Scientist of the Day - Orson Welles and H.G. Wells

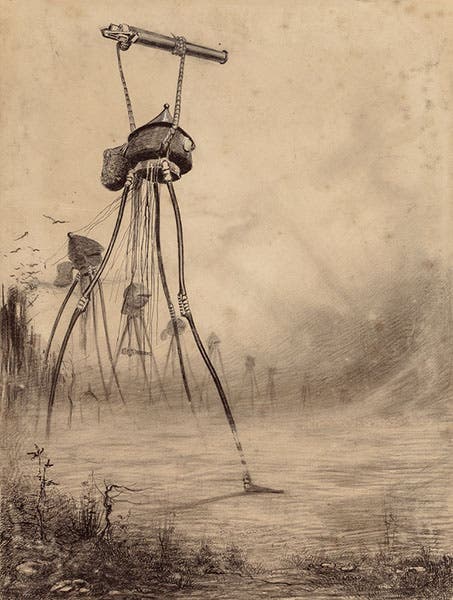

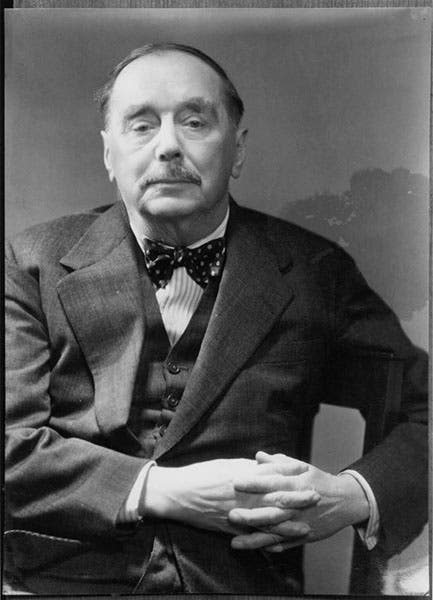

On Oct. 30, 1938, the Mercury Theatre on the Air went on the air with a broadcast called "The War of the Worlds." The show was the brainchild of Orson Wells, based on the 1898 novel by his near namesake, H.G. Wells (second image). Everyone knows the story – how Welles and his cohorts presented the tale of the Martian invasion as a live news broadcast, as if aliens at that moment (8:00 PM) were landing at Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, and deploying their army of gigantic tripods throughout the countryside. Everyone also knows that widespread panic ensued among the listening public, who fled into the streets by the thousands. Or so the newspapers of the next day reported (third image).

It turns out that this part of the story is not so true. The headlines were real, but not the facts that supposedly lay behind them. There were certainly many listeners who thought the show was reporting real events, and Welles had to answer to a bevy of inquiring reporters the next day who wondered whether the deception was intentional. But public hysteria? Several recent investigations have failed to turn up any sign of widespread panic, or really panic of any kind. It is possible to conclude that newspaper owners and editors deliberately played up the irresponsibility of radio broadcasters who intentionally deceived the public, in order to discredit this new medium, radio, that was already threatening the news monopoly of the printed newspaper. It also turns out that hardly anyone listened to the Mercury Theater on the Air – less than 1% of the radio audience – so 99% of the listening population didn't even know what was happening, nor did the even larger population who didn't listen to radio at all.

Nevertheless, the unincorporated community of Grover's Mill is proud of its choice as landing site for the purported Martian invasion, and in 1988, the not-quite-a-town erected a monument to both the Martians and the broadcast. It is quite handsome, eight feet tall, fashioned of bronze, with an image on its face of an alien saucer, Orson Welles at the microphone (compare to our fourth image) and a terrified family sitting around their radio. Whether it has increased the influx of tourists to Grover's Mill we do not know. But the monument did find a place in Atlas Obscura.

The 1938 broadcast played a pivotal role in the 1984 film, The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai, which builds on the premise that the 1938 invasion was not a hoax, and Martians really did land that day, adopt humanoid bodies, and register with Social Security under names such as John Small Berries, John Ya Ya, and John Bigbooté. It just so happens that we featured Buckaroo Banzai as our Scientist of the Day not so long ago, if you would like to pursue this thread. One final note – Welles’ broadcast is often described as a Halloween hoax. In fact, it was aired the day before Halloween, Oct. 30, not Oct. 31, which is why we are celebrating it today and not on Halloween. But if you were under that misimpression, don’t feel bad – Jeff Goldblum got it wrong as well in The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai.

One final question: Did H.G. Wells make any comment about the broadcast based on his book? He was still very much alive at the time, and the photo here was taken one year later, in 1939. Presumably that question has been answered, but we didn’t run across it while researching this essay. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.