Scientist of the Day - Mary Emily Eaton

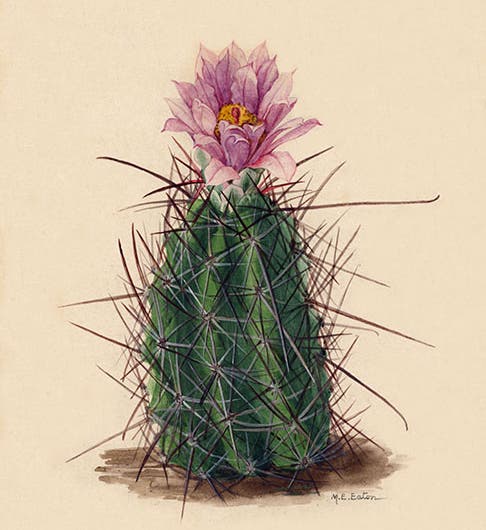

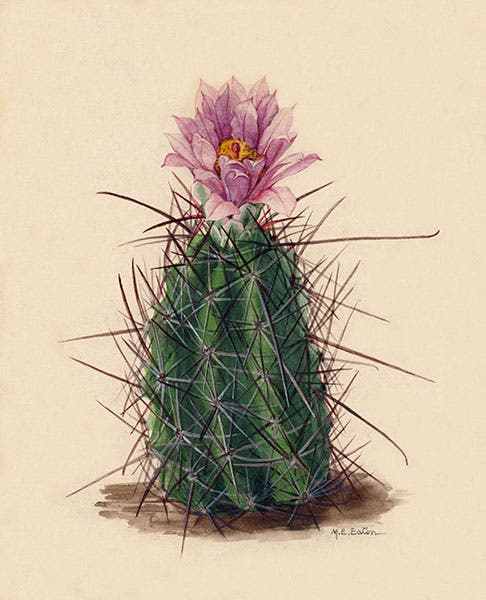

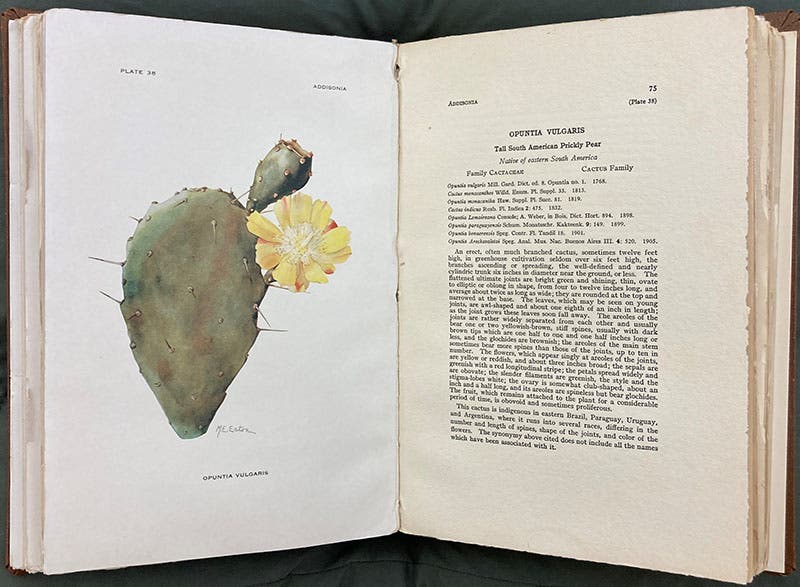

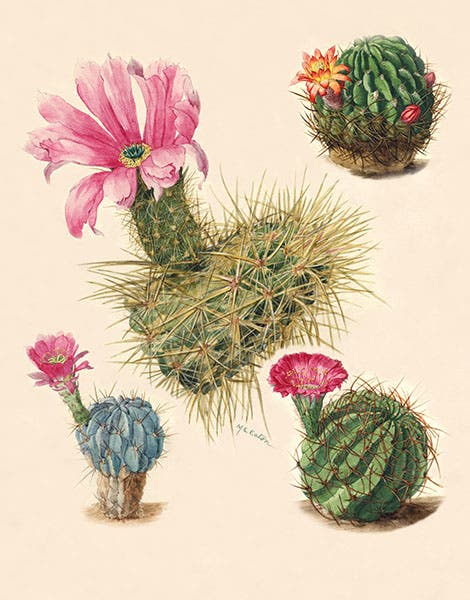

Mary Emily Eaton, an English/American botanical artist, died Aug. 4, 1961, at the age of 87. Eaton was born in Coleford, Gloucestershire, attended various art schools in Greater London, then visited her brother in Jamaica in 1909, where she started painting insects. She moved to New York City to look for work,, which she found at the New York Botanical Garden (NYBG), since she (and the Garden) discovered she was quite good at drawing plants and flowers. Nathaniel Britton and Joseph Nelson Rose were working on an encyclopedia on cacti, and Eaton was soon enlisted in drawing cacti, species by species. The first volume of the four-volume set, The Cactaceae, would not appear in print until 1919, but many of Eaton’s illustrations were published in Addisonia, the journal of the NYBG, which was launched in 1916. This is a lovely journal, with the text printed on thick wove paper, but the reproductions of Eaton’s watercolors are mediocre, as most half-tone color reproductions were at the time (third image).

Eaton's work also came to the attention of the editors of National Geographic, and in 1915, they published an article on the “Wildflowers of North America,” which was really just a collection of Eaton's watercolors, with minimal text. Two years later, they asked Eaton to draw all the state flowers, and published them in 1917. In all, she illustrated 7 articles on flowers for the National Geographic. We show the page from the June 1917 issue depicting the state flowers of Arizona and New Mexico, both cacti. We could have shown the Kansas sunflower, but it seemed out of place among all the succulents.

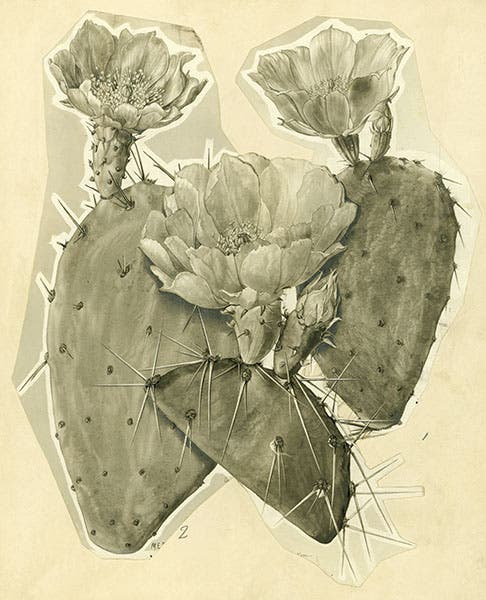

I would show some of the Eaton watercolors that were reproduced in The Cactaceae, but for a dilemma – our copy is a 1937 reprint, and all the images are in black and white. I do not know whether the 1919-23 original printing contained color reproductions. If so, it is probably an impressive work. But the 1937 reprint does scant justice to Eaton’s original paintings.

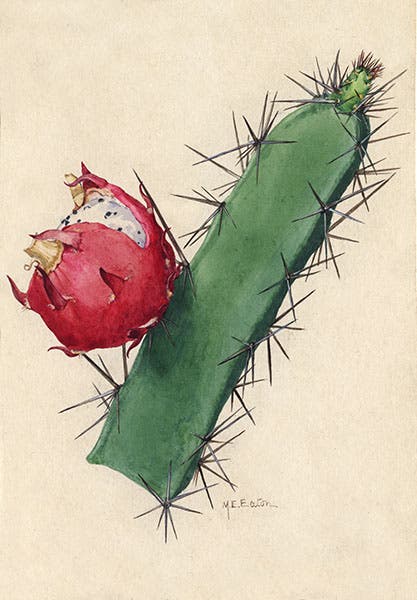

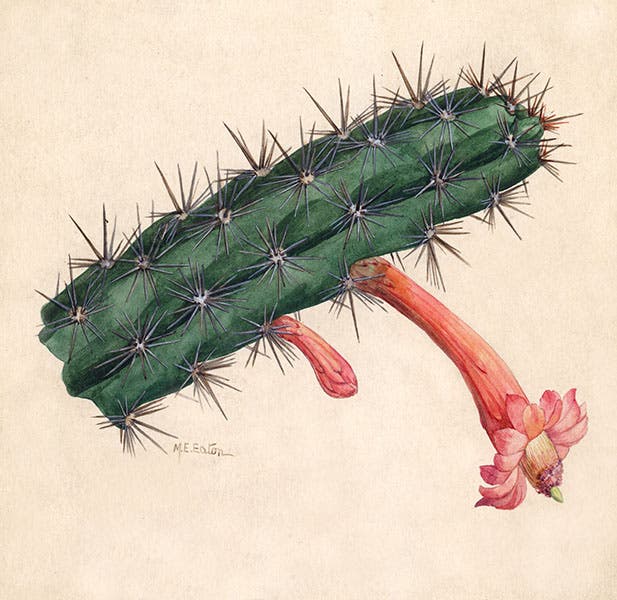

Fortunately, hundreds of original Eaton watercolors survive, in the collections of the Smithsonian Institution, the New York Botanical Garden, and the Hunt Center for Botanical Documentation in Pittsburg. I have drawn the rest of our examples today from the collection at the Smithsonian Institution, because they are high-resolution and are easy to find. And they are just beautiful. I selected, from the 287 watercolors that have been digitized: Whipple’s fishhook cactus (1912; first image); Englemann’s prickly pear (undated; fifth image, above), the Queen of the Night (1915; sixth image, just above), the octopus cactus (1915, seventh image, just below); and the hatpin cactus (eighth image, below).

The eighth image is of interest because, if you go the webpage of the Smithsonian Institution’s Objects of Wonder exhibition, intended to showcase the breadth of their collections, you will see that the curators selected 7 objects to represent the seven departments of the National Museum of Natural History. As you scroll down, you will encounter object 1, a mosasaur tooth, representing the Department of Paleobiology, then a burying beetle, for the Department of Entomology, and for the third object, representing the Department of Botany, you will see Eaton’s watercolor of the hatpin cactus, Ferocactus rectispinus. To be chosen to represent hundreds of thousands of objects in a department is quite an honor, even if, in this case, it is a posthumous one.

Our last selection (ninth image) shows four cacti at once, including Englemann’s hedgehog cactus, and it is just gorgeous, which is why I saved it for last. If you want to see more of Eaton’s watercolors at the Smithsonian, go to this page, click on the Botanical Art tab at the top, then type in “Eaton, Mary Emily” in the opening for “artist,” then Search. You will get 29 pages of results, but they are in alphabetical order by genus and species, and easy to find. Clicking on any one brings up a page of documentation and a high quality image, just like the ones we used here.

Eaton unfortunately lost her job at the NYBG in 1932, during the Great Depression. She never found another good position in the United States, and she returned to the family home in Newton, Somerset, in 1947. There, she died on this day in 1961. Her grave cannot be located by any of the grave-finding services, but since her mother and father are buried in St. Peters Churchyard, North Newton, it is likely that Mary Eaton's grave is somewhere nearby. I hope its location is known to somebody, and that cacti appear sporadically on her gravesite, in honor of one of the greatest portrayers of succulents who ever lived.

There is only one known portrait of Mary Emily Eaton, in the archives of the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburg, which we used here (second image). There is an excellent short biography of Eaton, by Larry W. Mittich, available online; it appeared in the journal Haseltonia in 2000, in an issue we do not own.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.