Scientist of the Day - Paul Kane

Paul Kane, a Canadian painter, was born Sep. 3, 1810, in Ireland. He moved with his family when he was 9 years old to York (now Toronto), and thereafter considered himself a Canadian. He took some painting lessons and earned his living for a decade as a furniture painter and a portrait artist, in Canada and the northern U.S. He spent a few years in Europe, mostly Italy, taking some further art lessons but mostly teaching himself by copying paintings in Rome and Florence. In 1842, just before he returned home, Kane met George Catlin in England. Catlin had just completed a large set of paintings of North American Indians and was trying to market them, and Kane got the idea of doing for the people of the First Nations of central and western Canada, what Catlin had done for the Plains Indians of the American Midwest.

Kane made one short trip to Lake Huron in 1845, and with his sketches, he was able to enlist the support of George Simpson, head of the Hudson's Bay Company. Simpson gave Kane papers that allowed him to travel with the fur canoes and stay in company forts. So Kane make a second, much more extensive trip from 1846 to 1848, travelling entirely across Canada and down the Columbia River to the Pacific, staying at Fort Vancouver and Fort Victoria, and making sketches all the way. He then returned to Toronto and began turning his sketches into finished paintings.

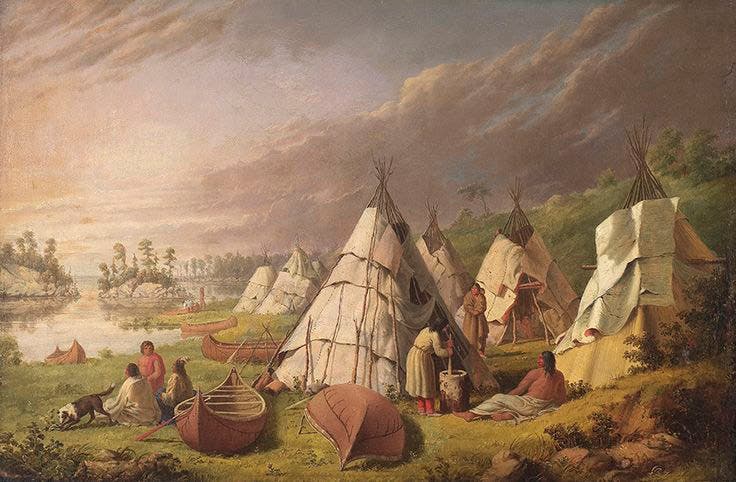

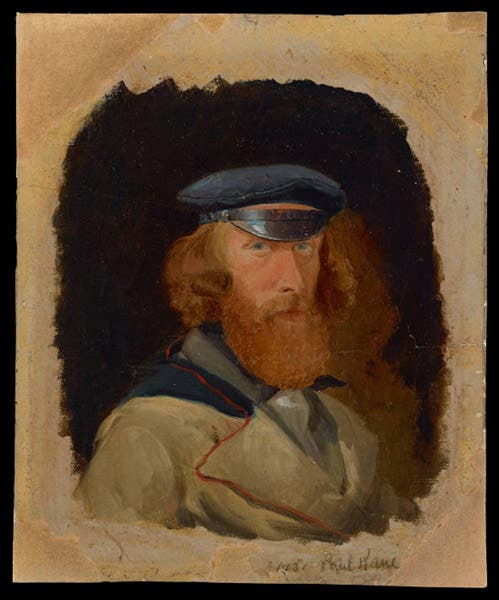

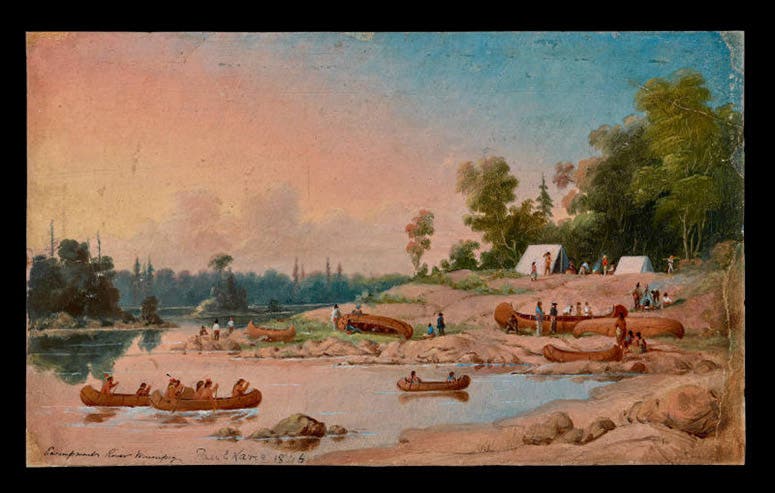

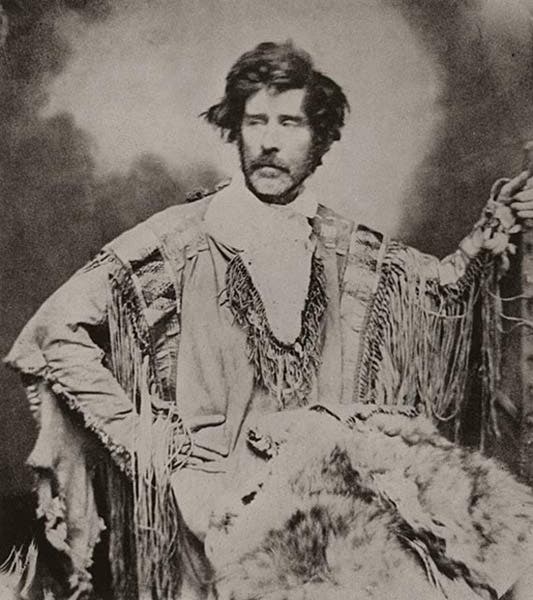

Kane's real genius lay in the sketches, in pen, watercolor, and oil, on paper. There are over 700 of them that survive. They capture many moments and places that disappeared soon after Kane went through, and his drawings of First Nations and Métis encampments and hunts are captivating in their realism. Experts say the details of native dress and lifestyle are meticulous and accurate. Most of the sketches can now be found in the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto and the Stark Museum of Art in Orange, Texas. We show two of those here (third and fourth images), as well as a sketch he made of himself (second image).

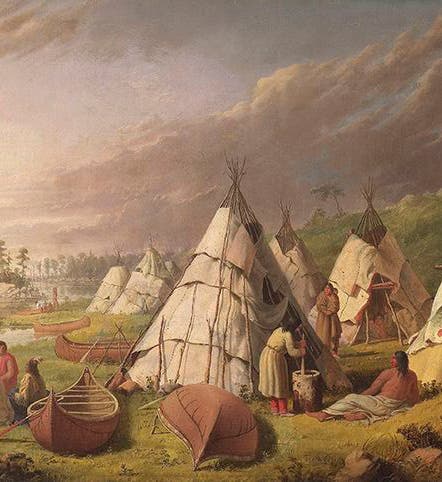

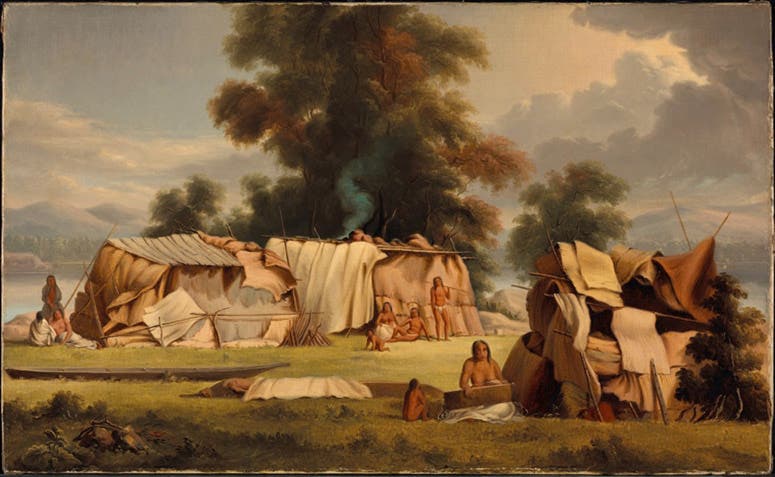

But Kane didn’t make any money from his sketches, and he needed an income. So he used his sketches to fashion oil paintings that would appeal to the market, and here he relaxed his standards. He changed features, invented scenes, and imposed a European classicism on his Canadian subjects. He probably had to, since the paintings were for paying customers who could pretty much determine what they wanted in a western painting. But he was successful. He attracted one patron who commissioned 100 oil paintings for a handsome sum; these were later bought by another collector and are now in the Royal Ontario Museum. Ethnologists find the paintings less valuable than the sketches, since many of the scenes are invented, but they can be fairly stunning, nevertheless. One of his most famous paintings, and one of his earliest, sketched at Lake Huron in 1845 and painted after 1848, was commemorated by a Canadian postage stamp in 1971 (sixth image). We also link to the painting, now in the Royal Ontario Museum, that was made from his sketch of canoes on the Winnipeg River (fourth image), and is fairly faithful to the original sketch; this image can be greatly enlarged.

Kane lived out the rest of his life in Toronto and did so successfully; he was one of the very first Canadian artists to earn a living from his vocation. In addition to his self-portrait (second image), there are several surviving photographs of this rugged voyageur painter, and we include one of those as well (seventh image).

Kane lost his eyesight in his later years and was unable to continue painting. He died in 1871, and is buried at the St. James Cemetery in Toronto.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.