Scientist of the Day - Paul Popenoe

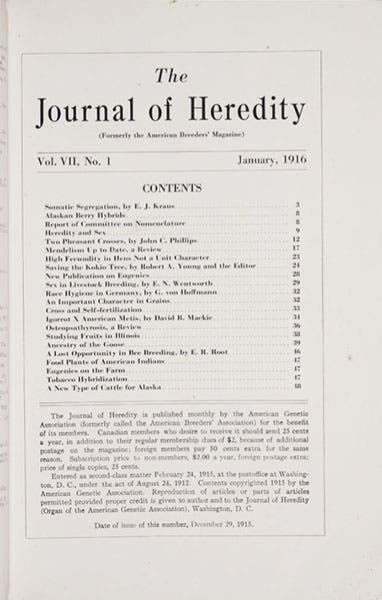

Paul Bowman Popenoe, an American scientist specializing in plant exploration, heredity, and eugenics, was born Oct. 16, 1888 in Topeka, Kansas. Initially, Popenoe worked as a journalist and plant explorer collecting date palms in the Middle East and northern Africa. But in 1913, David Fairchild, America’s foremost plant explorer and president of the American Genetic Association (originally named the American Breeders’ Association), hired Popenoe to work as editor for the AGA’s publication The Journal of Heredity.

The American Genetic Association brought together high-ranking bureaucrats, leading scientists of the day, and professional breeders, with a common mission: promoting genetics and the laws of heredity in order to improve plant, animal, and human racial stocks. It boasted an elite membership with government officials such as Assistant Secretary of Agriculture Willet M. Hays, prominent scientists including Charles Davenport and Alexander Graham Bell, and private plant breeders like Luther Burbank. As the first scientific organization in the United States to recognize the importance of Gregor Mendel’s laws of inheritance and support eugenic research, the AGA actively intertwined eugenic ideas about racial purity with agronomy for the purpose of shaping both America’s farms and human society.

While his brother Wilson went on to a career at the U.S. Department of Agriculture as a full time plant explorer, Paul’s role as editor propelled him to a nationally recognized authority on eugenics, national health, and family life. Drafted into the army in 1917, he served as a captain in the War Department’s Commission on Training Camp Activities, in the section on vice and liquor control, working to prevent soldiers from indulging in alcohol and prostitution. In addition to battling vice, Popenoe co-authored the textbook Applied Eugenics, which appeared in 1918.

After the war, Popenoe moved to New York, where he worked for the American Social Hygiene Association, using public education to promote premarital abstinence. While in New York, he met a young dancer named Betty Stankovitch. They married in 1920, after six months of courtship. Seeking to escape the licentious environment of post-war New York City, Popenoe convinced Betty to relocate to the Coachella Valley to farm dates and cotton. After six hard years, they abandoned their desert ranch and moved to Pasadena, California. Popenoe shifted his efforts back to intellectual pursuits, working for the Human Betterment Foundation, an organization promoting compulsory sterilization. The 1920s were a prolific time for Popenoe in which he authored several books on marriage, reproduction, and family life including Modern Marriage (1925), The Conservation of the Family (1926), Problems of Human Reproduction (1926), Sterilization for Human Betterment (1929), and The Child’s Heredity (1929).

In 1930, Popenoe struck out on his own, founding the American Institute of Family Relations. By the mid-1940s, Nazi enthusiasm for eugenics had widely discredited it as a serious science. Popenoe responded by shifting his interest from the genetic improvement of society to improving marriages. No longer able to advocate directly for hereditarian values and eugenic marriages, he worked to uphold the institution of marriage itself. He established himself as the leading expert on couples therapy and co-authored the popular Ladies Home Journal feature “Can This Marriage Be Saved?” Although the first in the United States to formally adopt the term “marriage counselor,” Popenoe admittedly borrowed the concept from German scientists who began instructing couples in the 1920s about the eugenic or dysgenic impact of their unions on the nation. Championing marriage and procreation, Popenoe’s work proved a direct outgrowth of his lifelong efforts to promote heredity and the cause of “better breeding” in America.

You may learn more about Paul Popenoe, David Fairchild, breeding, and plant exploration at a lecture hosted by the Library on Tue., Oct. 23, 2018: “The World of Our Dreams: How America’s Plant Explorers Transformed Our Farms and the Food We Eat.”

Dr. Rebecca Egli is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the Linda Hall Library. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to raegli@ucdavis.edu.