Scientist of the Day - Nettie Maria Stevens

Nettie Maria Stevens, an American cell biologist and geneticist, was born July 7, 1861, in Vermont. She studied science for several summers in Martha's Vineyard, and then taught school for 7 years until she had enough money to enroll at Stanford University in 1896. She studied biology, receiving a B.A. and an M.A. by 1901, at which time she enrolled in the PhD program at Bryn Mawr College. This was just one year after the work of Gregor Mendel had been rediscovered independently by three investigators, after 35 years of neglect, so it was an exciting time to work in genetics. And it just so happened that one of the biology professors at Bryn Mawr was Thomas Hunt Morgan, who would later move to Columbia University and formulate the chromosome theory of inheritance.

Ms Stevens received her PhD in 1903, which was an impressive feat for any woman pursuing a career in science at that time, and she published more than half-a-dozen papers even before she had her degree in hand. She received fellowships for postgraduate study in Germany, and at the renowned Naples Zoological Station. And then she was awarded a prestigious grant from the Carnegie Institution of Washington for 1903-04, during which time she made her important discoveries about the determination of sex in organisms.

The prevailing view, once Mendel's laws had been absorbed, was that while genes may play a role in sex determination, the sex of an organism is not determined at the time of fertilization, but later, and gradually, by the environment is which the embryo develops. Stevens’ plan was to observe the chromosomes in the germ cells of several kinds of insects and compare their visible chromosome makeup with the sex of the fertilized embryo. Not all the chromosomes in a cell look alike; they have different sizes and shapes. Perhaps one or two of the 20-odd chromosomes in most insect species played a role in determining sex. Stevens had indifferent results with aphids, but when she looked at the germ cells of Tenebrio, a meal worm, she noticed something interesting. The somatic cells (which produce the eggs) of female mealworms have 20 large chromosomes, while the somatic cells of males have 19 large and one small chromosome. Half of the sperm cells have the small chromosome; half do not. If a sperm with the small chromosome fertilizes an egg, the embryo is always male. Further experimentation led Stevens to propose, in a monograph published in 1905 by the Carnegie Institution, that the small chromosome (the Y chromosome, as it is now called), if present in the fertilized embryo, determines that the organism will be male; its absence (or rather, its replacement by the larger X chromosome) determines that the embryo will be female. The environment of the developing embryo has no effect; sex is fully determined at the moment of fertilization, by the absence or presence of the Y chromosome.

The credit for the discovery of the Y chromosome and its significance in sex determination is complicated by the fact that the same discovery was made about the same time by another biologist, Edmund B. Wilson. Wilson was an older and much more prominent investigator, and a good friend of Morgan, and he lived a lot longer than Stevens. So until recently, credit for the discovery of the sex chromosomes often went either to Wilson, or to Morgan, who incorporated it into his milestone 1915 book on the chromosome theory of inheritance. Sometimes Stevens was mentioned along with Wilson and Morgan, but sometimes she was not. And the fact that she died of breast cancer in 1912, at age 50, when her career had really only just begun, meant that she could not speak up for herself as the chromosome theory became established.

However, modern historians of genetics have discovered documents that demonstrate that Wilson did not really formulate the correct theory until after he saw Stevens’ paper in 1905; even though his paper was submitted first, it was later revised in proof, after Stevens’ paper appeared. Moreover, Wilson did not discard the possibility of environmental determination of sex until later. Morgan at the time didn’t even accept the idea that chromosomes were home to the genetic material – his conversion came much later. So Stevens really deserves the lion's share of the credit for discovering the X-Y chromosomes and for understanding their role in sex determination. And she is now, finally, getting that credit.

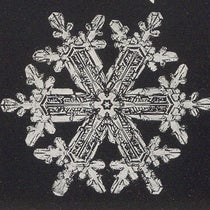

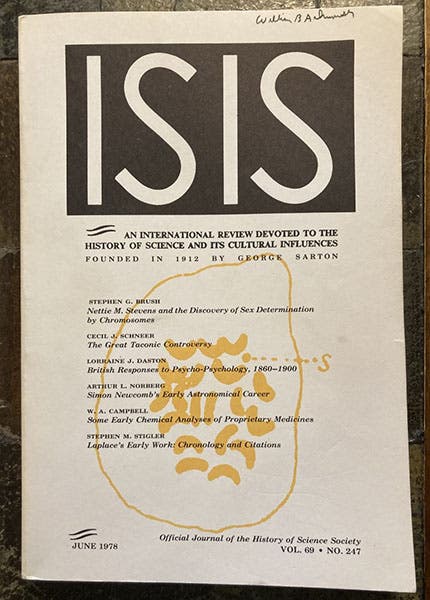

Chromosomes of Tenebrio, with the Y chromosome indicated by the letter “S”, from the 1905 paper of Nettie Maria Stevens, reproduced on the cover of Isis, vol. 69, no. 247, 1978 (author’s collection)

Stevens’ monograph of 1905, titled Studies in Spermatogenesis with Especial Reference to the ‘Accessory Chromosome’, appeared as a Publication of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, which we do not have in our Library, a very curious lacuna in our collections. So we show you instead the front cover of the June 1978 issue of Isis, the history of science journal, which contains a paper by Stephen Brush that began the rehabilitation of Stevens. The cover is printed over an orange background image, which was taken from Stevens 1905 paper, and shows the chromosomes of Tenebrio. You can see 19 rather prominent chromosomes, and then the tiny Y chromosome at upper right, identified by the letter S (second image).

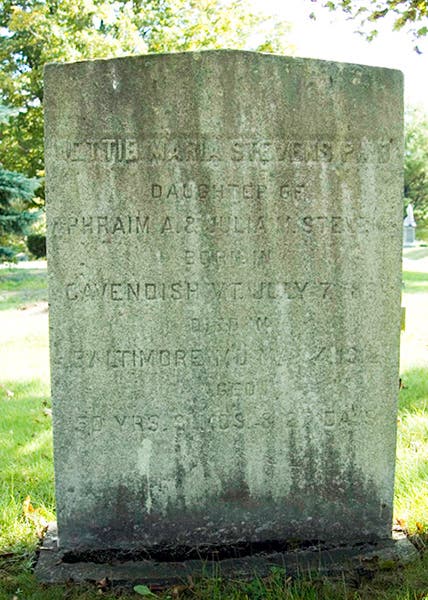

Nettie Stevens stayed at Bryn Mawr for her entire brief career, passing away on May 4, 1912. Thomas Hunt Morgan wrote a respectful and appreciative obituary notice for the journal Science in Oct. 1912. Stevens was buried in Fairview Cemetery in Westford, Mass., where she shares a plot with her mother and father and three siblings (third image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.