Scientist of the Day - Niccolo Zucchi

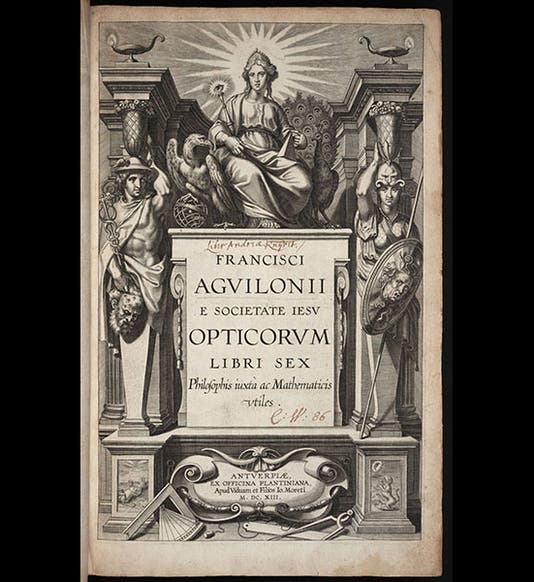

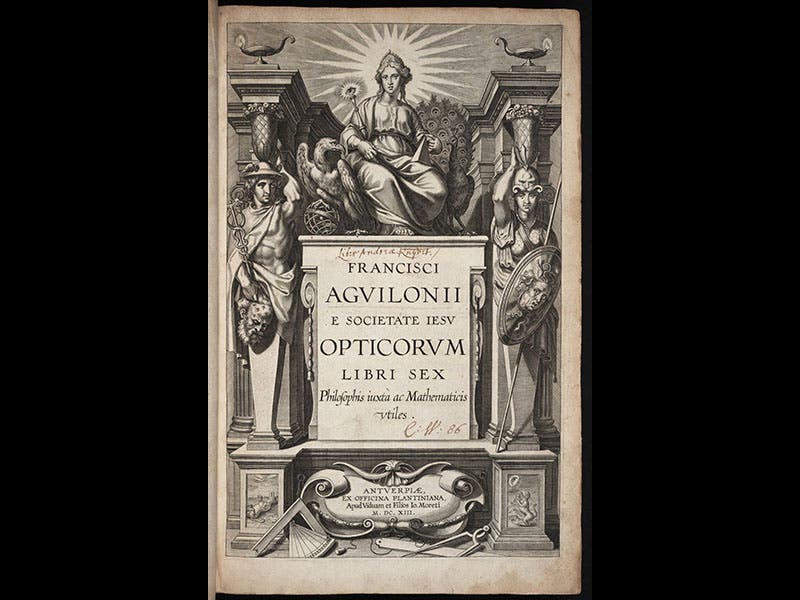

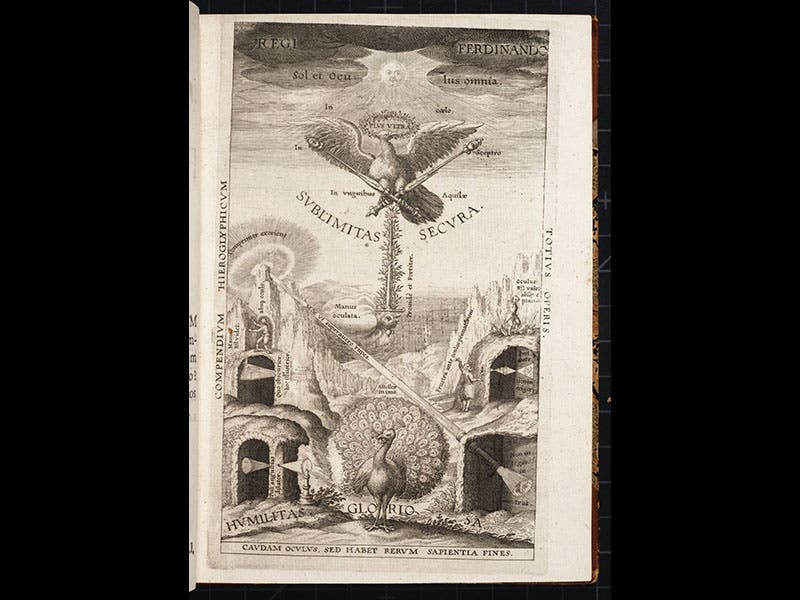

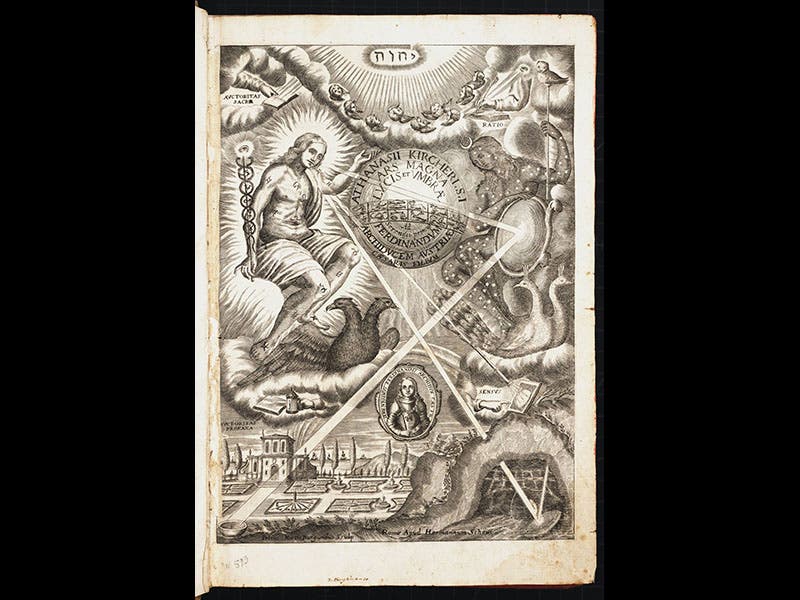

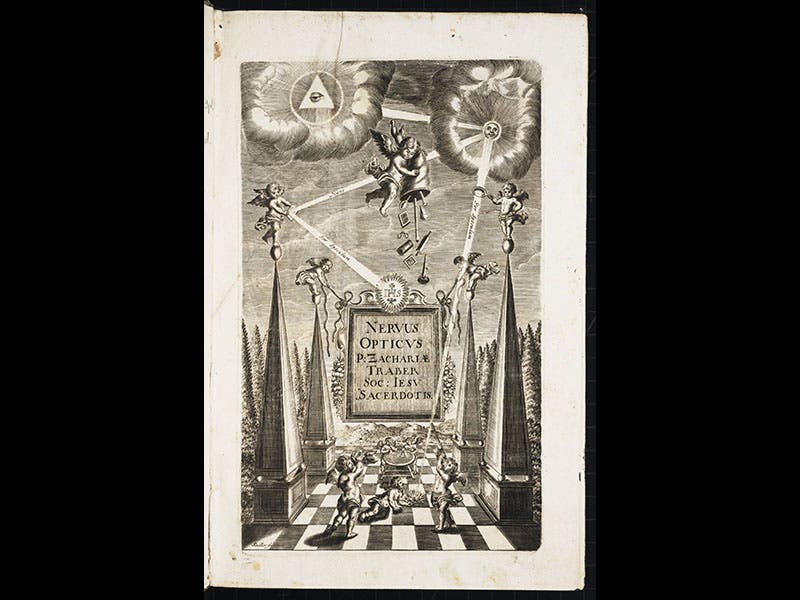

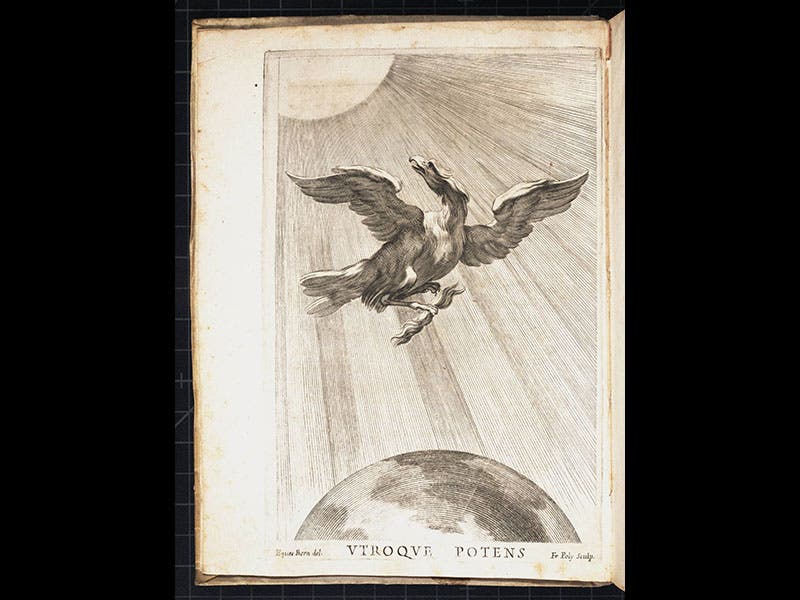

Niccolo Zucchi, an Italian Jesuit physicist, died May 21, 1670, at age 83. Zucchi is known, although just barely, for being the first to see the belts of Jupiter with a telescope in 1630, and for possibly making the first reflecting telescope, although most authorities reject this latter claim as improbable. But in 1652, Zucchi published the first volume of his Optica philosophia, and it contained an allegorical frontispiece, and although Zucchi had nothing to do with it, today he is going to bask in its light, since it is one of the finest emblematic engravings that the science of optics has ever produced. It seems appropriate to sneak up on this illustration, so the first four images above are emblematic illustrations—title pages or frontispieces—from four other works on optics published in the 17th century: Francois Aguilon’s Opticorum (1613, first image above); Christoph Scheiner’s Oculus (1619, second image); Athanasius Kircher’s Ars magna lucis et umbra (1646, third image), and Zacharias Traber’s Nervus opticus (1675, fourth image). Interestingly, all four authors, like Zucchi, were Jesuits. Although we don’t have time or space to analyze any of these four here, each is clever, rich in allusion, studded with references to debates about scientific method, but, for all the erudition on display, somehow lacking in style and drama. Zucchi’s frontispiece (fifth image) is something completely different—very simple, yet elegantly powerful, showing an eagle turned toward the sun, with a two-word motto at the bottom: Utroque potens, “powerful in both worlds”. The reason for the difference is that Zucchi's frontispiece was designed by a true artistic genius, Gianlorenzo Bernini, the Roman sculptor and painter. For his design, Bernini drew upon an ancient eulogy by Claudian about his emperor, Honorius, which explained that young eagles (like young emperors) are tested by being made to soar aloft and look directly at the sun. Those that cannot bear the light will perish, but those that can stand the sun's power will become monarchs of the air and will inherit the thunderbolt of Zeus. Since Zucchi dedicated his book to his emperor, Ferdinand II (a Habsburg, whose emblem was an eagle), the raptor does double-duty here, suggesting that Ferdinand too is "powerful in both worlds." This is the only book illustration that Bernini ever did, and it makes us at once rejoice, and regret that he never ventured another. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.