Scientist of the Day - Pierre Polinière

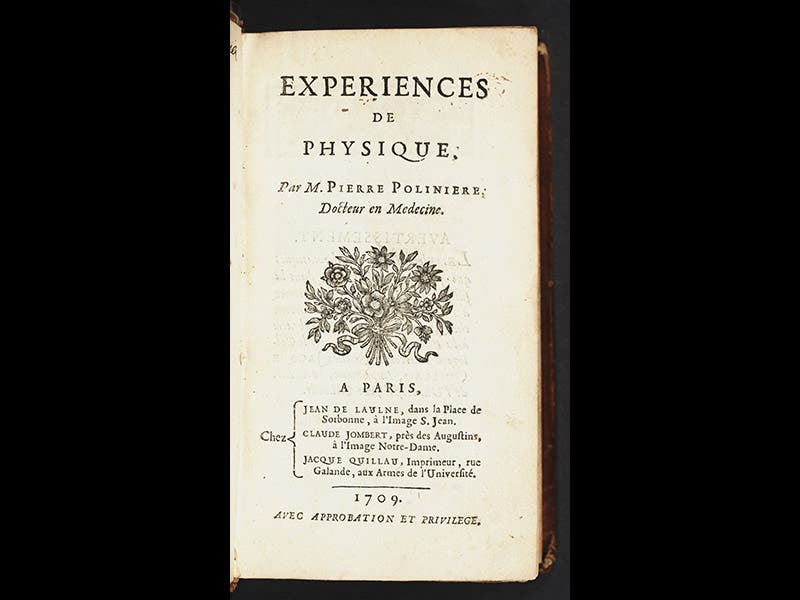

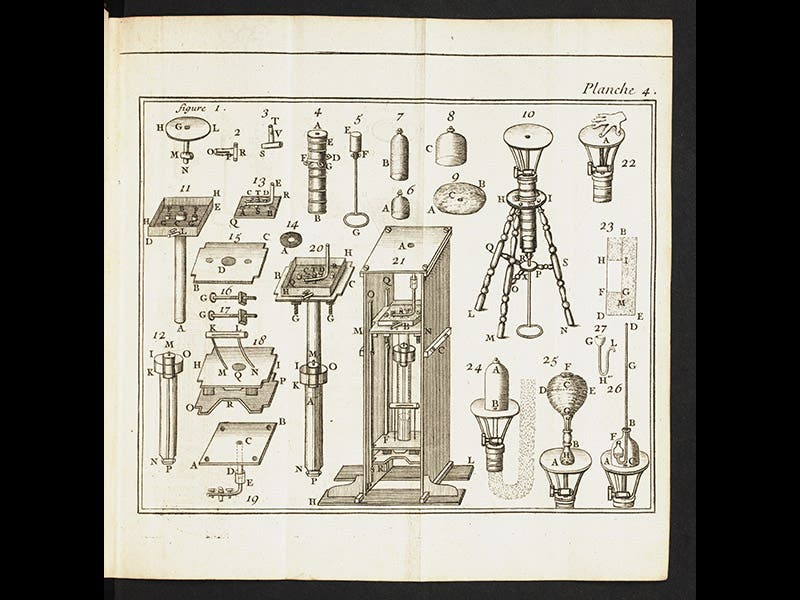

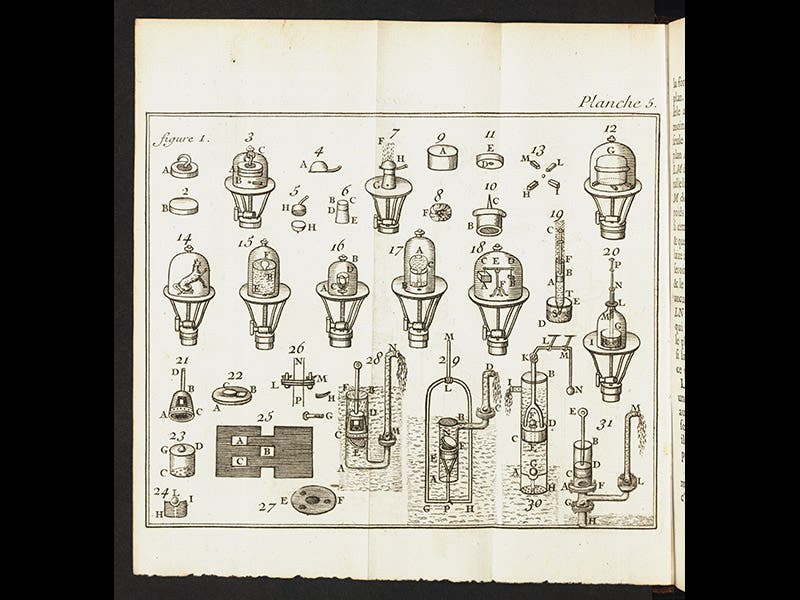

Pierre Polinière, a French physicist, was born Sep. 8, 1671. Around 1700, Polinière began giving experimental demonstrations in Paris to accompany the physics lectures of others, and his public experiments took on a life of their own, drawing a large enrollment. He continued them for nearly 35 years until his death in 1734. Polinière was really the first professor in France to teach physics by way of experiment. In 1709, he published 100 of his experiments as Experiences de physique. For each experiment, he tells you the equipment and materials you need ("Preparation"), the actual experiment you will do ("Fait"), and what it all means ("Explication"). For example, in experiment 43 (fourth image), you are to place a balance inside a bell jar that is hooked to a vacuum pump, and from the balance you are to hang 2 equal weights, one bulky, like a block of wood, and one compact, like a piece of lead (fig. 18). When you turn on the air pump and evacuate the chamber, the side of the balance with the wood on it will go down, and the lead will go up. Explication? The wood, not being very dense, normally displaces a large amount of air, which buoys it up. Take away the air, and it loses this buoyancy, and becomes heavier than the lead, which does not displace nearly so much air.

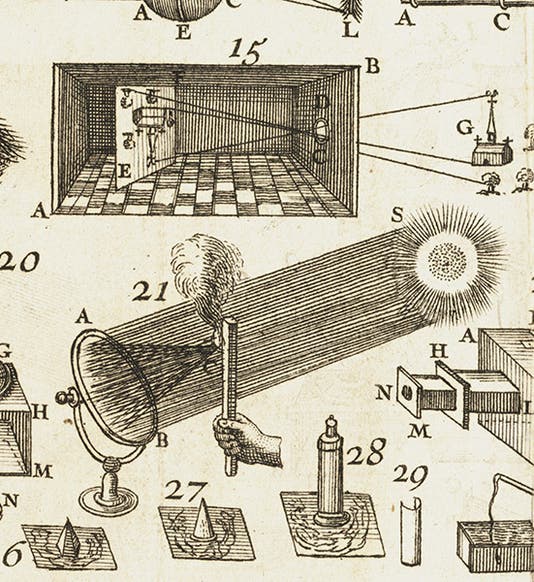

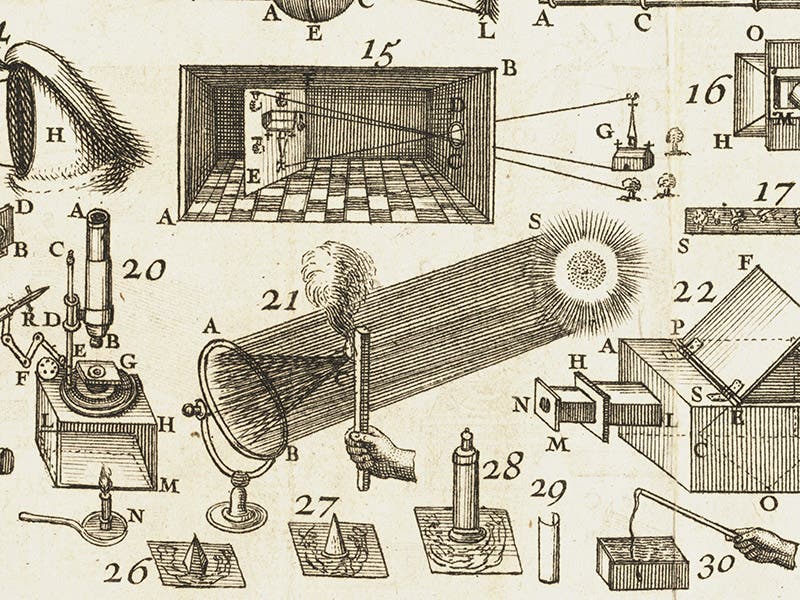

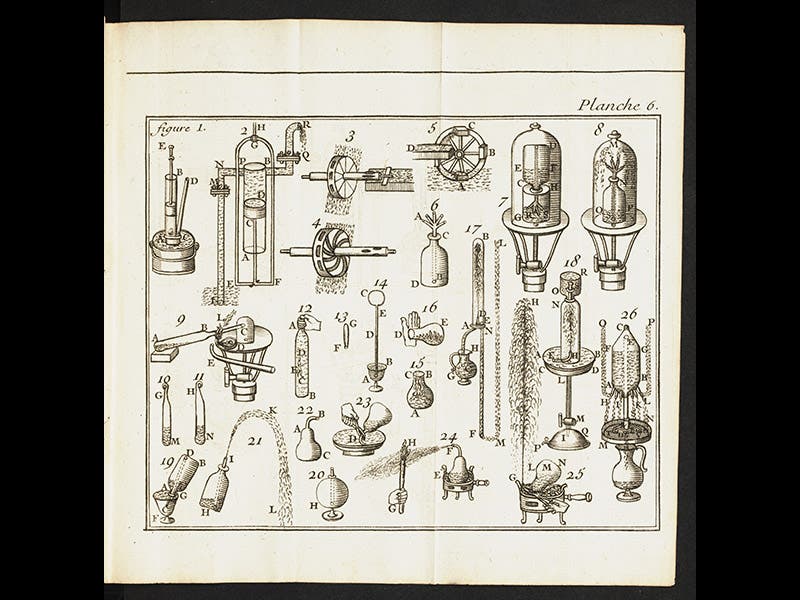

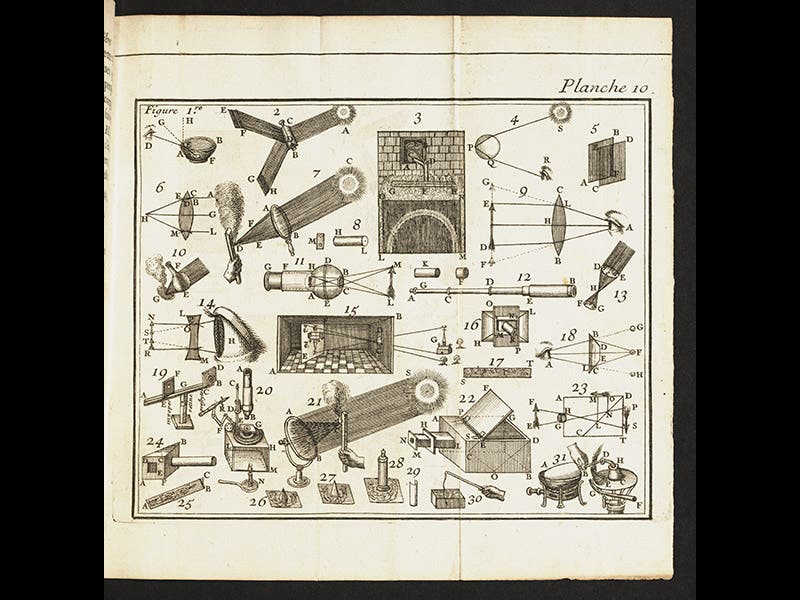

All of the experiments are simple and clever like this one, and one would indeed learn a great deal about physics by performing, or seeing performed, all 100. There are many more pneumatic experiments, including one that involves putting a sealed glass jar in a fire and watching it explode as the air inside expands, and others, less dramatic, that produce a variety of liquid fountains (fifth image). There are a whole series of optical experiments (sixth image). Polinière shows how to make a burning lens, and a burning mirror, and a camera obscura (detail in first image) He even demonstrates how to make anamorphic paintings that must be viewed in a conical or cylindrical mirror (figs 27 and 28).

The Experiences de physique proved to be very popular, and four more editions, each one larger and with more experiments, were issued between 1718 and 1741. We have all five editions in the History of Science Collection, making the Linda Hall Library a paradise for Polinièreans.

One of the curious features of our first edition demonstrates the fickle practice of bookbinding. There are 10 plates in the first edition, and the last page of the text gives instructions to the binder: insert the plates at the end, and bind them so that each plate can be folded out and remain visible when the reader is looking at the page describing the experiment. The binder of our copy paid no attention; he inserted each plate opposite its corresponding page number, so that plate 10 is mounted opposite page 10, even though the experiments illustrated on that plate are described at the other end of the book. And he removed the wide inner margin, so that the unfolded plates do not remain visible when one turns to another page. Fortunately, the plates in our other editions are mounted correctly, so we can demonstrate proper and improper plate placement with different editions of the very same book.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.