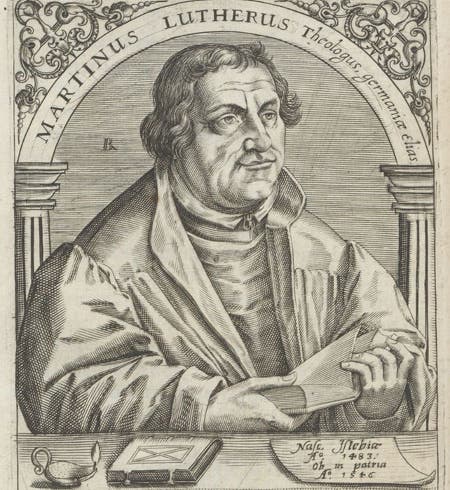

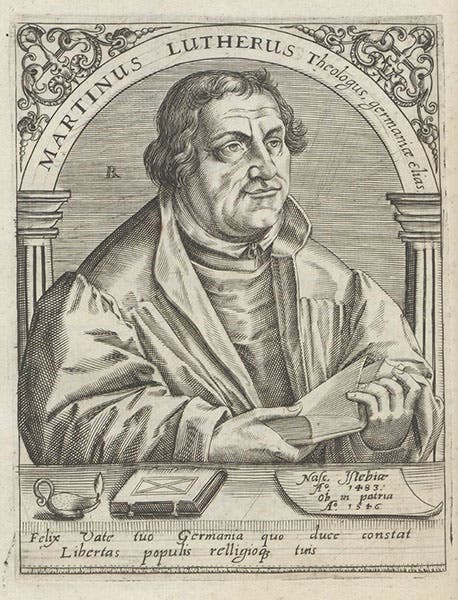

Scientist of the Day - Martin Luther

The Protestant Reformation is usually considered to have begun on Oct. 31, 1517, when Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-five Theses to the door of the church in Wittenberg. Luther was a Catholic priest who objected to the Church practice of selling indulgences, where sins were redeemed for cash. Many of his 95 Theses called for an end to this practice.

Luther had not intended to form a new Christian sect, but when he was excommunicated by the Church, he had little choice, and the Lutheran reform movement grew, especially in Germany. Luther called for a more personal relationship with God, dismissed the role of the Church as mediator, and suggested that the faithful could read the Bible directly, without the intervention of a priest. “Faith alone, grace alone, scripture alone” was the mantra of the new faith. Good works, traditional Church practices, and the priesthood were irrelevant to Luther’s vision of Christianity. Many came to share that vision, and the Protesant reformation was off and running.

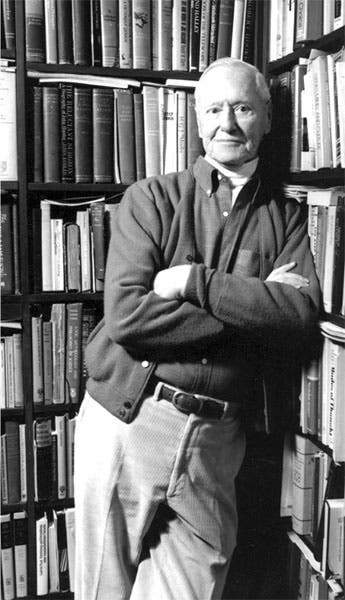

In 1938, a young sociologist, Robert Merton, proposed that the rise of Protestantism was intimately connected to the scientific revolution of the 17th century in England. Merton argued, in what is now called the "Merton Thesis", that, just as Protestantism encouraged individuals to read the Bible and find God for themselves, forgoing the intermediary of ecclesiastical authorities, so too did Protestant natural philosophy, which abandoned the authority of Aristotle and encouraged looking at nature firsthand. Merton thought the thesis applied especially well to England, which joined the Reformation in the time of King Henry VIII, and all of whose scientific innovators, such as Isaac Newton, Robert Boyle, and Robert Hooke, was Protestants.

The Merton thesis first appeared in print in 1938, in an article in the journal Osiris inelegantly titled: “Science, Technology & Society in Seventeenth Century England.” We show Merton’s preface to his article in Osiris (third image). It finally appeared in book form in 1970 (fourth image) and then in paperback, all with the same bland title.

The Merton thesis was quite influential for half a century, although it has now lost its clout, as many scholars, including yours truly, have pointed out that for every Protestant looking at nature in a particular way, one can find a Catholic doing pretty much the same thing. However, discussions of the Merton thesis continue to be lively and provocative.

One can also make a good argument for a Merton thesis in art (which we should call the Alpers thesis, after the art historian, Svetlana Alpers, who has attempted this), since Dutch Protestant artists in the 17th century avoided the grand historical and religious paintings of their Italian counterparts and took a very personal look at nature, painting still lifes and genre scenes instead of saints and mythological heroes. The Merton thesis would appear to have tendrils that still insinuate themselves.

Title page, Science, Technology & Society in Seventeenth Century England, 1st book edition, 1970 (author’s copy)

I met Robert Merton once, at a conference held in Jerusalem in 1988, on the 50th anniversary of the Merton thesis, where Merton was the guest of honor. I told him how much I admired his other book, On the Shoulders of Giants: A Shandean Postscript, one of the great paeans to, and send-ups of, academic scholarship, probably the most delightful book about scholarship ever written. When we got back home, he sent me a personalized copy of the book, which I treasure. Some day we will do a post on OTSOG, as academics in-the-know refer to it, so that you can share my admiration for the book.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.