Scientist of the Day - Nicolaus Steno

On Oct. 23, 1988, Pope Paul II beatified the Italian geologist Nicolaus Steno, declaring him Blessed. This was the third step in a four-step process that could lead to Steno’s canonization as a Saint in the Catholic Church.

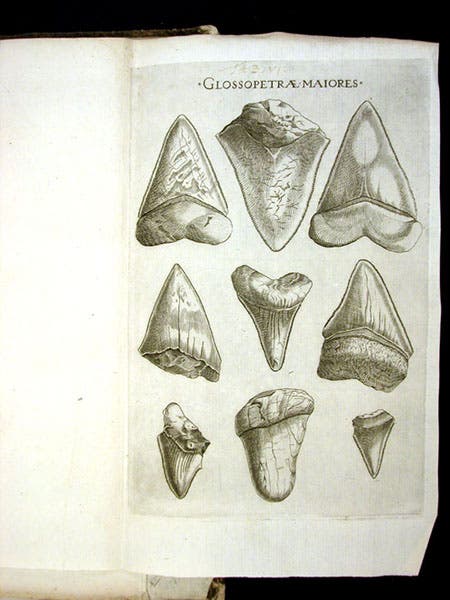

Steno is not well known as a religious figure. He is not even well known as a scientist, although his insights were arguably as great as those of his near contemporaries, Galileo and Newton. Steno was born in Denmark in 1638 and studied medicine in Copenhagen before heading out on his version of a grand tour, with stops in Paris and Italy. It was in Florence in 1667, where the Cimento Academy, one of the world's first scientific academies, was folding up its tent, but where the Medici family was still interested in patronizing natural philosophers, that Steno's scientific flame burned brightest. He first came to realize that tonguestones, those figured stones that look like giant sharks' teeth (second image), were in fact once in the mouths of sharks, and that he could prove it. The theory of the organic origin of fossils really began with Steno. Then he proceeded to discover the basic principles of stratigraphy, the laws that determine how sediments build up over time to produce stratified rocks, and how one could read the strata to determine the geological history of a location, such as the Arno River valley where Florence was situated. Steno was at once the father of paleontology and historical geology, and his two books on the subjects, published in 1667 and 1669, are both milestone publications of the scientific revolution of the 17th century. We wrote a post on Steno some 8 years ago, in which we, too briefly, made the case for his scientific genius, but the images we showed, although uncaptiond, are still excellent, and include a splendid oil portrait of the young Steno.

We did not mention in our first post that there are in fact three Steno publications on geology, the third being a translation of his 1669 Prodromus by Henry Oldenburg, Secretary of the Royal Society of London. This third volume is much scarcer than either of the better-known works, and we are happy to have it in our collections. We show here the title page, and a detail of the plate depicting schematically the deposition and erosion of the strata around Florence (third and fourth images).

The odd thing about Steno (odd, at least to those who see scientific inquiry as a worthwhile pursuit), is that he no sooner rose to a pinnacle of scientific accomplishment than he went down the other side and gave up science almost completely. Steno, like most Danes, had been raised as a Lutheran, but when he arrived in Italy, he met Pope Alexander VII and found himself strongly attracted to the rituals of Catholicism. In 1667, at the same time he was publishing his treatise on fossilized sharks teeth, he converted to Roman Catholicism. After his Prodromus came out in 1669, he returned to Denmark and visited the Netherlands, and then came back to Florence to tutor the Medici family children. His interest in anatomy and geology were fading, and now he was interested in the care of souls. He was ordained as a priest in 1675, and two years later, he was appointed Vicar Apostolic for the Nordic Missions, and consecrated as a bishop, the "Titular Bishop of Titiopolis." Pope Innocent XI sent him into the Lutheran den of Hannover to bring Protestants back into the fold, and then he was transferred to Hamburg in 1683. In Hamburg, he became more and more ascetic, giving up all his possessions to feed the poor, and his asceticism continued when he moved to Schwerin. He ate only bread and grew dangerously emaciated. He was better received in Schwerin than in Hannover and Hamburg, but his physical condition worsened, and he finally died there, probably of malnutrition, on Nov. 25, 1686. He was just 48 years old.

Steno's remains were shipped to Florence, at the request of Duke Cosimo III de Medici, and he was laid to rest in the basilica of San Lorenzo, where many of the Medicis are buried. Interest in canonizing Steno began to build in the 1920s. Sometime before 1953, his body was disinterred and transferred to a beautiful ancient sarcophagus that had been fished out of the Arno River and acquired by the Italian government, which donated it to San Lorenzo for the purpose of providing a new resting place for Steno. And then came the beatification, on this day in 1988. Ordinarily, evidence of a miracle is necessary for beatification, although apparently that can be waived, and evidence of another is required for canonization, where I don't think it is an optional requirement. I do not know what miracles, if any, are credited to Steno, because I could not find any documents associated with his beatification on the internet. If any reader knows where I might find that information, I would be grateful.

Scientists are usually taken aback when they learn that Steno turned natural science upside down in just three years, 1666-69, and then gave it all up for religious pursuits. But who are we to say how a person should live his or her life? Steno lived the life he chose, and he was not afraid to alter course when the life he was living proved unfulfilling. We should be grateful for the three years he did devote to geology, and wish him posthumous luck on his road to sainthood. If he is ultimately canonized, he will be the first accomplished scientist since Albertus Magnus to achieve that status (although he will be the second Saint Nick to do so).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Title page, Prodromus to a Dissertation Concerning Solids Naturally Contained within Solids, by Nicolaus Steno, transl. by H.O. [Henry Oldenburg], 1671 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/401815b2-238e-4ff1-acdf-79e68999ad3c/steno3.jpg?w=394&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![The stages of the deposition and erosion of strata, Arno River valley, detail of an engraving in Prodromus to a Dissertation Concerning Solids Naturally Contained within Solids, by Nicolaus Steno, transl. by H.O. [Henry Oldenburg], 1671 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/4c7b74cc-5ebc-40b9-b7c9-8f6a660b526e/steno4.jpg?w=800&h=373&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)