Scientist of the Day - Michael Ventris

Michael Ventris, an English architect and linguist, was born July 12, 1922. In 1900, the archaeologist Arthur Evans had discovered, at Knossos in Crete, a number of clay tablets written in 3 unknown scripts. The most tantalizing came to be known as Linear B. Evans tried for 40 years to decipher the script but was unable to do so. The tablets were written around 1400 B.C.E.

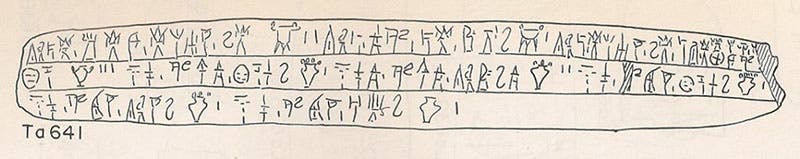

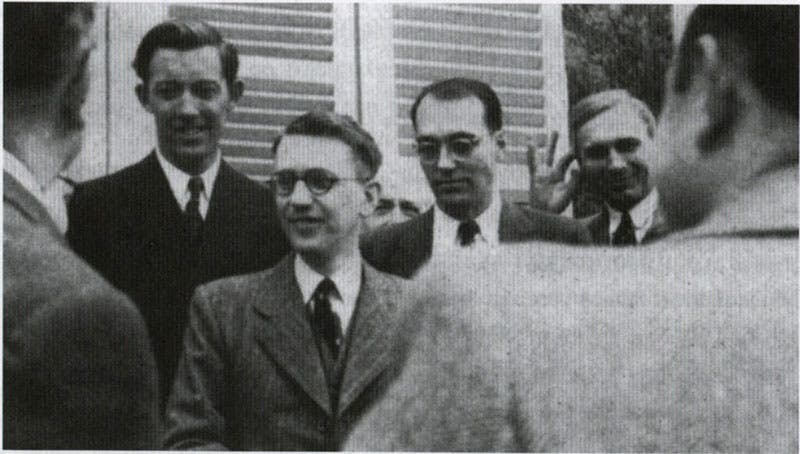

Michael Ventris with a Linear B tablet, frontispiece to Andrew Robinson, The Man Who Deciphered Linear B: The Story of Michael Ventris, 2002 (author’s copy)

Ventris first saw a Linear B tablet (and heard Arthur Evans speak) in 1936, at the age of 14, and he was immediately hooked. He would work on Linear B for the next 20 years, while also training as an architect, fighting during the war, and, because it was easy for him, learning dozens of languages. The decipherment was especially daunting because there was no Rosetta Stone or Behistun inscription with a bilingual text that could aid in the translation. It was not even known in what language the script was written, although Evans and Ventris surmised that it was either Minoan or Etruscan. This would prove to be incorrect.

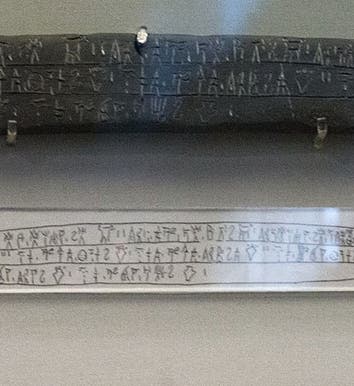

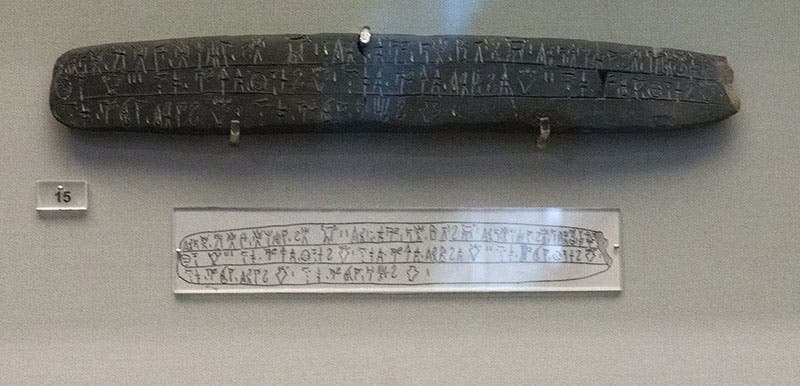

Ventris began working with John Chadwick at Cambridge in 1950, and they had his big breakthrough in 1952. Because the tablets found on Crete had some sign arrangements that were missing from those found on mainland Greece, Ventris surmised that those might represent Cretan place names, and he guessed that a certain set of signs might represent the name “Knossos”. This turned out to be correct. This meant that the language was Greek, or some form of proto-Greek. Within months, Ventris had nailed down the 79 syllabic signs, as well as their pronunciation. Verification came with the discovery of a new tablet from the site of Pylos on mainland Greece, known as Pylos 641, which had pictures of little three-legged and four-legged pots on it, as well as Linear B syllabic signs which, when translated, yielded "tripod pot" and "four-legged pot," in Mycenaean Greek (first and third images)

The successful decipherment of Linear B was announced on the front page of The Times in 1953, right next to a story about Hillary conquering Mount Everest. Ventris and Chadwick subsequently wrote and published a scholarly book, Documents in Mycenean Greek (1956), the culmination of their work in deciphering Linear B. Sadly, having conquered his own Everest, Ventris lost his direction in life, and in 1956, he died when he ran his car at high speed into a parked truck. No one knows if his death was accidental or self-inflicted. Ventris was 34 years old.

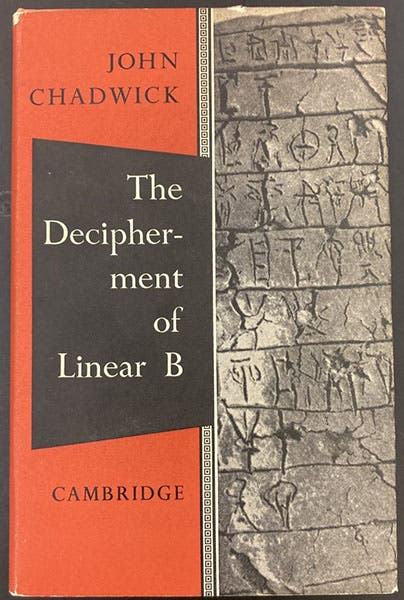

Front cover of The Decipherment of Linear B, by John Chadwick, 1958 (author’s copy)

James Chadwick wrote a book for the general public, The Decipherment of Linear B (1958), which is still an excellent introduction to the subject. The first chapter is a generous and moving tribute to Michael Ventris (fifth image). There is also an outstanding biography, The Man Who Deciphered Linear B: The Story of Michael Ventris (2002), written by Andrew Robinson. We used the frontispiece photograph of Ventris as our second image.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.