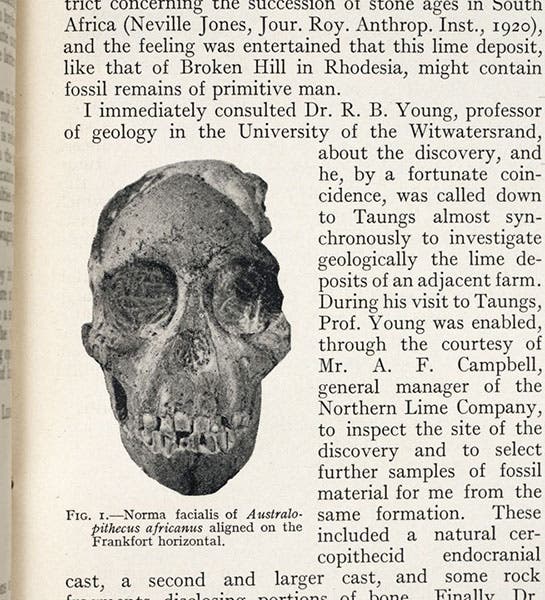

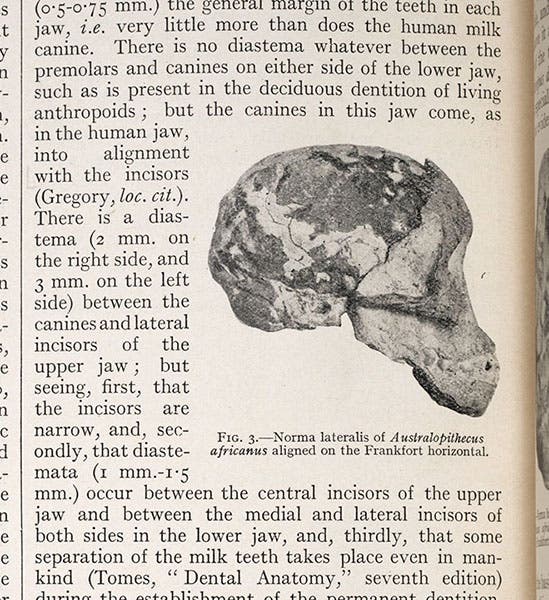

Dart learned from one of his students that fossil baboon bones had been unearthed in a quarry not far away, which was a surprise, for there were no living baboons in South Africa. He decided to study their anatomy, and he was informed, in 1924, that quarrymen in Taungs (now Taung) had blasted a slew of baboon-like fossils out of the limestone; per Dart’s request, they were boxed up and sent to Dart in several wooden crates. When he opened one of them, there was an endocranial cast (endocast or brain cast) of a primate brain right at the top, and although it was small, it was too large for a baboon. After searching through the crate, Dart found a chunk of rock that fit the brain cast, and sure enough, cemented into the rock was a small bony face and a lower jaw, although it took him months to separate the fossils from the chunk of stone. Authorities disagree on the chronology of the discovery; Dart claims he received the box in the summer of 1924, as he was dressing for a wedding; others put the delivery in October, or November. It doesn’t really matter, although I tend to accept Dart’s account.

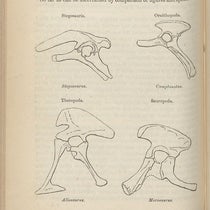

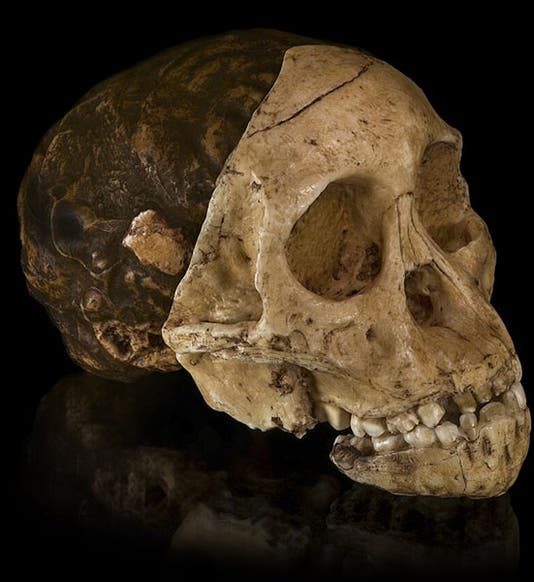

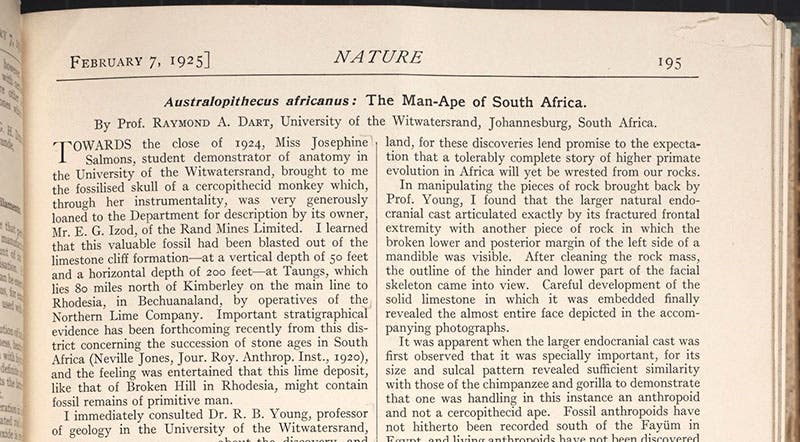

Dart soon realized that he had a new species on his hands (or rather, in his hand), something midway between a young ape and a human child. He quickly wrote up a short paper and sent it off to Nature, the premier science journal of the English-speaking world, where he announced that he had found a fossil primate that seemed to be half ape and half human, and was possibly a prehuman ancestor. He named it, right in the title of the paper (third image), Australopithecus africanus, the South African ape, an odd choice for a species name in this case, since Dart proceeded to argue that it was more human than ape. Moreover, there was evidence that it was a biped, since the foramen magnum, the opening in the skull where the spinal cord enters, was at the bottom center of the endocast, as in humans, rather than toward the back, as in quadrupeds. The Nature paper showed three small photos of the skull and endocast – we show two of those in closeup (fourth and fifth images). We also include a recent photograph of the fossil and brain cast, which is of much better quality, and in color to boot (first image).

The discovery of the Taung child was a first in several ways: the first specimen of an Australopithcus ever found (and it is a genus still very much in use – Lucy was an australopithecine), and the first prehuman fossil found in Africa. Perhaps because of its novelty, and certainly because nearly everyone in 1924 agreed that human origins were to be found in Asia, Dart's interpretation was roundly rejected – even his mentors in England would not have it. Dart’s only defender was a fellow South African, Robert Broom, who, in 1947, finally discovered an adult hominid, Mrs. Ples, now recognized as an Australopithecus africanus, confirming the validity of the species. Dart was right after all. The Taung child is now estimated to be 2-2.5 million years old,

The original face with jaw that Dart picked out of the rock in 1924, along with the endocast, are kept in a vault of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, or Wits, as it is usually called. Wits paleo-anthropologist Lee Berger, when he had nothing to do during rhe pandemic in 2020, made a video inside the vault, and featured the Taung child fossils. The video is 32 minutes long, but it is well worth watching, providing many visual details, and the insights of Berger, that are far beyond anything we can do here. Here is the link. I will note that we have much better images of the 1925 Nature paper than Prof. Berger had. But everything else is way better in the video.

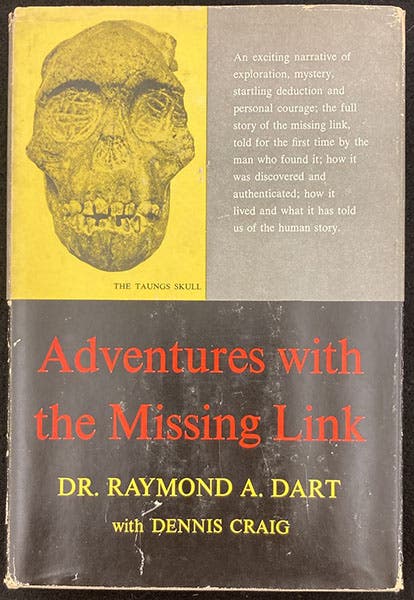

Dust jacket of Adventures with the Missing Link, by Raymond Dart, Harper & Brothers, 1959 (author’s copy)

Raymond Dart’s autobiography, Adventures with the Missing Link, was published in 1959. I don’t know as I would recommend the whole thing, but the account of the discovery of the Taung child and the subsequent controversy is well worth reading. Our library has the book, but I show my copy here, because it still wears its attractive dust jacket (sixth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Columbine, hand-colored woodcut, [Gart der Gesundheit], printed by Peter Schoeffer, Mainz, chap. 162, 1485 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/3829b99e-a030-4a36-8bdd-27295454c30c/gart1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)