Scientist of the Day - Philip Glass

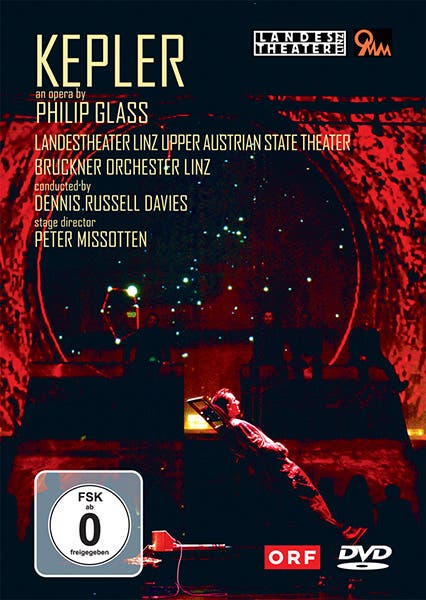

Philip Glass, an American composer, was born Jan. 31, 1937. Glass is a prolific composer of a wide variety of music, including symphonies, concertos, film scores, operas, and chamber pieces. He considers himself a classical composer, although those familiar with Beethoven and Schubert would probably look for some other word to describe Glass's music. He merits a birthday notice in this space because he has written no less than three operas about scientists. The first was Einstein on the Beach, which premiered in 1976. In 2002, Glass gave us Galileo, which presented 10 scenes from Galileo’s life and trial for heresy. Most recently, in 2009, he launched an opera about Galileo’s contemporary, Johannes Kepler, called simply Kepler. Since Kepler is the only one of the three to be released on DVD, and thus the only one I have seen, we will focus on it here, even though the DVD is no longer available.

The DVD recorded a performance in Linz, Austria, the city where Kepler lived during his later years and which commissioned and premiered the work. It is elaborately staged, with the central circular platform in almost constant rotation, in line with the theme of Kepler’s search for an explanation for the motion of the planets. Kepler himself is the only real person in the opera, the other 6 principal singers being the six planets (all that were known at that time), and the chorus representing the ordinary person’s reactions to the mystery of the heavens. The music is what one expects of Glass – percussive, repetitive, syncopated, and at times almost thrumming. But the genius of the work is that Glass tries to capture the underlying motif of Kepler’s life, which was to understand God through his creation, the universe, and to discover the rules by which God brought our world into being. Kepler was convinced that God is essentially a geometer, and that he used geometric principles to determine, for example, that there should be six planets, not five or seven, and to calculate exactly how to space them. Initially Kepler believed that God had used a nest of the five Platonic solids to determine the number and spacing of the planets, and much of the first part of the opera is concerned with this initial solution to the “Cosmographic Mystery” (we once wrote a post on Kepler and his Mysterium cosmographicum). There are not many operas that contain a lyric such as this utterance of Kepler: “To the orbit of Mars I circumscribe a tetrahedron,” while the planets, slowly twirling about on stage, sing “Number, Quantity, Circular motion.”) This scene used to be on YouTube, but it is no longer there. Later, Kepler releases the planets from their circular restraints with his discovery that the planets move in elliptical orbits, and the opera has scenes on this as well. There are a number of still photos of the changing set of Kepler on the website of the stage director, Peter Missotten, which was the source for our third image.

What distinguishes Glass’s Kepler is that Glass tried to juxtapose Kepler’s belief that God’s universe is rational, and that we can discover its rules by observation and measurement, with the ordinary person’s view (the chorus) that all we need to do is read Scripture and we will learn all we need to know (in one memorable lyric, “by closing our eyes, we see further”). Kepler occasionally shows impatience with this attitude (theology gives us authorities, he sings at one point, in exasperation, but philosophy gives us reasons), but in general Glass treats both conventional religion and Kepler’s Platonism with respect, refusing to mock those that prefer their religion on a platter, and this adds considerable dignity to the performance. Glass made some decisions that I would question; there is a scene devoted to astrology and Kepler’s interest in his own horoscope, that does not seem to fit in with the opera’s general premise, and there is a lot of action, if I may bend the contours of the word, that consists simply in the performers looking up in wonder while the orchestra waxes percussive. But the powerful scenes that depict Kepler wrestling with God and the mystery of the heavens more than make up for any deficiencies. The opera has been performed only once in the United States, to my knowledge, at the Spoleto Festival in Charleston in 2012, but wouldn’t it be nice to have its next American performance be at the Kaufman Center in Kansas City.

I thank my musicologist friend Bill Everett for steering me in Glass’s direction, and for lending me his copy of the Kepler DVD years ago, which I should have bought for myself immediately, but did not, and alas, it is now out of print. There used to be several snippets from the opera on YouTube, but now there is hardly anything, merely a few sections from the score but no operatic scenes. It seems a shame that even glimpses of Kepler the opera are so hard to find.

It is interesting that two eminent modern composers have written operas about Kepler: Glass, and Paul Hindemith. We wrote a post on Hindemith’s Die Harmonie der Welt (1955) a few years back.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.