Scientist of the Day - Prosper Mérimée

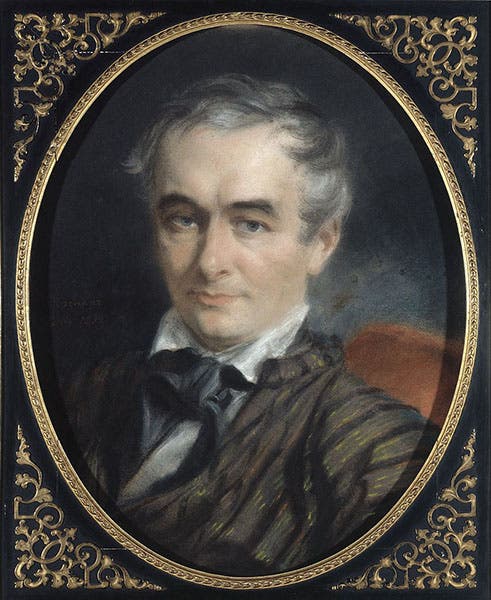

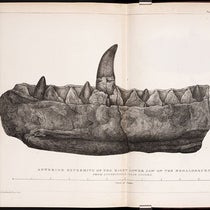

The “Hinds of Chaffaud,” a carved reindeer femur found in Chaffaud cave in Savigne in the commune of Vienne, France, before 1852, now acknowledged as the first discovered piece of paleolithic art, now in the Musée d'Archéologie nationale, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France (musee-archeologienationale.fr)

Prosper Mérimée, a French writer, government official, and defender of France's architectural heritage, was born Sep. 28, 1803. He was quite well known in contemporary literary circles and he participated in most of the important salons in the assorted republics and empires through which he lived. His novella Carmen, published in 1845, was well received in his time, and became even more acclaimed when Georges Bizet fashioned it into an opera after Mérimée’s death.

In 1834, Mérimée was appointed Inspector General of Historical Monuments for all of France, and although he had no particular qualifications for such a post, he was quite assiduous in his duties, travelling frequently to identify historical buildings that should go on the protected list, and acting forcefully to preserve them from would-be restorers or demolishers. The medieval fortified town of Carcassonne is just one of many sites that owes its continued existence to Mérimée.

However, none of this would qualify him as a Scientist of the Day. We include him for one single archaeological act that is not even mentioned in the extensive Wikipedia article on Mérimée. Sometime before 1852, an engraved reindeer bone was found in Chaffaud cave in Savigne in the commune of Vienne. The finders were looking for stone tools, when they came across the reindeer thigh bone, which was delicately carved with the images of two hinds (female deer). They thought it might be a piece of Celtic art, since at the time, there was no known piece of paleolithic art. It would turn out that the Hinds of Chaffaud was the first, and the only person to appreciate that was Mérimée. It came to his attention in 1852; he thought there was something special about it, made a drawing, and sent it in 1853 to a fellow antiquarian in Denmark, Jens Worsaae. Worsae agreed that it looked to be far older that Celtic, and might have been fashioned by the same peoples that made the stone tools that everyone was looking for in the 1850s.

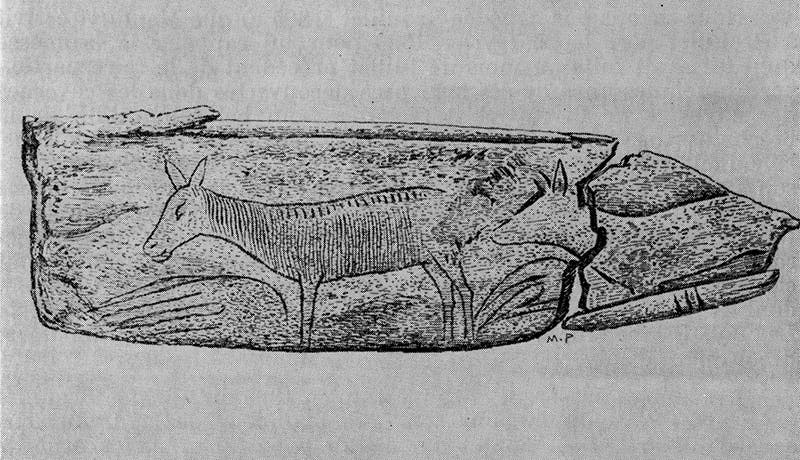

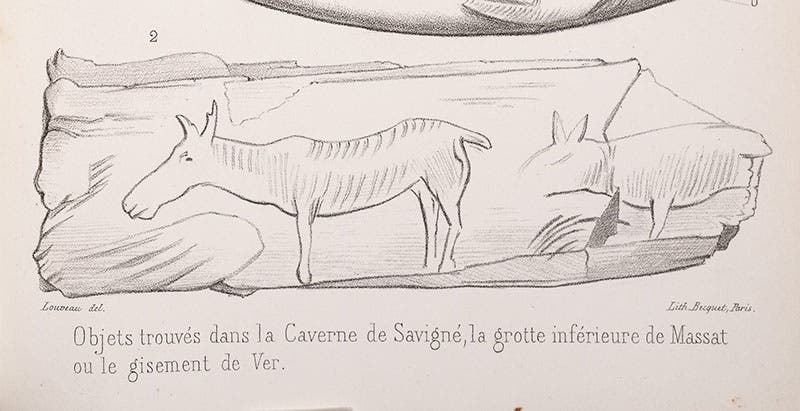

There is an image of Mérimée’s drawing of the “Hinds of Chaffaud” reindeer bone on the website of the Musée d'Archéologie nationale in St. Germain-en-Laye, France, but I don’t know if it is a copy of the original, since they don't give a source for their image (third image). It looks to me to be a half-tone, which would mean it is a later reproduction. But whether or not the original drawing survives, it was the first drawing ever of a piece of paleolithic art, and all honors for that go to Mérimée. We think that Edouard Lartet saw the drawing, because he reproduced it in an article he published in the Annales des sciences naturelles in 1861 (fourth image). But Lartet might have had his drawing made directly from the original bone, because the bone, the first piece of paleolithic art discovered and recognized, has survived down to the present day, and is in the collection of the National Archaeological Museum of France (first image). By the time Lartet wrote his article, dozens of such specimens had been found in various French caves in central France, but only Merimee's bone can be called the first.

There is one other Mérimée achievement that might, with a little stretching, fit into his brief resume as a scientist. In 1841, on one of his inspection tours, he visited the castle of Boussac in central France, accompanied by his friend George Sand, and they found in one of the rooms some moldering tapestries, six of them, variants on a theme of a lady with a unicorn. The tapestries were rescued and cleaned up, and eventually were bought by the state They were moved to the Musée de Cluny, which had been established by Mérimée in the 1840s, and which is now known as the Musée national du Moyen Âge. The Lady and the Unicorn tapestries are among the most famous of all medieval tapestries; we show one that carries the inscription, “À mon seul désir” (fifth image).

Mérimée died in Paris on Sep. 23, 1870, soon after Napoleon III was deposed as Emperor and the Third Republic was instituted. He was just shy of his 67th birthday. Because of his defense of the legitimacy of Napoleon’s reign, his house was burned by a mob just after his death, and all of his papers and possessions were lost. The only bright side of this calamity is that the “Hinds of Chaffaud” reindeer bone and the Lady and the Unicorn tapestries were in safer locations.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.