Scientist of the Day - Paolo Sarpi

Paolo Sarpi, a Venetian cleric, political advisor, and scientist, died on Jan. 15, 1623, at the age of 70. He joined the Servite order at age 14, probably because one of his early tutors was a Servite friar. The Servites were a mendicant order, almost as old as the other mendicant orders, the Dominicans and Franciscans, if not quite so well known. From 1588 on, Sarpi lived in the Servite convent at the church of Santa Maria dei Servi in Venice, the third largest church in that city, which was unfortunately dismantled on the orders of Napoleon in the early 19th century, and little remains except a chapel and several gateways (second image).

In scientific circles, Sarpi is best known for his role in aiding Galileo’s early work with the telescope. It had long been thought that Galileo heard about the Dutch invention of a spyglass in 1609 and figured out how to build one pretty much on his own. It now appears that Sarpi received an actual Dutch telescope in July of 1609 and that Galileo may have seen that telescope and how its lenses were placed before embarking on his own construction, which was noticeably better than the Dutch version. When a Dutch telescope was offered for a tidy sum to the Venetian Senate in August of 1609, Sarpi told them to hold off, because Galileo would soon have a better one to give them.

Sarpi was in a position to make recommendations to the Venetian Senate because he had become the principal theological and political advisor to the Senate. He had spent some time in Rome as a Venetian emissary, when Rome was giving Venice problems, and had shown himself to be both learned and astute. He had also demonstrated an extensive scientific knowledge of the physics of motion, magnetism (he greatly admired William Gilbert’s 1600 book, De magnete), the anatomy and physiology of the heart, and he had a reputation for being a skilled mathematician, all unusual traits for a Servite friar.

Sarpi is best known for an episode that had nothing to do with science or Galileo; he guided Venice through a difficult period in 1606-07, when Pope Paul V set Venice under an Interdict for putting two Catholic priests on trial in a civil court. Venetian clergy were forbidden by the Pope from holding services, but the Senate, on Sarpi’s advice, blithely ignored the Pope and directed its priests to carry on as usual, and when the Jesuits resisted, they were sent packing from the city. The Interdict failed, to the great embarrassment of the Papacy, and was lifted, and Sarpi was the hero of the hour.

Sarpi did not like the Papacy as an institution, feeling that it often abused its power, and in 1619, he published his major written work, a History of the Council of Trent, that series of synods begun in 1540 when the Catholic Church established the basic tenets of the Counter-Reformation. Sarpi felt that the Papacy had not tried to deal with the charges of clerical abuse raised by Martin Luther and other Protestants, but instead worked to exacerbate them.

Sarpi was an unusual cleric. He has even been suspected by one historian of being an atheist, which would make him even more unusual. He was certainly anti-Papacy. But in his forays in the realm of science, he was clever and perspicacious, appropriately for someone involved in the introduction of the telescope into astronomy. It is too bad that Galileo left Sarpi and the Venetian Republic for Florence in 1610, leading to a souring of their relationship. Perhaps, had Galileo stayed at Padua, Sarpi might have decided to write a history of the Copernican Revolution, instead of taking on the Council of Trent.

After Sarpi’s death in 1623, he was buried in the cemetery at Santa Maria dei Servi. When that chuch was destroyed and dispersed, his remains were moved to the cemetery of San Michele on an island in the Lagoon of Venice (fifth image). I do not believe the whereabouts of his grave is known. In 1892, a statue was erected in his honor in the Campo Santa Fosca in Venice, not far from the church where he lived for most of his adult life (fourth image).

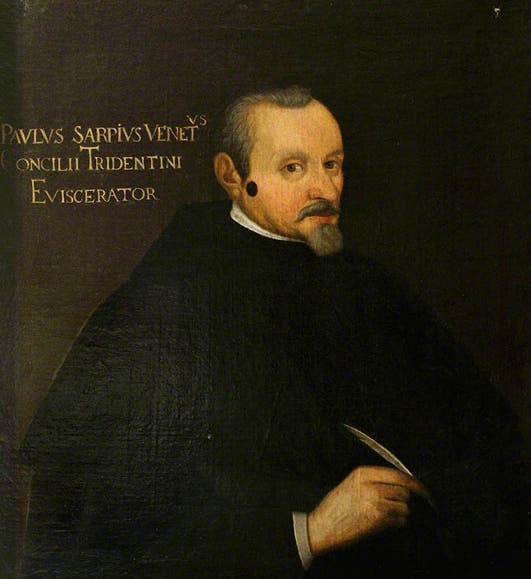

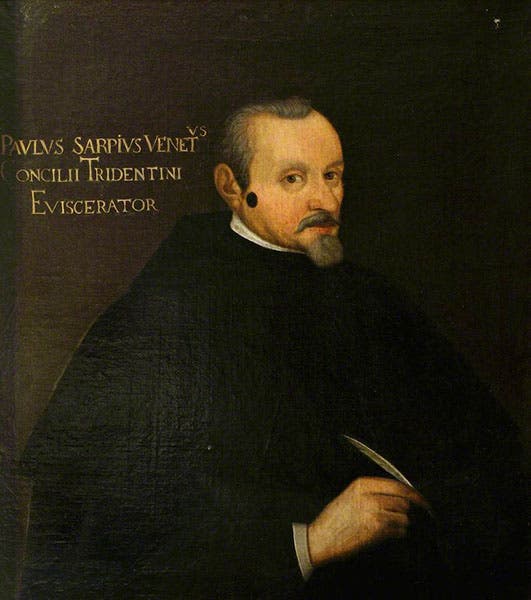

There are two contemporary or near contemporary portraits of Sarpi, one at the Bodleian Library at Oxford (first image), the second at Ham House in Richmond, now part of the National Trust (third image). Clearly one was copied from the other, but I do not know which was the original – I am guessing the Bodleian copy was first. Following the example of the issues of the first edition of Isaac Newton’s Principia, we might refer to the two portraits as the “two-line” and the “three-line” Sarpi portraits. In both, he is identified, dramatically, as the “eviscerator” of the Council of Trent.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.