Scientist of the Day - Pierre-François-Xavier Bouchard

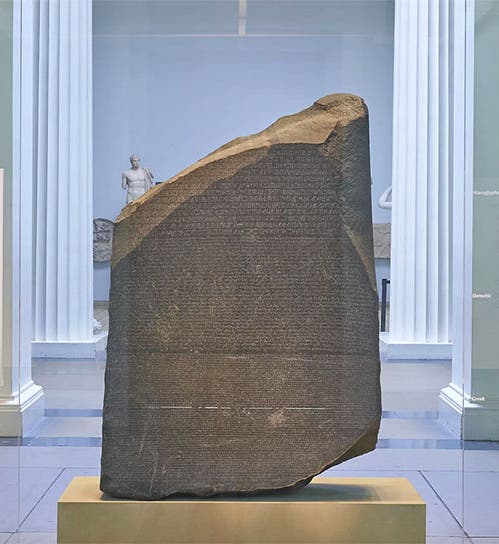

Pierre-François-Xavier Bouchard, a lieutenant and engineer in the French army, was born Apr. 29, 1771. Bouchard entered the army in 1793 and was sent to the school for aerostatics to be trained in military ballooning, a new addition to the art of warfare. There he met Nicholas-Jacques Conté, who was investigating ways to produce hydrogen for lighter-than-air balloons, and who managed to explode a flask of hydrogen in Bouchard's presence. Conté lost an eye; Bouchard had one badly damaged. The Conté connection turned out to be important for young Bouchard, because even though it almost cost him an eye, it also brought him a recommendation to the École Polytechnique, the newly founded engineering school headed up by Claude Louis Berthollet and Gaspard Monge. When Berthollet and Monge were recruited by Napoleon to provide him with talented young engineers for his invasion of Egypt in 1798, Bouchard was one of those invited along. Once they arrived in Egypt with the invasion, many of the engineers became members of the Institute of Egypt, established in Cairo as a scholarly center for the scientific pursuits of the expedition. Bouchard seems to have preferred the military side and had limited involvement with the Institute. In the summer of 1799, Bouchard was put in charge of rebuilding a fort near the port city of Rashid (Rosetta). On either July 15 or July 19, 1799, he found part of an ancient Greek stele built into a wall. It had three inscriptions carved into its dark grey granite-like surface: one at the bottom in Greek, a second in the middle in Demotic, and at the top, broken off, a third in hieroglyphics. Bouchard's discovery is now called the Rosetta Stone (first image). It was one of the great archaeological finds of the Napoleonic expedition, and to Bouchard's credit, he immediately recognized that if the three inscriptions recorded the same text, then it could potentially provide a key for the decipherment of hieroglyphic writing. The stone was taken back to Cairo, and the inscriptions were carefully copied by the members of the Institute, primarily by taking prints directly from the stone, and also by making casts of the inscriptions. The man in charge of making the prints was none other than the one-eyed inventive genius, Nicholas-Jacques Conté.

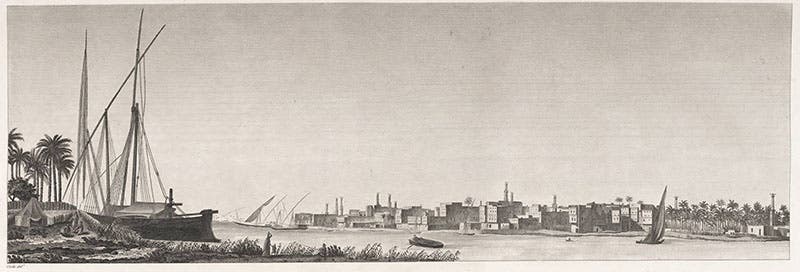

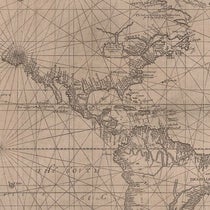

It was a good thing that copies and casts were taken, because when the French surrendered to the British in 1801, the Rosetta Stone, and many other antiquities, were surrendered as well. Which is why, if you want to see the Rosetta Stone, you must go to the British Museum, and not the Louvre. Ironically, it was not an Englishman, but a Frenchman, Jean-François Champollion, working from the copies, who finally deciphered hieroglyphics in 1822. When the scientific and cultural fruits of the Napoleonic expedition were printed up, as the multi-volume Description de l’Égypte (1809-1828), engravings made from the Institute copies were included. They depicted the stone life-size, and even though the volumes of the Description were large, it took three engravings to display the entire stone, one for each language inscription. Here is the engraving of the broken-off top section, with the hieroglyphics. We displayed this plate in our 2006 exhibition, Napoleon and the Scientific Expedition to Egypt, and our online catalog of the exhibition has an extensive section on the discovery, study, and fate of the Rosetta Stone. There you can see all three engravings of the Rosetta Stone fashioned into one, courtesy of PhotoShop, along with some details of the hieroglyphic engraving. There is also a view of Rosetta, taken from the Description, which we reproduce here as well (second image). Bouchard had a successful career as a French army officer, but he never again did anything as exciting as finding a Rosetta Stone. And because he withdrew from the Institute of Egypt in favor of military affairs, he was not included when André Dutertre made pencil sketches of nearly all of the Institute members. Over the years we have profiled quite a few of the engineers who accompanied Napoleon, and we nearly always included the Dutertre sketch of that individual, For example, here is the entry on François-Charles Cécile, who drew the view of Rosetta above; his Dutertre portrait is the last in the slide-show series. But Dutertre never drew Bouchard, so we have no idea what Bouchard looked like. That is a shame; he deserves to be better remembered, and portraits, busts, and statues are a great aid to public recollection. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.