Scientist of the Day - Marie Curie

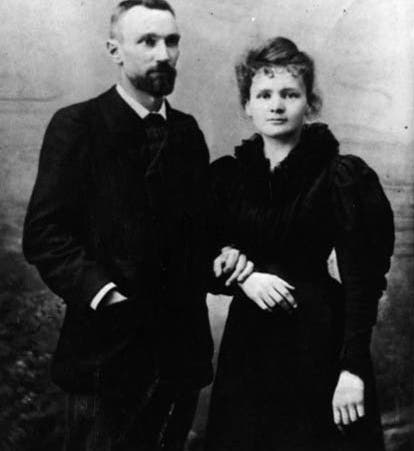

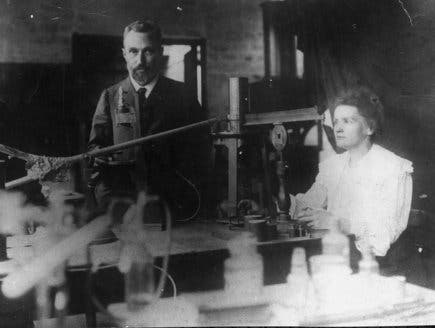

Marie Sklodowska, a Polish chemist, was born Nov. 7, 1867, in Warsaw. While studying at the Sorbonne, she met Pierre Curie, eight years older and already a professor, and they were much taken with each other. Marie, an ardent Polish naturalist, had sworn she would only marry a Pole, but when she returned to Poland after graduating, no one would hire her, in spite of her outstanding qualifications, so she drifted back to Paris and Pierre, and they were married in 1895 (first image). Five months after their wedding, X-rays were discovered, and all hell broke loose in science labs throughout Europe. Radioactivity was the next to burst upon the scene, discovered by Henri Becquerel in 1896, and the Curies realized this was the perfect field for a husband-wife physicist/chemist team (second image). By July of 1898, they had successfully isolated a new element from pitchblende, a uranium ore, which Marie named "polonium," after her cherished homeland. Six months later, they discovered another new element in pitchblende, this one much more radioactive that uranium itself, and this element they named radium. The discovery was announced just after Christmas, 1898, a scant three years since Roentgen had given the world a Christmas present of X-rays.

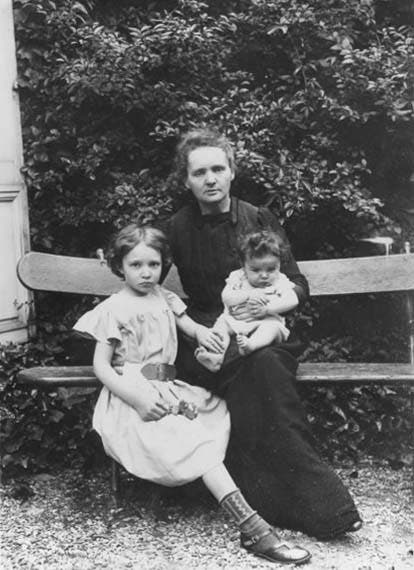

For their pioneer researches into the nature of radioactivity, Marie and Pierre shared the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903 with Becquerel, and Marie didn't even mind the career change from chemist to physicist that the award implied. By 1905, they had a family of two girls, Irene, age 8, and Eve, age 1, and were blissfully happy as parents and as the King and Queen of French science (third image).

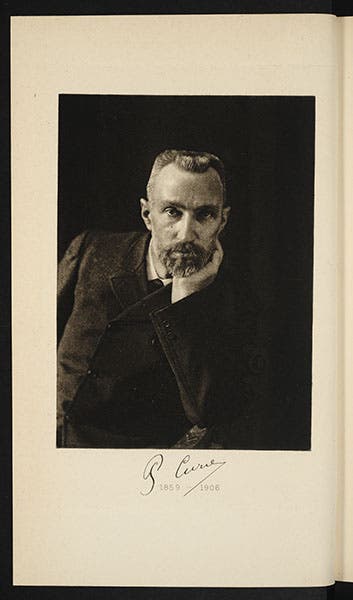

What a tragedy, then, when Pierre, on Apr. 19, 1906, stepped in front of a horse-drawn carriage near the Pont Neuf in Paris and was killed. Life was never the same for Marie. She would be appointed Pierre's successor as Professor at the Sorbonne, and she would get a second Nobel prize in 1911, this time in chemistry, thereby becoming not only the first woman to win a Nobel prize, but the first person to win a second Nobel award. She would do productive work for several more decades, as would her two daughters, but life was never the same after the loss of Pierre.

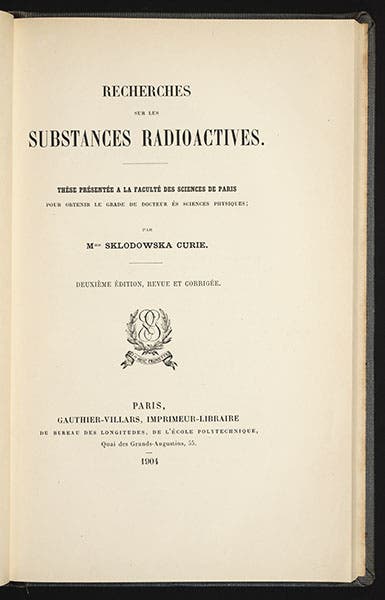

We have in our Library Marie’s doctoral thesis, Recherches sur les substances radioactives (1903; we have the 1904 printing, fourth image), and her 2-volume Traité de radioactivité (1910; fifth image).

The Traité has a frontispiece portrait of Pierre that is often used to illustrate biographies of Pierre; we used it ourselves when we featured Pierre as Scientist of the Day several years ago, but we used there a secondary source. This time we use the real thing.

Marie died of aplastic anemia in 1934, the result of continuous radiation exposure for well over 30 years, at a time when radiation danger was not understood, and radium was actually thought to have beneficial therapeutic value. Marie once described how wonderful it was, in the early years, when she and Pierre would go to their lab at night; all the tubes and capsules of samples would be shining with an ethereal gleam, which Marie described as a lovely sight, the tubes glowing like tiny fairy lights. That is quite a sobering description, knowing what we know today. It is a fact that Marie’s papers, at the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, are still highly radioactive; they have to be stored in lead-lined boxes, and are only available to researchers who wear protective clothing.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.