Scientist of the Day - Rachel Carson

Rachel Carson, an American marine biologist, was born May 27, 1907. Carson worked for the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service in the 1940s, and when it was discovered that she could write, her supervisors kept her busy churning out literature about the virtues of nature preserves. I remember visiting Chincoteague, a wildlife refuge on an island off the coast of Virginia, some years ago with my family, and was surprised to discover that the basic introductory pamphlet to Chincoteague had been written by Carson in 1947. Soon Carson realized that she could do just as well on her own, as her book, The Sea Around us (1951), was a huge publishing success. An earlier book, her first book, Under the Sea Wind, which had generated critical approval but no sales when it first appeared in war-torn 1941, was reissued in 1952, this time with much better results for the publishers (second image, below), and her third book, The Edge of the Sea (1955), was a great success as well. Had she quit there, or continued in the same vein, Carson would be remembered as one of the century's better popular writers about nature, a female counterpart to Loren Eiseley, perhaps, or Aldo Leopold.

Dust jacket of Under the Sea Wind, by Rachel Carson, second edition, 1952 (author’s copy)

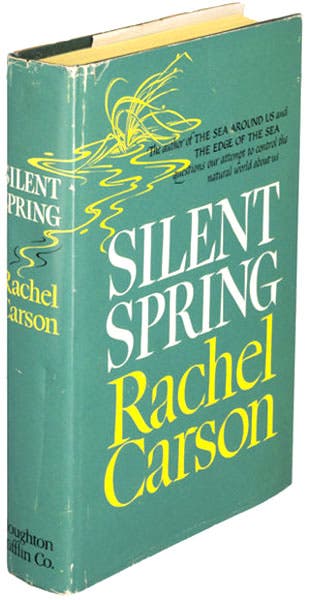

But in the late 1950s, Carson found another calling. She became increasingly concerned about what colleagues were telling her about the damage being done to wildlife by the indiscriminate use of man-made chemicals, especially pesticides. This was a time, one must be reminded, when there was no ecological movement, no Environmental Protection Agency, very little worry about pollution, and a general feeling that science (in the form of the military-industrial complex) could do no wrong. If an area were being threatened by fire ants, then you just dropped poison from the sky and the ants would be taken care of. Hardly anyone, before Carson, asked what else was being taken care of in the process. Carson was a methodical researcher, and she gradually accumulated evidence that pesticides, especially DDT, were killing a lot more than mosquitoes, and that bird populations took a marked hit every time DDT was used. So her next book was not at all a feel-good book about the beautiful fish in the sea. Instead, Silent Spring (1962) was a sound-the-alarm book, a manifesto suggesting that scientific technology could have bad effects as well as good, and an attack on the indiscriminate use of chemicals in the environment.

The book aroused a crescendo of outrage from those in the chemical industry, who threatened to sue publishers, agents, and anyone else involved in such a travesty, and who trotted out their own scientists to argue that Carson was incompetent, a fool, a Communist, and, worst of all, a hysterical woman. Had Silent Spring been a small-press book, by an unknown writer, it might well have just disappeared under the onslaught. But Carson was a highly regarded nature writer, the publisher was Houghton-Mifflin, the book was serialized before publication in the New Yorker, and it was picked up after publication by the Book-of-the-Month Club. It was Carson who came off as the quiet but competent scientist, and the chemical company scientists who appeared as loud and malicious. The Kennedy government came down on Carson's side, as did the subsequent Johnson and Nixon administrations. In 1969, the National Environmental Policy Act was passed, the EPA came into being the next year, and subsequently DDT was banned from commercial use. Unfortunately, Carson did not live to see the ultimate success of her clarion call, as she died of breast cancer in 1964. Her legacy, however, was a huge one – most of the strands of the environmental movement can be traced back directly to 1962 and the publication of Silent Spring. If you are looking for a hero figure for your little girl, Sally Ride is a great choice, but Rachel Carson might be even a little bit better.

There are many portraits of Carson available, but we prefer the one in our first image. The people who design commemorate postage stamps liked it too, for it was used as the basis for the 1981 17¢ stamp that was issued the year after Carson was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest honor a civilian can receive from the government. There were many tributes to Carson on the 50th anniversary of Silent Spring in 2012, but the one that I find most satisfying is a symphonic poem by Steven Stucky, at the time the composer-in-residence for the Pittsburgh Symphony, after many years with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. It is about 18 minutes long, and it will go better if you put your phone into don’t even think about disturbing me! mode. You may listen here.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.