Scientist of the Day - Michelangelo Ricci

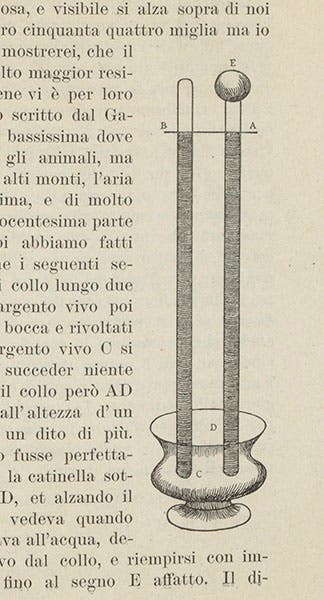

Michelangelo Ricci, a Roman mathematician and Church official, was born Jan. 30, 1619. At the Sapienza (University of Rome), Ricci was taught by two prominent Galileans, Benedetto Castelli and Evangelista Torricelli, and he remained on close terms with both for the rest of their lives (in the case of Torricelli, that was not a long time). Ricci is best known for being the recipient of a letter from Torricelli, dated June 11, 1644, in which Torricelli described how to make a vacuum by filling a two-cubit (116 cm.) glass tube with mercury, inverting the tube into a bowl of mercury, and observing thel fall of the mercury in the tube to a level of little more than a cubit and a quarter, or about 76 cm (30 inches). The now-empty space in the top of the tube was, Torricelli, claimed, a vacuum. He also began his letter with the astonishing assertion: "We live immersed at the bottom of a sea of elemental air, which by experiment undoubtedly has weight, and so much weight that the densest air in the neighborhood of the surface of the earth weighs about one four-hundredth part of the weight of water" – astonishing because no one before had suggested that air has any weight at all. Torricelli implied that the mercury in the tube was held up by the weight of the atmosphere pressing down on the mercury in the bowl. These two assertions, made within the compass of a single sheet of parchment, mark the beginning of a revolution in pneumatics and set the stage for the invention of the air pump, the main experimental tool of early scientific societies. Since Torricelli died just 3 years later, without writing any more about his discovery, except for a single follow-up letter to Ricci on June 28, 1644, the original letter to Ricci is especially precious.

Ricci's letter has been preserved; it is now in the archives of the Museo Galileo in Florence. The two images of the letter's recto and verso that the museum has posted for public viewing (second and third images) are too small to allow them to be read, but the letter is available (transcribed) in the Opere di Evangelista Torricelli (1919), and a translation into English is available . Most discussions of the letter also reproduce a diagram depicting two ‘Torricellian tubes' with the mercury levels just below the tops of the tubes. This diagram is not in the original letter in the Museo Galileo, but it is in the Opere (third image). Whether it dates from Torricelli’s time, or was created by the editors of the Opere (the most likely guess), I have been unable to establish with certainty. Presumably, with the help of an informed reader or two, we will sort this out.

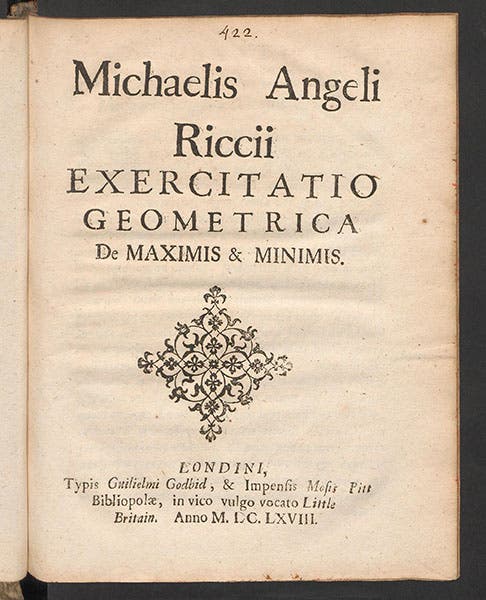

There are a number of letters to and from Ricci in Torricelli’s Opere, but most concern geometrical problems, not pneumatics. Ricci published only one treatise of his own, a short pamphlet on maxima and minima called Exercitatio geometrica that was printed in 1666. We do not own this, nor does any other U.S. library that I know. The pamphlet was reprinted two years later and attached to Nicholas Mercator’s' (1668), which is slightly more common, although we do not own that either. The entire book is available on the Swiss website e-rara; we show here the title page of Ricci’s reprinted treatise (fourth image).

Ricci was appointed Cardinal one year before his death in 1682, and perhaps that allowed him or his heirs to commission a splendid portrait sculpture that surmounts his grave in a chapel in San Francesco a Ripa (Saint Francis on the Bank) in Rome (first image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.