Scientist of the Day - Raphaelle Peale

Raphaelle Peale, an American painter, was born Feb. 17, 1774. Raphaelle was the oldest son of Charles Willson Peale, the noted Philadelphia painter who not only left us memorable portraits of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, but also founded the first American museum, the Peale Museum, in 1786. By this time, Raphaelle had three younger brothers, named, in order of appearance, Rembrandt, Titian, and Rubens. Charles seems to have been fairly confident that all his sons would be painters, and he was right – all of them lived up to their names, even Titian, who died at the age of 18 in 1798, but not before drawing some Megalonyx bones for Caspar Wistar, and who was immediately replaced by another Titian, born in 1799, who fulfilled his namesake’s promise. Charles and the second Titian, Titian Ramsay, have already been Scientists of the Day, which did not violate the parameters of this column, nor will Rembrandt, when he comes around, since all were skilled naturalists as well as painters. We have also done Rubens, which was more of a stretch, as is Raphaelle today. But we intend to incorporate them all, since the Peale family was one of the unique natural history institutions of the early Republic.

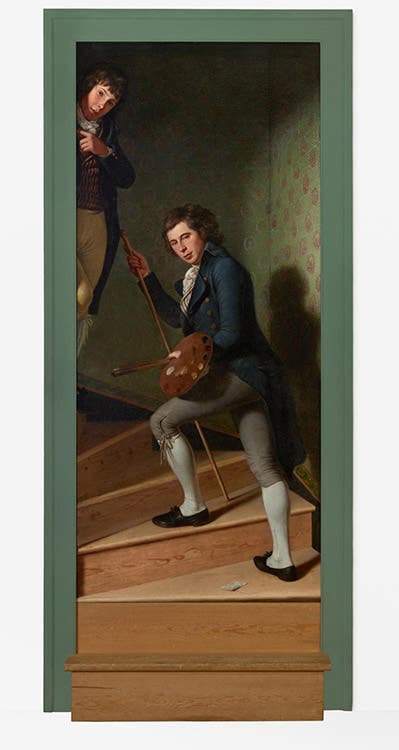

All of the boys were not only artists, but sitters, since father Charles liked to paint them. One of the most charming paintings to come out of the Peale family studio is a trompe l'oeil composition usually called Staircase Group, painted in 1795 (second image). It shows Raphaelle at the bottom of a staircase, with Titian I peeking around the corner at the top. It is meant to fool the viewer, and fool the viewer it does. It fooled visitors to the Peale studio, and it fools people today in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where it now resides. The Museum has accentuated the illusion by adding a real wooden step at the bottom and mounting it on an outside corner inside the Museum, where the viewer can come upon it unexpectedly (third image).

As a painter, Raphaelle is best known as a still-life artist, one of the best at that craft who ever lived. Still lifes had been invented by the Dutch in the 17th century, but by the 1790s, they were a much-deprecated art form. Almost single-handedly, Raphaelle raised the still-life back to respectability, over the protests of his father, who wanted nothing to do with fruit-painting. More than 50 of Raphaelle’s still lifes are preserved in museums around the country; we show two of them here (first and fourth images).

The first one, called Still Life with Celery and Wine, was painted in 1816 and is now in the Munson Williams Proctor Arts Institute in Utica. It has the most amazing apples ever seen in a still life, and they didn’t even make it into the title.

Perhaps Raphaelle's most admired painting is not a still life at all, but another trompe l'oeil composition, usually called Venus Rising from the Sea (ca 1822; fifth image). It is marvelously witty, in addition to being skillfully painted, and you cannot help but try to find the bathing lady through the painted cloth drapery that covers the picture surface. Best of all, for those of you who are local, you can see the painting right here in Kansas City, at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art; it is one of four Raphaelle Peale paintings in the collections.

Raphaelle was a semi-invalid for most of his life, the victim of either gout or arsenic poisoning, and perhaps a fondness for the grape. But he lived until 1825, and in 1817, his indefatigable father captured his likeness in one last family-member portrait (sixth image). It is housed in a private collection known only to curators, but it comes out of hiding occasionally when someone is mounting a Raphaelle Peale still-life exhibition. It has recently been discovered that Venus Rising from the Sea was painted over a copy of Charles Willson Peale’s Portrait of Raphaelle Peale, parts of which reside like ghosts just beneath the surface of Venus Rising. Was Raphaelle subtly telling his father that a good still life is worth more than a good portrait? Or was something else going on here between father and son. One can only wonder, and enjoy.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.