Scientist of the Day - Michel Foucault

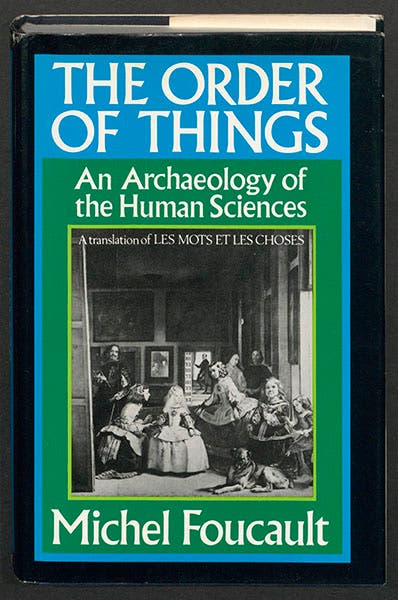

Michel Foucault, a French philosopher, was born Oct. 15, 1926. At the College de France, he was Professor of the History of Systems of Thought, which was a pretty post indeed, since you can teach about anything you want under that rubric. Foucault is best known for his studies of social institutions, such as mental hospitals and prisons, but for me, his most important book was Les Mots et les choses ("Words and Things"), published in 1966 and translated into English as The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences in 1970 (second image).

Michel Foucault’s The Order of Things, the English translation of Les Mots et les Choses, 1970 (author’s copy)

Foucault maintained that different historical periods had different ways of looking at nature that determined what scientists saw and thought important. He called these mental frameworks "epistemes." Foucault pointed out that in the Renaissance, naturalists like Conrad Gessner primarily looked for resemblances and similitudes when they studied the world, which is why their books, such as Gessner's History of Animals, 1551, contain so little zoology and so much information on proverbs, emblems, fables, myths, etc. Foucault argued that this resemblance episteme suddenly yielded, around 1650, to one that he called the "classical" episteme that was concerned with finding order in nature, rather than similitudes, and the scope of natural history changed dramatically, with taxonomy now at the focus. This book was a major influence on my own work on emblematic natural history of some years ago, since Foucault really does help understand the difference between Gesner's natural history and the natural history of Linnaeus and Buffon.

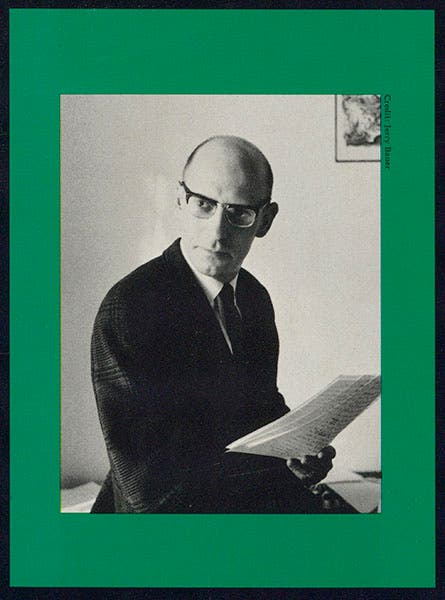

Portrait of Michel Foucault, from the dust jacket of The Order of Things, 1970 (author’s copy)

Foucault claimed in the “Preface” that he was inspired to write The Order of Things when he came across a passage in an essay of Jorge Luis Borges which, citing a “certain Chinese encyclopaedia”, divides animals into: “(a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camel-hair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies.” While we have referred to Borges several times in these posts, for example when we recently wrote on Franz Kafka, we have never profiled the great Argentinian essayist, who had a great deal to say about science and the way we see the world. We hope to remedy this deficiency next Aug. 24, Borges’ birthday.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.