Scientist of the Day - Nadar

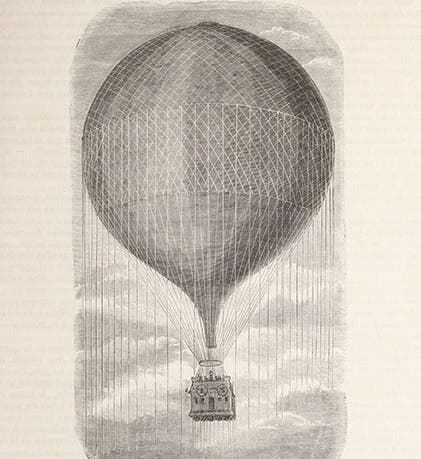

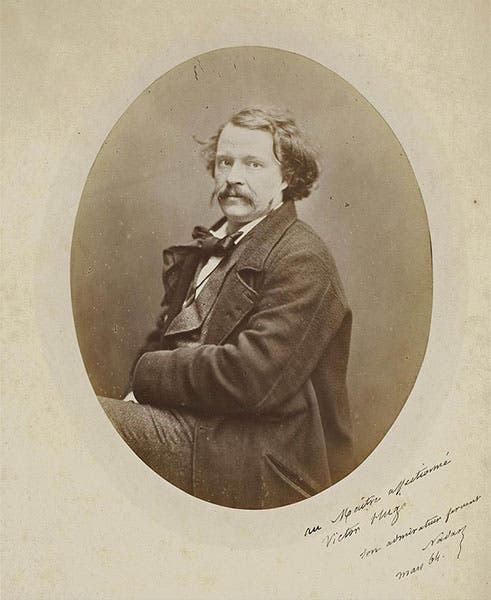

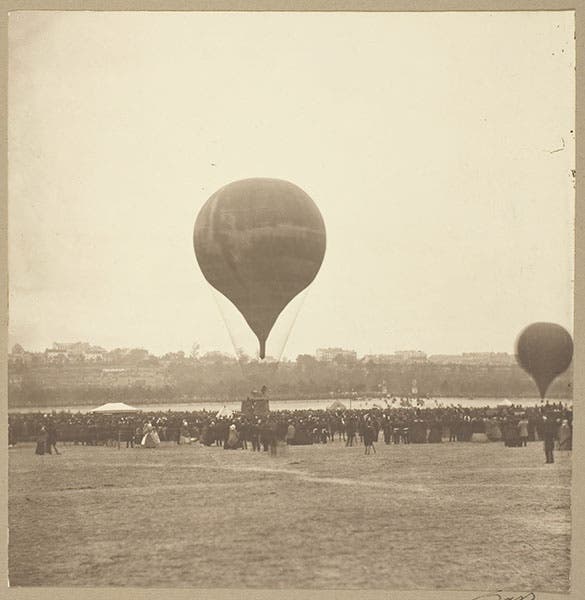

Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, a French photographer and balloonist, known nearly always by his adopted name of Nadar, died Mar. 20, 1910, at the age of 89. Nadar specialized in portraits and photographed many notable French men and women during his career. But we are more interested here in his second avocation as a balloonist. Nadar first took a camera up into a hot-air balloon in 1858, thereby becoming the first aerial photographer we know about. He was then seized by a desire to build his own balloon, and he wanted it to be the largest ever constructed and flown. By 1863, Le Géant was ready to ascend. Almost 200 feet tall, it was stitched together from 22,000 yards of silk. The usual open basket was replaced with a wicker apartment, with parlors, a darkroom, and a full balcony on top (first image and third images). The ballooning world had seen nothing like it.

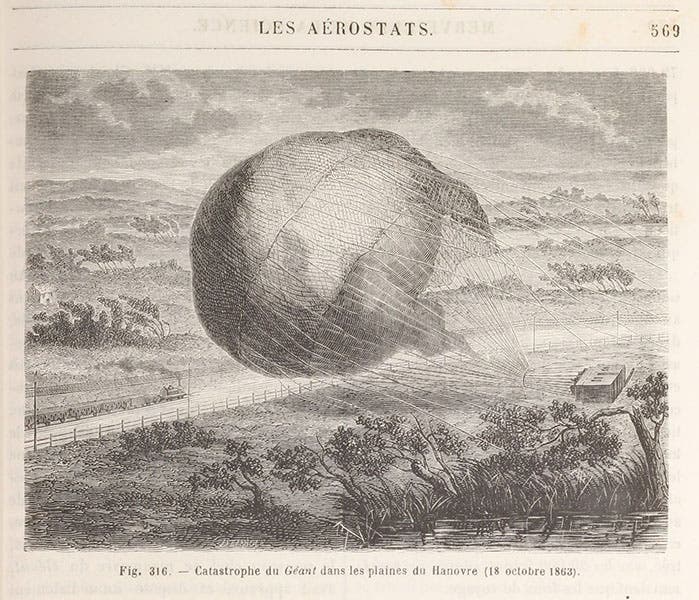

Le Géant made its first ascent on Oct. 4, 1863, carrying 12 passengers. Half-a million people watched it take off from the Champs de Mars in Paris. This first flight was short, as the balloon descended after only 15 minutes. A second ascent was readied for Oct. 18 (fourth image, below). This time the balloon stayed aloft, drifted up toward Belgium, and then east overnight into German airspace, where the passengers watched a glorious sunrise. But then came disaster. Nadar, worried about the heat of the rising sun and its effect on the gas bag, had the balloon descend to a lower altitude. They encountered a windstorm near the ground and, unable to rise again, the gondola was dragged across the ground at high speeds, narrowly missing a train, and spilling all the occupants out across the countryside like tipped cows, before the balloon burst and the gondola careened to a halt (fifth image, below).

The second flight of the Le Géant became as famous as the first flights of the Montgolfier brothers back in 1783, and the Le Géant and its bouncing finale were widely reported and imaged in the press. Louis Figuier, only a few years later, published his 4-volume Les merveilles de la science (1867), and he included in his second volume an account of the 1863 ascents, including a wood-engraving of the balloon ascending, and another of the gondola being dragged across the ground (our first and fifth images). Le Géant was repaired and made three more flights before being retired, and Nadar kept his interest in ballooning, but soon, more and more of his time was taken up with his successful photographic business.

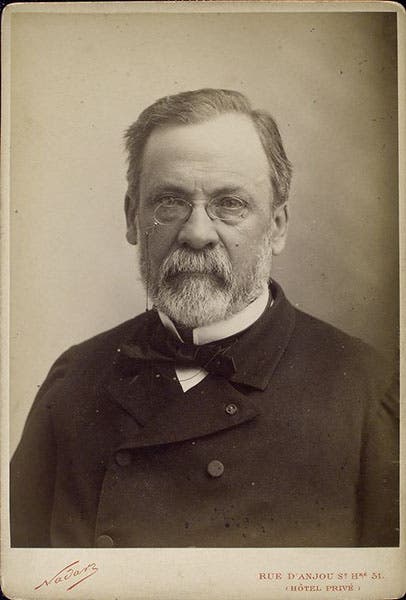

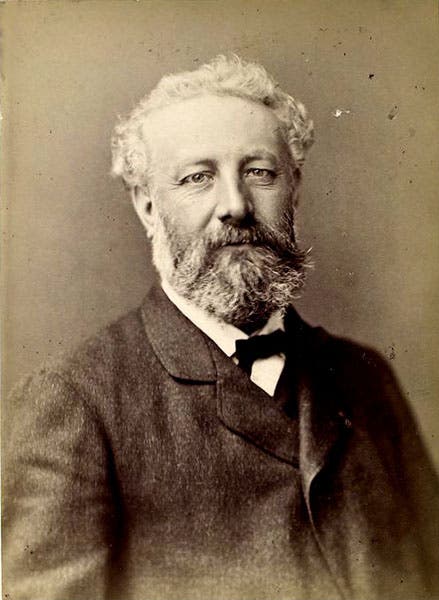

Most of the subjects of Nadar’s famous portraits were literary friends, such as Alexandre Dumas and Sarah Bernhardt. But he did portray several scientists, including Louis Pasteur and Jules Verne (sixth and seventh images, above). I am neither a photographer nor a historian of portrait photography, so I cannot usefully compare Nadar’s work to that of Julia Cameron, who also photographed many scientists, including Charles Darwin. But I imagine a comparison by an expert would be illuminating.

Nadar’s most notable photographic encounter with a scientist was a series of interviews he did with Michel Chevreul in 1886. Chevreul was a noted chemist and head of the Gobelins Tapestry works, where he developed and applied a theory of color to the dyeing of fabrics. In 1886, he celebrated his 100th birthday, and Nadar was there to celebrate it with him. While they chatted, Nadar's son Paul Nadar photographed the interviews. The next month, the newspaper Le Journal Illustré published an article by Nadar, “L'Art de vivre cent ans. Trois entretiens avec Monsieur Chevreul " with a photograph of Chevreul on the cover and 12 more in the text. It is considered, by photojournalists, the first exercise in photojournalism ever. There is a complete set of 27 photographs of Chevreul and Nadar by son Paul in the Wellcome Collection in London. In many of the photos, Nadar has his back to us, which is fine if Chevreul is the subject, but for this occasion, I chose one that shows both Chevreul and Nadar to mutual advantage (eighth image, above).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.