Scientist of the Day - Pieter Vogelvormer

Pieter Vogelvormer, a Dutch naturalist, was born in The Hague on Apr. 1, 1608. He collected butterflies and beetles as a youth, inspired by the miniatures of the Flemish painter Joris Hoefnagel, and he was further encouraged by Joris's son Jacob, an engraver who met Vogelvormer while visiting the Hague in 1636 on invitation from Count Johan Maurits of Nassau. Maurits was planning an expedition to Brazil in 1637 to set up a sugar factory and study the natural history of the area, and he invited Hoefnagel to come along. Hoefnagel declined, but he recommended young Vogelvormer, pointing out that Pieter was good at collecting and drawing insects and birds, skills possessed by no other member of the expedition. Pieter jumped at the chance to be part of the Dutch Brazil expedition. He arrived in Recife with the rest of the naturalists and artists early in 1637, little knowing that he would not see The Hague again for 12 years.

Things started off well – the Brazilian jungle was rich with new thousands of new species, a collector’s dreamland – but unfortunately, Vogelvormer did not hit it off with Georg Markgraf, another naturalist who was in charge of collecting and drawing mammals, reptiles, and fish. So the Count decided to separate the two, sending Vogelvormer to Quito with a contingent of soldiers to establish a military presence in Ecuador. Vogelvormer’s assigned task was to collect an aviary of exotic birds for the Count’s menagerie back in The Hague. Maurits was especially interested to learn whether even more exotic birds could be bred, so Vogelvormer was instructed to conduct breeding experiments on the birds he collected.

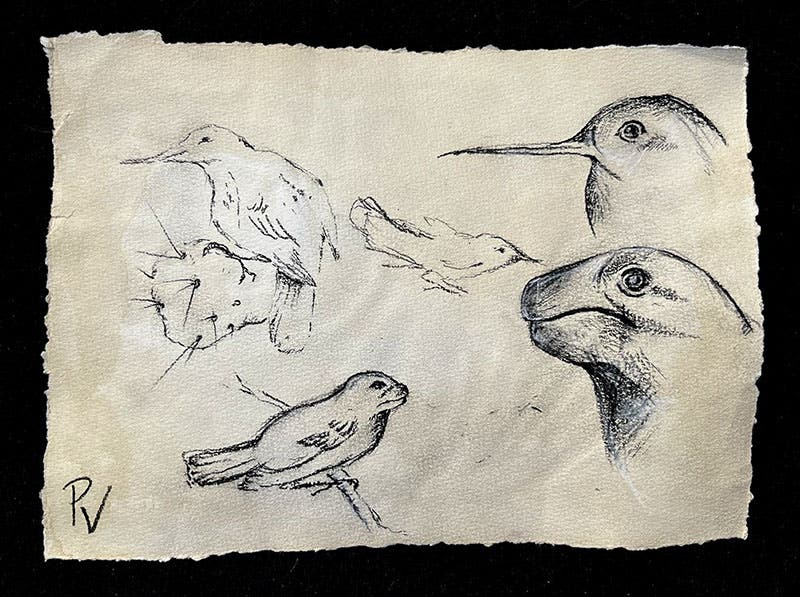

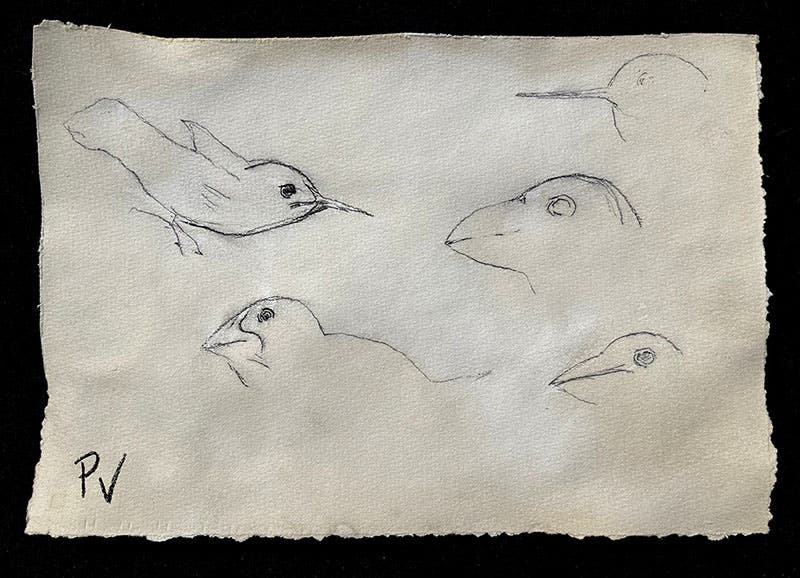

Another leaf with sketches of finches modified and bred in Mauritsstad, Ecuador, by Pieter Vogelvormer; a thorn-wielding finch is on the cactus at left; the turtle-nosed finch at right is one which did not survive long enough on the Galapagos Islands for Darwin to observe and collect it; Mauritshuis Museum, The Hague (mauritshuis.nl/en)

Vogelvormer found that the native finches of Ecuador were easily domesticated, so he began with them. He found that if he made a family of finches peck at their food through small holes in a metal plate, their beaks got thinner and thinner, and they passed this trait on to their offspring. Other finches that had to peck at seeds that were cemented into hard mud, developed quite thick beaks, and their offspring likewise inherited this characteristic. Vogelvormer was able to create finches that fed on cactus, and finches that would eat insects, and he even trained one family to use a cactus thorn to impale grubs. And all of the offspring inherited the new traits. Vogelvormer had plenty of time to breed multiple generations of finches, for the new Dutch enclave in Ecuador, named Mauritsstad, was discovered by the Spanish and besieged, so no one was able to leave.

In what turned out to be a 12-year stay in Ecuador, Vogelvormer bred a collection of exotic finches which were unique, and which would be a stunning addition to the Count's aviary. Moreover, he had demonstrated conclusively that acquired characters can be inherited. When the siege was lifted in 1649, he immediately loaded all his birds into a huge cage built on the deck of a ship, and set sail from Guayaquil for the Netherlands. Unfortunately, a terrible storm arose, and the brig was shipwrecked on the Galapagos Islands just west of Ecuador. Vogelvormer survived, but all the finches escaped, and he was unable to recapture any of them. Fortunately, he was rescued by a passing ship, but when he got back to The Hague, he had nothing to show for his 12 years of work but a few notes and sketches that he had salvaged from the shipwreck. Maurits by this time had been back from Brazil for 5 years and had moved into the palatial home in The Hague that he had built while he was in Recife, called Mauritshuis (fourth image). He was mildly sympathetic to Vogelvormer’s misfortunes, and accepted his notes in lieu of actual birds, but we hear no more of Vogelvormer and his Ecuadorean finch experiments.

When, however, Charles Darwin arrived at the Galapagos Islands almost two hundred years later, he got quite a surprise. He encountered finches with thick beaks, and finches with thin beaks, and insectivorous finches, and even a finch that lived on cacti and used thorns to gather grubs. Since he found these unique species nowhere else in South America, Darwin surmised that they must have evolved there on the Galapagos Islands by a process he would later call natural selection. They would become the crown jewels of his theory of evolution when he began to work it out in 1837 (fifth and sixth images). Little did he or any of his contemporaries suspect that the finches were in fact the crown jewels for Jean Baptiste Lamarck’s theory of evolution by the accumulation of acquired characters. The finches have been misunderstood right down to the present day. But now that Vogelvormer’s notes and sketches have come to light, discovered recently in a drawer in the Mauritshuis (now a renowned art museum), scientists will have to entirely rethink our understanding of the mechanism of evolution.

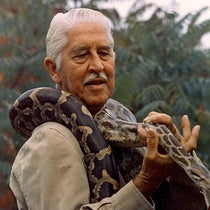

Also discovered in the drawer was an invoice for a portrait of Vogelvormer by a Dutch artist, Jan Lievens, painted in 1636. A portrait of an unnamed Dutch citizen by Lievens can today be found in the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena (second image). We know it is Vogelvormer because the sitter wears a red hat with a feather, and Markgraf, in his field notes from Recife, had written scornfully of Vogelvormer traipsing through the Brazilian jungle in his foppish red hat. It is nice to have a face for this intrepid experimenter, who is going to loom ever larger in the history of evolutionary theory, as we come to grips with his unexpected legacy, now just beginning to command our attention.

Many thanks to Melissa Dehner, graphic designer, for help with this post.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Portrait of Pieter Vogelvormer, oil on canvas, by Jan Lievens, 1629 [1636?], Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena (nortonsimon.org)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/2d91c99f-98df-4c0b-83aa-170c2270f884/Vogel2.jpg?w=425&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)