Scientist of the Day - Nathaniel Palmer

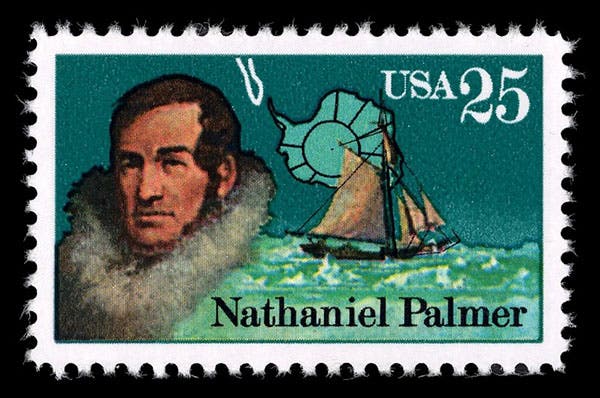

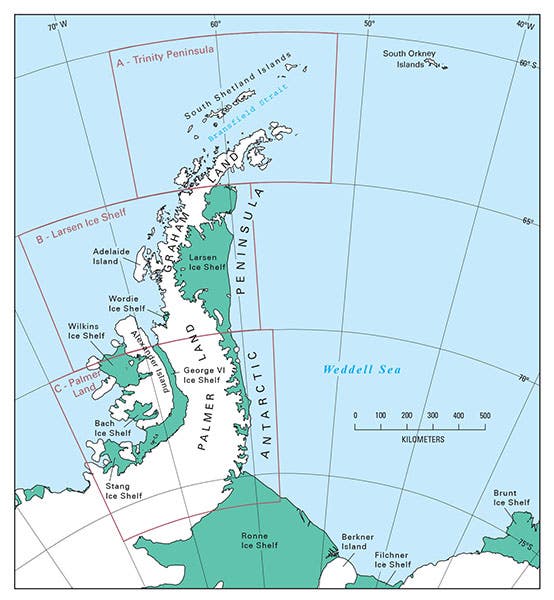

Nathaniel B. Palmer, an American sealer, sailor, and ship captain, died June 21, 1877, at the age of 77. Palmer was raised in Connecticut, son of a boatbuilder, and he went to sea at a young age, as did many who grew up in that land of seafarers. In his late teens, he took part in sealing expeditions to the waters around the yet-undiscovered continent of Antarctica. When he was just 21 years old, he received command of his own ship, a petite sloop called Hero, and on Nov. 17, 1820, he and his small crew became the first Americans to sight the Antarctic continent. This was just 10 months after Antarctica was first glimpsed by the Russian explorer Fabian Bellingshausen (unbeknownst to Palmer – in fact, unbeknownst to anyone for many years). The area Palmer visited, that long finger of land that sticks up from Antarctica toward South America, was for a while called Palmer's Land. However, the British claimed they discovered the area, and took to calling it Graham Land, after their first Lord of the Admiralty. Nowadays, thanks to the miracle of treaty negotiations (1964), we now call the entire finger the Antarctica Peninsula, and this in turn is divided into Graham Land (the end of the finger) and Palmer Land (the base of the finger; see map, second image).

Palmer is often described as the first to sight Antarctica (which is not true) or the first American to see Antarctica (which may be true – since he did not land, it is hard to know exactly what he saw. After all, an Englishman, John Ross, two years earlier, had claimed to see an entire mountain range at the top of Baffin Bay, closing off what was called Lancaster Sound, and the next year, two ships sailed right through the imaginary mountains and into the Arctic archipelago). But Palmer later showed that he was very good at nautical matters, so perhaps in this case, he can be believed.

By the 1840s, Palmer had given up sealing and had moved into shipping. In 1843, he took command of a sailing ship called the Paul Jones and took her from Boston to Hong Kong in 111 days. This was just before the first clipper ships went into production; indeed, Palmer is often credited with having helped come up with the basic clipper-ship hull design, based on his considerable experience with long-distance sailing. In his honor, a clipper ship was launched in 1851 with the name N. B. Palmer, and on its first long voyage, it cut at least 30 days off the run to Shanghai. A model of the N. B. Palmer was displayed at the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London in 1851, and it supposedly attracted a great deal of attention and admiration. Perhaps the painting we show (third image) was made from such a model, since as far as I know, the N. B. Palmer did not make it into the late 20th century, when this painting was executed.

Palmer made enough money at shipping to build a lovely house in Stonington, Conn., where he lived for most of the rest of his days (fourth image). It was and is a handsome home, and it has been a National Historic Landmark since 1996, and is now the home of the Stonington Historical Society. I found on their website a photo of the house interior (fifth image), which makes me want to visit in the worst way, with four sailing-ship models visible, suggesting that there are more. The oil painting over the mantle depicts Palmer, but it does not show up, except as a thumbnail, in any searches, or else I would have used it for our first image.

We have no books by Palmer, because as far as I can tell, he never wrote a book or even an article. But he did include a cupola on the top of his house, with a widow's walk that looks out over the Sound (fourth image). Since he must have known that his seafaring days were over, this was an act of sheer hubris on his part, to let passers-by know there was no landlubber living in that house.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.