Scientist of the Day - Philippe Bunau-Varilla

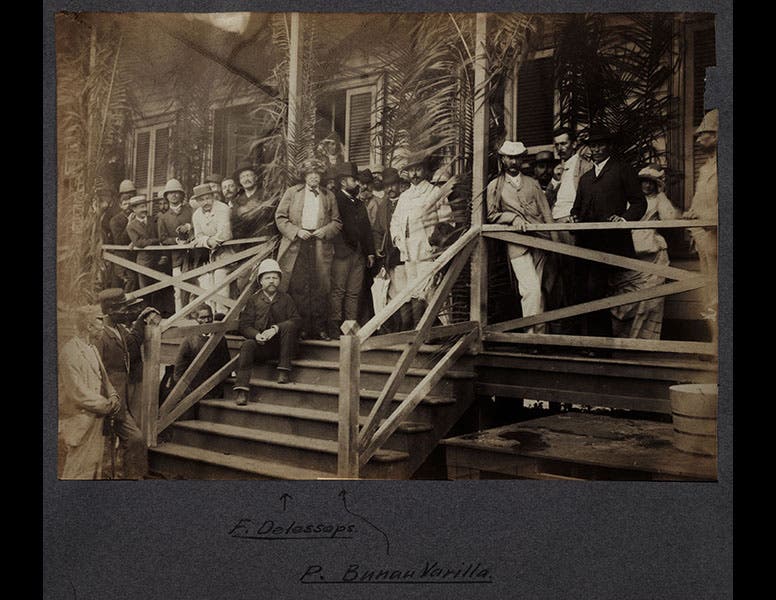

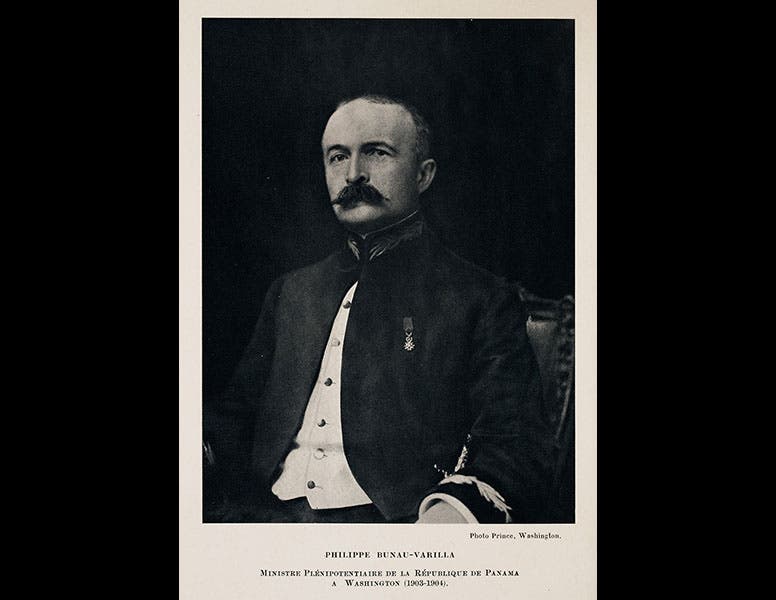

Philippe Bunau-Varilla, a French engineer, was born July 26, 1859. Bunau-Varilla joined the French Panama Canal Project in 1884 and rapidly rose through the engineering ranks, becoming Director General within a year. He is pictured above with the President of the French Canal Company, Ferdinand de Lesseps (first and second images). Lesseps, on the porch, has his hands in his belt, Bunau-Varilla is immediately to the viewer’s right, wearing a bowler.

When the French endeavor, and its successor of the 1890s, came to naught, Bunau-Varilla jumped to a better ship and persuaded Theodore Roosevelt that Panama (not Nicaragua) was the place for a U.S. canal effort. When Roosevelt's government was unable to secure a treaty with Columbia, which then possessed the Isthmus, Bunau-Varilla, with the blessings of Teddy, organized an uprising among Panamanian rebels on Nov. 3, 1903, that established the Republic of Panama. Bunau-Varilla financed the revolution and arranged for American warships to show up at just the right time to prevent Columbia from retaliating; he even wrote the declaration of independence and the constitution for the new Republic--all this from his suite at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York City.

Bunau-Varilla managed to convince the future president of Panama to appoint him as "envoy extraordinary" to Washington with full diplomatic powers, and before a Panama delegation could reach Washington to negotiate a canal treaty, Bunau-Varilla had written his own treaty, which was approved and signed by the U.S. Secretary of State, John Hay (sixth image). By the treaty, the U.S. was granted sovereign rights in perpetuity to a ten-mile strip of land centered on the canal, for a payment of $10 million and an annual fee of $250,000. We might add that the former French canal company, of which Bunau-Varilla was the major stockholder, was paid $40 million for its equipment and right-of-way, so Bunau-Varilla profited handsomely from the deal. The terms, needless to say, were extremely advantageous to the U.S., and all of Panama was outraged, and remained outraged, until the treaty was finally abrogated in 1977. But the United States now had its "Path between the Seas," to borrow the title of David McCullough’s book on the subject, and the Panama Canal would be successfully constructed over the next 11 years.

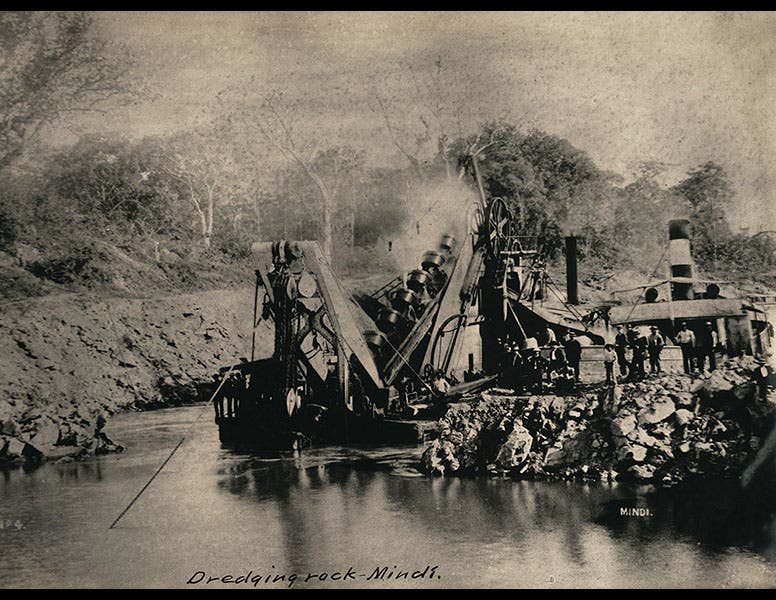

Our Library has an outstanding collection related to the building of the Panama Canal; it is called the A.B. Nichols Collection and consists of many albums of photographs, articles, and records kept by Nichols, the Office Engineer during the entire project. The collection was given to the Engineering Societies Library of New York by his daughter; that library came to our Library in 1995. The Nichols Collection formed the backbone of an exhibition in 2014, The Land Divided, the World United: Building the Panama Canal, commemorating the centennial of the completion of the canal. It may be viewed online. The page that discusses Bunau-Varilla is here.

The first five images above are from the Nichols Collection and depict Bunau-Varilla and several views of the French effort to build a canal that Bunau-Varilla oversaw. We do not have the photograph of Hay and Bunau-Varilla signing their eponymic treaty (sixth image), so we had to settle for a small online version. We would like to see the original, for it appears to some that John Hay's place was taken for the occasion by a wooden dummy.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.