Scientist of the Day - Paul Manship

Paul Howard Manship, an American sculptor, was born Dec. 24, 1885, in St. Paul, Minnesota. After a local apprenticeship, Manship won a competition to study in Rome, where he spent three years and was profoundly influenced by archaic and classical Greek sculpture. He came home, went to New York, and began to develop a style that would eventually become known as Art Deco. He often sculpted animals, which brings him within the purview of our series, and I must say, his cast bronze animals are breathtakingly lovely, as we see in his group of three bears of 1932 (second image), or his relief of a puma chasing two deer, from 1916 (third image).

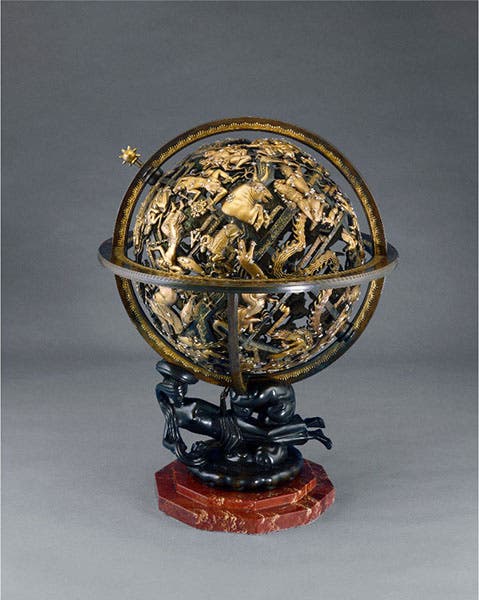

But Manship also made a celestial globe – several of them, in fact – which makes him almost unique among artists. Of the hundreds of celestial globes that have been fashioned over the centuries, almost all have been printed or drawn. I know of only one other that was sculpted, and that is the globe being held by Atlas in the Farnese Atlas, made around 300 B.C.E., and now in Naples, which you can see here. Manship made his first star globe in 1934, which I have seen in person, at the Saint Louis Museum of Art. It is small, about 25 inches tall, and it is just gorgeous, as you can appreciate in the detail that introduces this post. Apparently, Manship cast each of the constellation figures separately, along with labels, and hundreds of stars, and then put them in place individually on the globe framework. Its beauty derives principally from the constellation figures, which Manship drew from ancient Greek, Indian, and Asian art. I know of four of these globes, and there are probably more; our images come from the one in the Saint Louis Art Museum (fourth and first images).

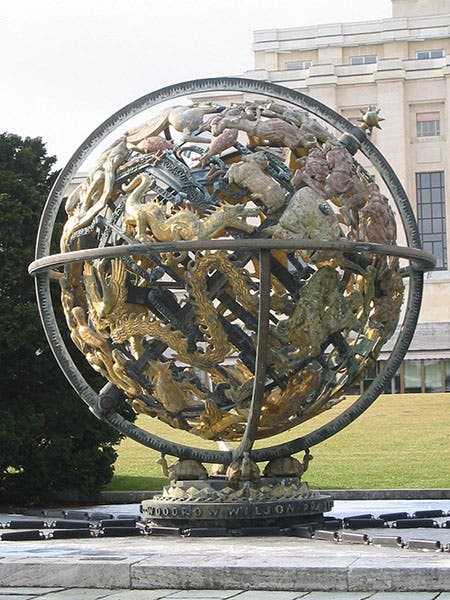

Manship also made one king-sized celestial globe, which the Fates have not been kind to. In 1936, the Woodrow Wilson Foundation commissioned a memorial for Wilson from Manship. He decided that a large version of his celestial sphere, containing constellations whose origins lie in Greek, Egyptian, Persian, Indian, and Chinese mythology, would be an appropriate symbol of world peace and brotherhood. When he completed the design in 1938, the molds were sent off to Bruno Bearzi in Florence, who cast them using a special bronze alloy. Each of the 85 constellations was cast separately, and gilded, and then silver stars in different sizes were applied in the right places on the constellation figures. The resulting sphere, which was installed in front of the Palace of Nations in Geneva in 1939, was over 13 feet across. It even had a motor installed, designed to rotate the sphere in sync with the earth. This was a monumental achievement, the first accurate large-scale celestial globe ever. It is now the property of the United Nations.

The sphere is still in place, as you can see in the photographs; we show the entire structure (fifth image, above), and a detail of the bottom part of the sphere, showing the constellations of Pavo the peacock, Indus the Indian, the Phoenix, the Toucan, and Hydra the water snake (sixth image, just above). But all is not well with the sphere; many of the figures have cracked and corroded, and the base itself (which charmingly sits on four turtles!) has large fissures, threatening to collapse the sphere. The motor has not worked since the 1940s. The United Nations apparently is not allowed to spend money on itself, so various foundations are trying to step in and save the sphere. Here is the website of one of them, which has additional pictures of the sphere and its state of disrepair, and a photograph of two of the constellations, Lyra the Lyre before restoration, and Cygnus the Swan, after restoration. The restoration project has been going on for over 20 years, without much progress, it seems; one hopes that it picks up steam and pace, before the sphere topples from its foundation. It is not a good thing when symbols of international harmony and brotherhood are allowed to fall apart.

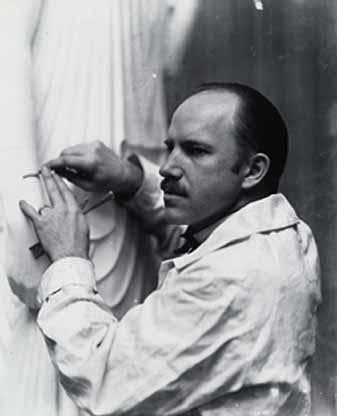

The Smithsonian Museum of American Art has a substantial collection of Manship art and drawings, and several portraits, one of him at work in his studio, which we show here, and a self-portrait of a much younger Manship. I could not find any indication that SMAA owns a small Manship celestial globe. One sold for auction at Sotheby's in 2006, for just under a million dollars. I imagine our Library will not be acquiring one anytime soon.

As an end note, since we mentioned Bruno Bearzi as the foundry craftsman who cast the pieces for the Woodrow Wilson globe in Geneva, we might comment that the Linda Hall Library has its own connection with Bearzi, as he cast the six exterior bronze panels that originally adorned the Library’s west exterior (four are still in place; two have been moved inside). You may see these handsome panels, and read about them, in our post on Bearzi.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.