Scientist of the Day - Percy Pilcher

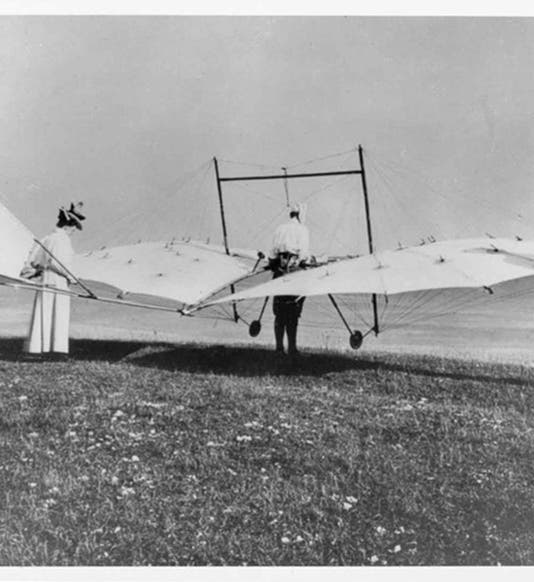

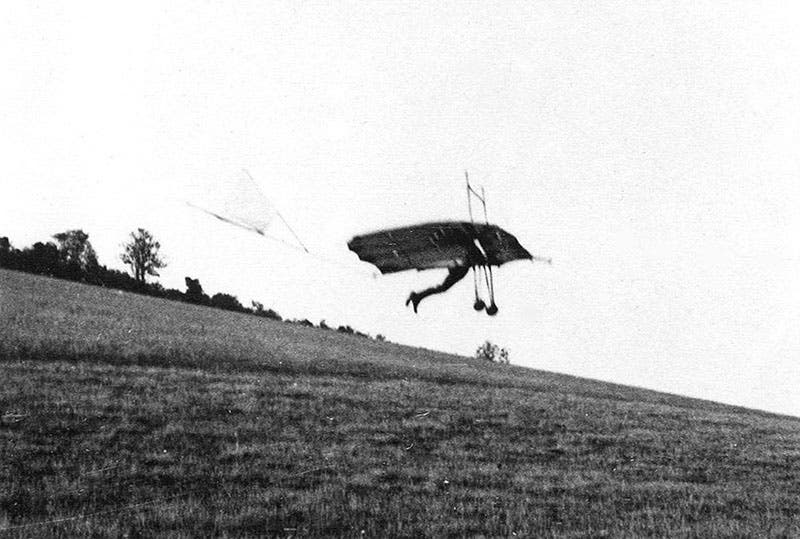

Percy Pilcher, a British inventor and aviator, was born Jan. 16, 1866. Pilcher built and flew his first glider, the Bat, in 1895. The Bat was a hang-glider, like the craft that were being flown in Germany by Otto Lilienthal. Pilcher built and flew three more gliders, the last of which he called The Hawk. As you can see from the photos, a hang glider is basically a pair of wings extending out from a lozenge-shaped opening with a bar across it, from which the aviator hangs his body. Control is achieved by swinging one’s body right and left, back and forth. The Hawk had no ailerons, and, while it did have a tail, there were no elevators on the tail.

With The Hawk, Pilcher achieved a glide of over 800 feet, which was a world record at the time. His first flights took place in Eynsford in Kent, and then he moved his base of operations to Leicestershire, to the grounds of an estate known as Stanford Hall. Several surviving photographs show Pilcher in flight in The Hawk (third image). In 1899, Pilcher turned his attention to powered flight, and he equipped a tri-plane glider with a low-power engine, which he hoped to demonstrate for potential investors. When the demonstration day of Sep. 30 arrived, and his powered plane was not ready, Pilcher decided to wow his audience with a flight in The Hawk instead. He was only 30 feet off the ground when the tail broke away, and The Hawk plummeted to earth. Pilcher was severely injured in the fall and died two days later. He was 33 years old.

Of all the early aviators – Lilienthal, Orville and Wilbur Wright, Octave Chanute, Samuel Langley – Pilcher is by far the least known. Has he been unjustly overlooked? He was the first person in Britain to design, build, and fly heavier-than-air craft. Should he be getting more credit? Some think so, and his fans have erected monuments at Eynsford and Stanford Hall to commemorate his achievements and his death. The monument at Stanford Hall marks the spot where Pilcher fell to earth in 1899. The sheep do not seem to be an appreciative audience.

Pilcher has attracted a biographer, Philip Jarrett, who thirty years ago published Another Icarus: Percy Pilcher and the Quest for Flight (1987). In his book, Jarrett did not try to turn Pilcher into a neglected hero; rather, he pointed out why the Wright brothers succeeded and others, including Pilcher and Lilienthal, did not. It basically came down to this: before they ever attempted to put any engine on a glider, the Wrights sought first to master the problem of control. Only when they were confident that they could fully control their gliders, did they seek to add power. The hang-glider people, on the other hand, paid little attention to the problems of control, perhaps because, if you are gliding in a straight line down a slope, shifting your weight is sufficient. But it clearly is not when things go wrong, as both Pilcher and Lilienthal discovered the hard way. Three years before Pilcher fell to his death, Lilienthal had met the same fate.

We were surprised when the Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame opened to the public in 2011 and announced their inaugural class of seven inductees. There, amidst the likes of Thomas Telford, Lord Kelvin, and James Watt, was Percy Pilcher. I am not sure what surprised us more – the suggestion that Pilcher was in the same league as Telford and Watt, or the implication that Pilcher was a Scot. He did spend four years in Glasgow, 1891-95, as an assistant at the University, and he did fly the Bat during this time, but he was born in Bath and died in England, did all the rest of his gliding in Kent or Leicestershire, and is buried in London. The only other Scottish connection we could discover is the location of the original Hawk, which is in the National Museum of Flight in East Lothian (although no longer on display). If that is all you need to establish citizenship, then we might as well induct sculptor Henry Moore into the Kansas City Hall of Fame. Which, now that we raise the point, is not such a bad idea.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.