Scientist of the Day - Maurice Wilkins

Maurice Wilkins, a New-Zealand-born English physicist turned molecular biologist, died Oct. 5, 2004, at the age of 87. After World War II, Wilkins was one of a handful of physicists who read What is Life? (1944), a thoughtful book by quantum physicist Erwin Schrödinger about the physical basis of living things, and decided to apply their talents to unraveling the secrets of life.

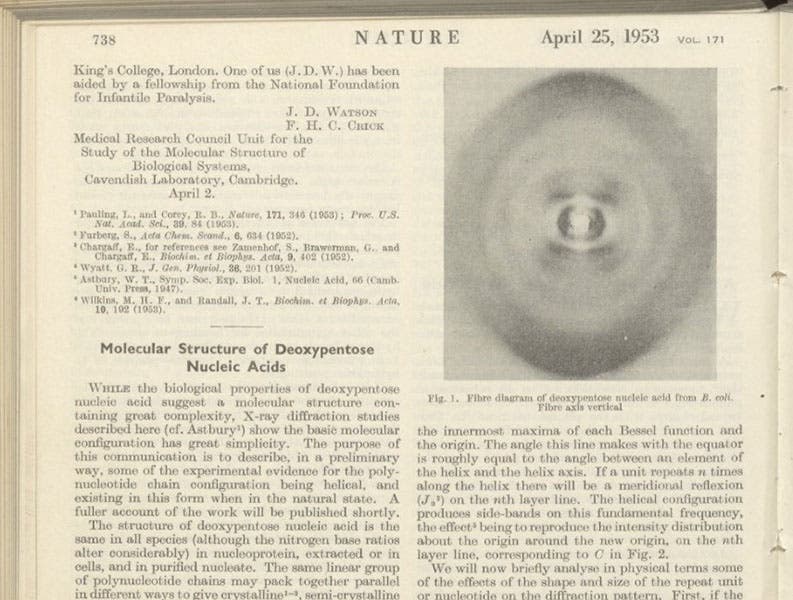

Wilkins moved to King's College, London, in 1946; by 1949, he was using the methods of X-ray crystallography to look at organic molecules, including DNA. This technique bounces X-rays off crystalized molecules, so that the reflected X-rays produce what are called interference patterns. These are not "pictures" per se of molecules, but rather images that contain clues to molecular structure, since different molecules produce different interference patterns. However, they must be interpreted, and that is where skill and experience come in.

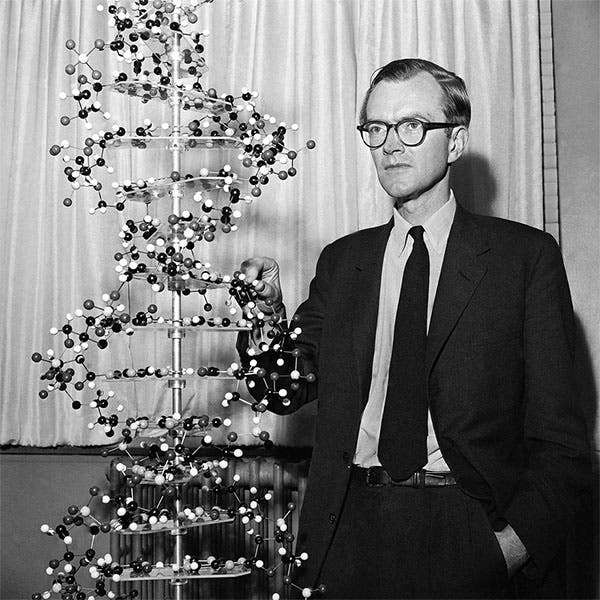

Wilkins worked as assistant director to John Randall, who had set up the Biophysics Department at Kings and brought Wilkins in. By 1950, Wilkins and a collaborator, Alex Stokes, having received excellent samples of DNA from Italy, succeeded in crystallizing the DNA and obtaining crisp X-ray photographs, which already suggested to Wilkins a helical structure. He showed one of their photographs at a professional meeting in Naples in 1951, where it was seen by James Watson, who was quite excited by what the photograph revealed about DNA structure.

In 1951, Randall hired Rosalind Franklin to work on DNA X-ray diffraction studies at Kings, and he assigned her a graduate student, Raymond Gosling, who had previously worked with Wilkins. Randall wrote Franklin a letter telling her that she and Gosling would be the only ones doing DNA work. But he did not tell Wilkins, who for good reason thought that Franklin would be working with him. As a result, there was a fundamental misunderstanding between the two that was never really smoothed over, and Franklin strongly resented it when Wilkins made any effort to interpret the results of her work.

One of the photos taken by Franklin and Gosling came into the hands of Wilkins, who showed it to James Watson when he came to visit in 1952. Watson looked at it and immediately saw confirming evidence of a helical structure for DNA. That photo is now famous and known as Photo 51. So it was through Wilkins that Watson learned of Franklin’s work.

When Watson and Francis Crick submitted their paper proposing a double-helix structure for DNA to the journal Nature, the editor, encouraged by his friend Randall, requested that Wilkins submit a paper on his X-ray diffraction studies, which he did. Franklin was not so invited, but she insisted on being included, and she was accommodated. As a result, the famous April 25, 1953, issue of Nature contains the Watson-Crick paper; another by Wilkins, Stokes, and Wilson (a PhD student) that immediately follows, with one of Wilkins’ photos of DNA; and then a third paper by Franklin and Gosling that contains photo 51. We show here the page with the end of the Watson-Crick paper, and the beginning of the Wilkins-Stokes-Wilson paper, with their photograph (second image). You can see the Franklin-Gosling photo in our post on Franklin.

Wilkins continued to work on DNA structure after 1953, helping confirm that the structure was universal in all organisms. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology/Medicine with Watson and Crick in 1962. Franklin had died in 1958 and was not eligible for a Nobel award. Had she been alive, that would have been a problem, since no more than three may share a Nobel prize, and it might have been hard to choose between Wilkins and Franklin. Neither Gosling nor Stokes was mentioned in the award. There is however a plaque at King’s College in London that honors all five of the Kings participants in the X-ray studies of DNA. Watson and Crick, those Cambridge rascals, are the ones omitted here (fourth image).

Although we already showed one photograph of Wilkins receiving his Nobel Prize, I cannot resist including one of the group photographs of all six Nobel recipients for 1962 (fifth image). The three at left, from the left, are Maurice Wilkins, Max Perutz, and Francis Crick; the two at right, from the right, are John Kendrew and James Watson. The sixth, sandwiched between Watson and Crick, was the recipient for Literature, John Steinbeck. Seldom has a man looked more uncomfortable at the prospect of a long evening at the banquet table in the company of people who speak another language entirely.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.