Scientist of the Day - Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso, a Spanish painter, died Apr. 8, 1973, at the age of 91. He divided his working life between Paris and Barcelona. His work rarely had anything to do with science, even though it is sometimes said that his cubism was inspired by Albert Einstein's special relativity; this is simply not the case.

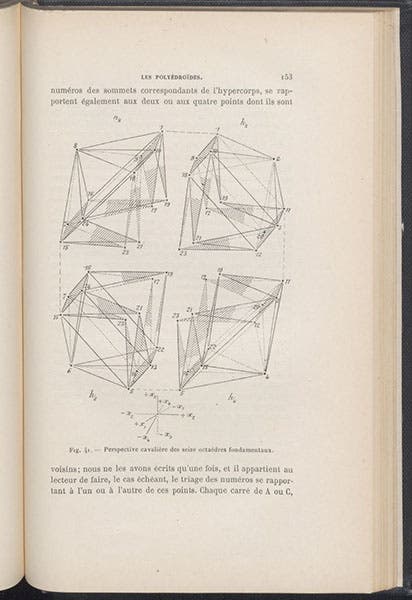

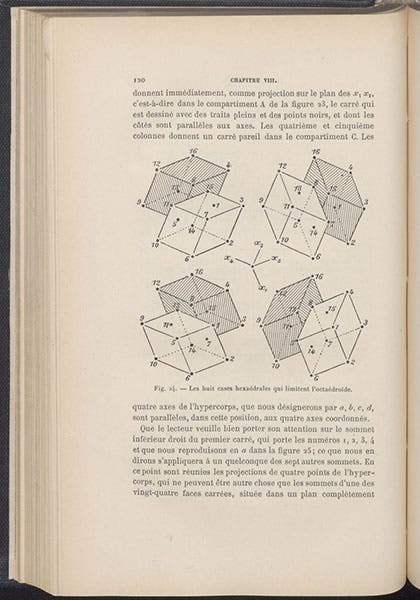

But it has been argued, and I think convincingly, that an early form of Picasso’s cubism, called analytic cubism (1909-1912), was profoundly influenced by a scientific book – it just wasn't Einstein’s. It was a book published in 1903 by Esprit Jouffret, a French mathematician, and it was called Traité élémentaire de géométrie ą quatre dimensions (Elementary Treatise on the Geometry of Four Dimensions). The book examined how four-dimensional objects appear when projected onto three-dimensional space. For example, a cube in three-dimensional space has six faces, each one a square; a hypercube, in four-dimensional space, has eight “cells,” as a three-dimensional face is called, each one a cube. How does a hypercube look to an observer confined to three dimensions? Or a hyperoctahedron? Or any other of the six regular four-dimensional polyhedrons? Jouffret discussed and illustrated this four-dimensional projective geometry in his book. Even if you can’t follow the math, it is hard not to be enticed by the illustrations (third and sixth images).

Sometime before 1983, Linda Henderson, an American art historian, noticed a striking resemblance between some of Jouffret’s diagrams and a painting by Pablo Picasso, A Portrait of Ambroise Vollard, completed in the spring of 1910 (fifth image). Many before had noticed the geometric nature of cubism – it would be hard not to. But Henderson went further, discovering that Picasso had been introduced to Jouffret’s book by a mathematician in his entourage, Maurice Princet, and that Picasso had actually read the book and had been inspired by it to break down the face of Ambroise Vollard into Jouffret’s exploded octahedral faces. Henderson’s book was called: The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art (1983).

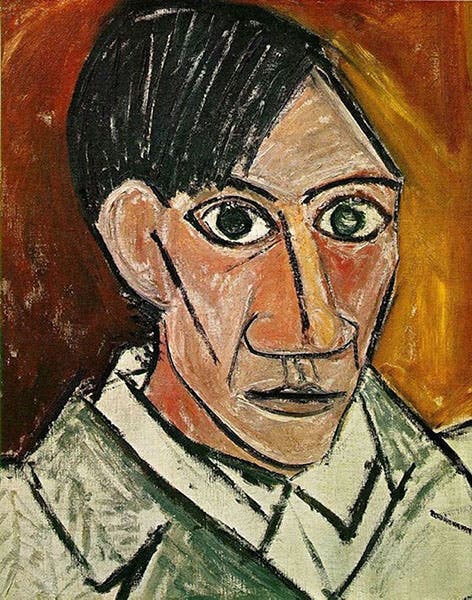

Henderson then considered a painting that Picasso completed six months later, Portrait of Henry Kahnweiler (1910; first image), in which the image was geometrically broken down in a slightly different manner. She found the inspiration for this elsewhere in Jouffret’s book.

In the years since, Henderson’s conclusions about Jouffret’s importance for Picasso’s analytic cubism seem to have been generally accepted by art historians. A more recent book by Tony Robbin, Shadows of Reality: The Fourth Dimension in Relativity, Cubism, and Modern Thought (2006) gave a full stamp of approval to Henderson’s scholarship. I am not qualified to judge myself, but I hope Henderson and Robbin are right in arguing that Picasso was influenced by a book on four-dimensional geometry. True interactions between science and art are not as common as you might think; it is nice to have this one added to the stable.

I wrote a post on Jouffret four years ago, which told essentially the same story. I wanted to tell it again, because an essay on projective geometry can easily lose most of its readers long before they get to the Picasso connection. I thought if I told it again, with Picasso as the lead, it might attract an additional readership. Just to add something new, I include a third Picasso painting, from 1911, that I think might also reflect the influence of Jouffret (seventh image). It is The Poet, in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice. We have no Picassos in our library, but we do have Jouffret’s book in our History of Science Collection, and you can also digitally leaf through it online.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.