Scientist of the Day - Mattheus Greuter

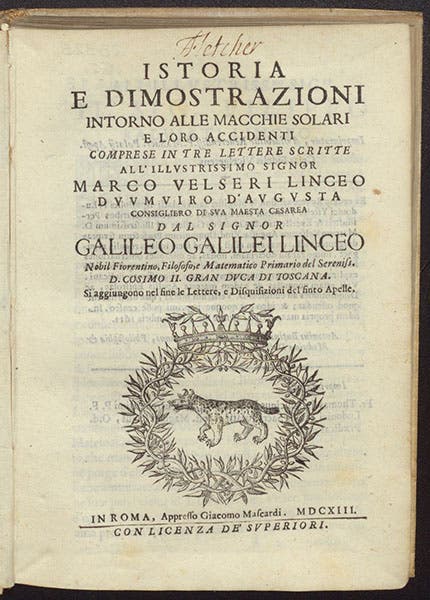

Mattheus Greuter, a German engraver, died Aug. 22, 1638, at the age of about 73. Originally from Augsburg, where he worked for Mark Welser, a banker interested in science who corresponded with all manner of intellectuals, Greuter became a lapsed Lutheran and headed for Italy for protection for his reborn Catholicism, fnally ending up in Rome, where his skill at engraving (and his association with Welser) found him ready employment. In 1611, the Jesuit astronomer Christoph Scheiner wrote three letters to Welser about sunspots, of which he claimed discovery. Welser printed them up in Augsburg in 1612 and sent copies to Federico Cesi and his Lincean Academy in Rome, of which Welser was a member, as was Galileo Galilei.

Galileo responded with his own three letters (also addressed to Welser), indicating that he considered himself the discoverer of sunspots, and recording and discussing his own sunspot observations. Scheiner and Galileo differed in their interpretation of what they saw. Scheiner, perhaps subscribing to the Aristotelian doctrine of the perfection of celestial bodies, did not think the spots were on the solar surface, but were rather small bodies casting shadows on the Sun, so the Sun was not really blemished and spotted. Galileo, on the other hand, proposed that the spots were smoky vapors emitted from the Sun, and since they were on the surface, were evidence that the Sun rotates.

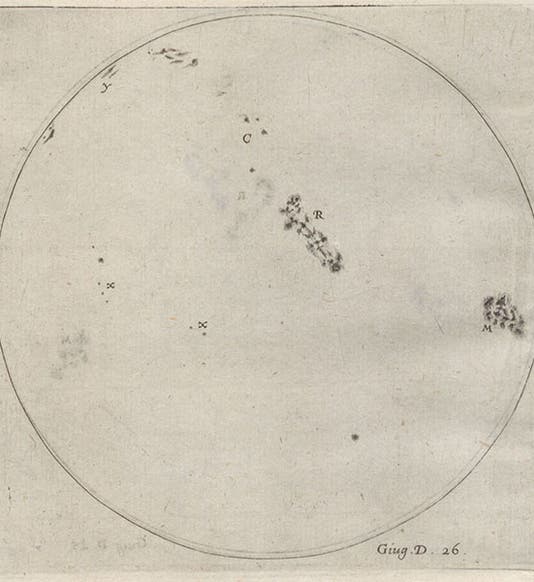

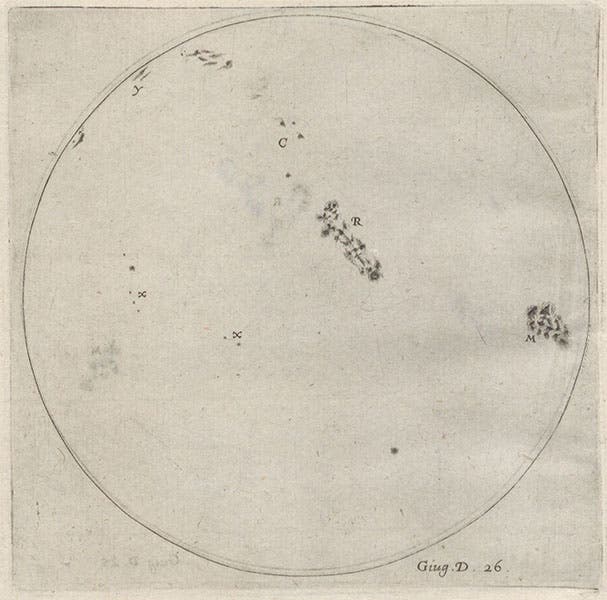

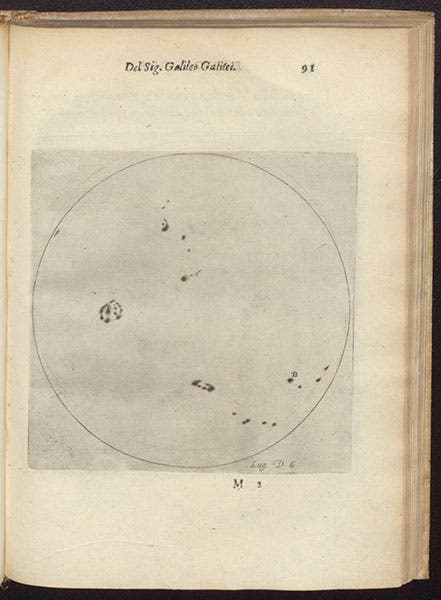

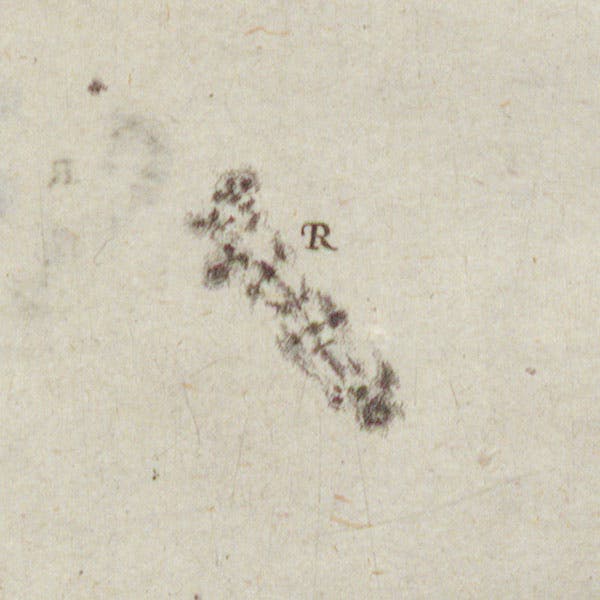

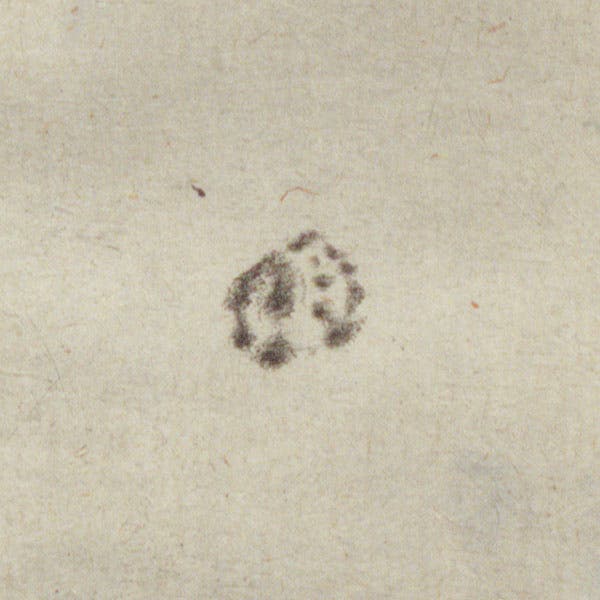

Cesi decided to publish Galileo's sunspot letters and the letters of Scheiner in one volume (second image). But he needed an illustrator. Scheiner had employed Alexander Mair (or perhaps Welser had hired Mair – both were from Augsburg) to illustrate his sunspot observations, which Mair had done with small precise engravings (you can see some of these in our post on Scheiner). Mair had earlier drawn the constellation figures for Johann Bayer's marvelous star atlas, the Uranometria (1603), so he was an excellent choice. Cesi was very much against using an Italian engraver, for some reason, and so, from a short list of three, he selected the German Greuter to do the engravings for Galileo's sunspot book. It was an inspired choice. Greuter worked hard to produce 38 large copper-plate engravings of Galileo's careful drawings. Since Galileo saw the sunspots as smoky and cloudy, Greuter had to supplement his engraved outlines of the solar disc with etched sunspots, which do indeed seem cloudy and ephemeral. We show here several of the full-page engravings by Greuter (first and third images), and two details of etched sunspot groups from those plates (fourth and fifth images).

Greuter apparently stayed in the good graces of Cesi and the Lincean Academy, for when, in 1625, the Academy published a broadsheet with the first depiction of insects seen under a microscope, in this case three bees, observed by Francesco Stelluti, and arranged in the form of the three-bee crest of new Pope Urban VIII. It was Greuter who did both the drawing and the engraving for this large showy piece (which is very scarce, and which we do not have in our library; see sixth image). There is more to the story, as the large print was later reformatted into a much smaller engraving and included in a book that we do have in our library, and which may have been illustrated by Greuter. We will tell the full story of Greuter and the Barberini bees on another occasion.

There is, to my knowledge, no surviving portrait of Greuter, unless you can find a face hidden in one of his sunspot etchings, as people do in drawings of Mars. Our copy of Galileo's Letters on Sunspots is available online, if you would like to make a search.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.