Scientist of the Day - Michel Chasles

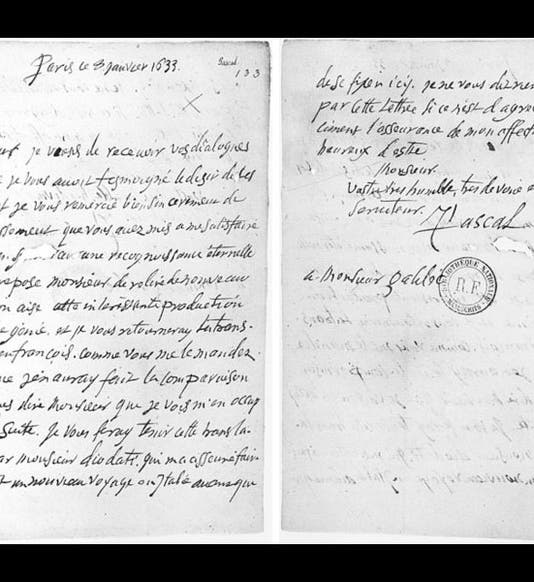

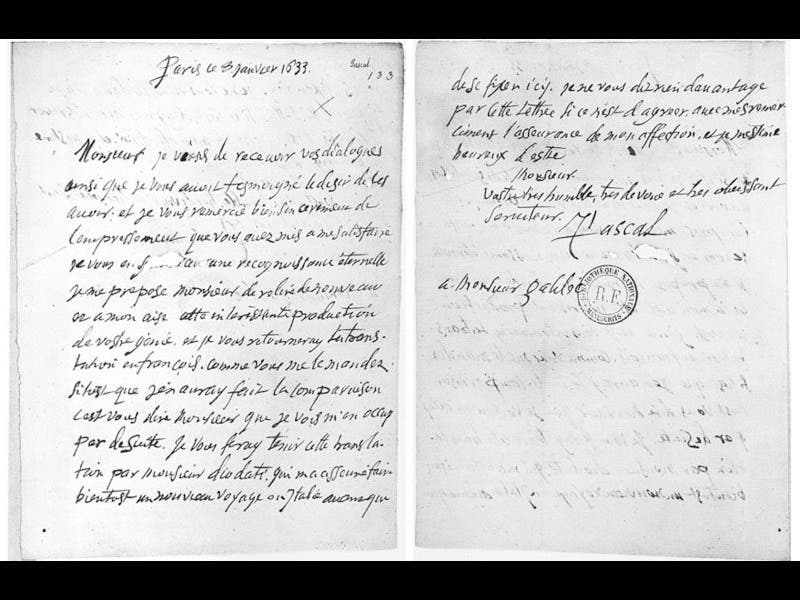

Michel Chasles, a French mathematician, was born Nov. 15, 1793. Chasles was a highly-respected mathematician; he wrote an important history of geometrical methods, was appointed to a chair at the Sorbonne, and when the Eiffel Tower was erected in 1889, Chasles was one of 72 French scientists to have his name inscribed on the second level. But Chasles is remembered today mostly because he had an inordinate fondness for manuscript letters, acquiring a vast collection over the course of about 8 years. He bought them all from one dealer, Denis Vrain-Lucas, who was in some ways a genius, but also a man totally without scruples. The first letter he sold to Chasles was purportedly written to Galileo by 10-year old Blaise Pascal, in which Pascal revealed that he had discovered universal gravitation, some 50 years before Isaac Newton stumbled upon it. The letter survives, in the Bibliotheque Nationale (first image), and you can make out Pascal's signature, and Galileo’s name as addressee, and the date, 1633. Chasles was eager for more letters, and Vrain-Lucas was eager to supply them. Soon Chasles had letters from Thales the Presocratic describing his theory of matter, from Alexander the Great, giving advice to Aristotle about visiting Gaul, from Charlemagne to Alcuin of York (second image), from Doctor Castor the Roman botanist to Jesus Christ, and from Rabelais to Emperor Charles V--all written on water-marked paper in early-modern colloquial French, which is not surprising in the case of Rabelais, but somewhat unexpected from the likes of Thales and Alexander the Great. Chasles bought, by Vrain-Lucas's own reckoning, some 30,000 letters like this--every one a forgery, written by Vrain-Lucas himself.

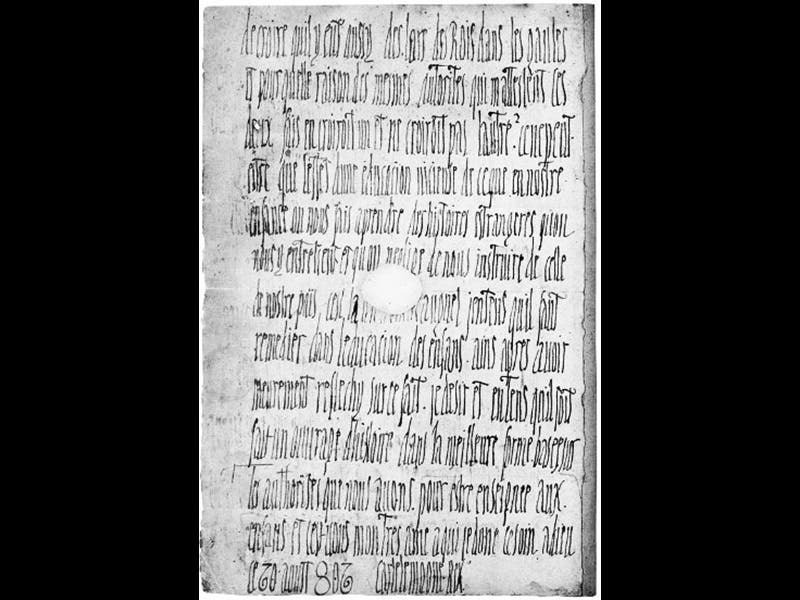

All might have been well, had Chasles not attempted in 1867 to convince the French Academy of Science that Pascal had discovered the law of gravitation, using the letter to Galileo as evidence. Chasles actually defended the authenticity of his letters pretty well before that august body, but the truth was now out there for anyone wanting to look, and one prosecutor did look, and was provoked enough to bring Vrain-Lucas to trial for forgery in 1869. Poor Chasles, 76 years old, was subpoenaed and had to admit on the witness stand that he had bought letters from Joan of Arc (third image) and Mary Magdalene, all in French. Vrain-Lucas was convicted and sentenced to two years in prison.

In most accounts of the Chasles-Vrain-Lucas affair, commentators invariably marvel at the gullibility of Chasles, and at his willingness to believe that Alexander the Great wrote letters in French. Such credulity is impressive. But we are more impressed with the industry of Vrain-Lucas, who turned out 30,000 letters in 8 years, which comes to 3750 letters a year, or just over ten per day, each written by hand--presumably in many different hands, or even Chasles might have been suspicious. Chasles said that he shelled out some 140,000 francs over the eight years for his collection, which means the letters cost him less than 5 francs each, a bargain for even a forgery.

Vrain-Lucas wrote a long, charming letter to Chasles from prison, which has been translated and made available online (although it is possible that this letter too is a forgery). He reminded us that all history is re-enactment, so it is not evident why his creations were objectionable and that of academic scholars were not. He also pointed out that he was hardly guilty of fraud, since that requires a conscious attempt to deceive, and who could possibly believe that a genuine letter by Pascal could be had for 5 francs?

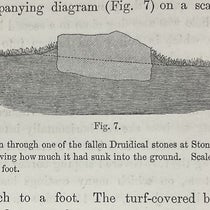

The photograph of Chasles was taken late in life (fourth image). We have three original editions of Chasles’ works and one translation in the Library, but not one of the manuscript letters that he once owned. Hardly any survive. Vrain-Lucas lamented that all but 100 of his letters were ordered to be burned, and he was certainly right about the folly of the court in executing that order. Book burning is always a very bad idea.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.