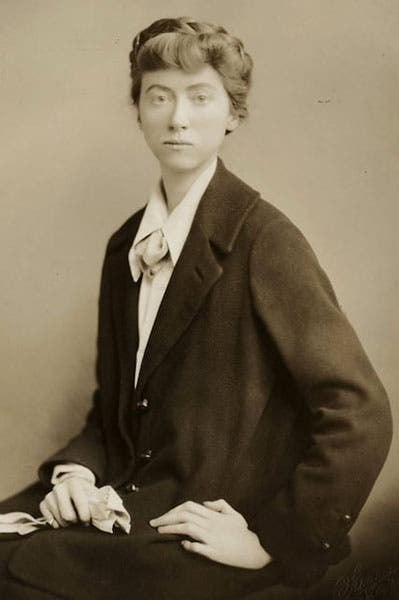

Scientist of the Day - Marianne Moore

Marianne Moore, an American poet, was born Nov. 15, 1887, in Kirkwood, Missouri. Her father disappeared before she was born, and she was raised by, and devoted to, her mother. Moore attended Bryn Mawr College, where she began writing poems. Mother and daughter (there was also an older brother), moved to New Jersey to be near New York City, and then to New York City itself, where they lived in Greenwich Village. Moore had begun publishing her poems in 1915, and it was about the time of her move to New York that she published the poem that is the subject of today's post: The Fish. It appeared in The Egoist in 1918, and then was included in her first authorized book of poems, Observations, in 1921. The Fish is one of my favorite poems, and I have always wanted to write about it, since it has an evident science connection, but I possess no expertise in poetic analysis, so I have, until now, resisted. But I finally realized that, of all works of art, a poem is best able to speak for itself, and does not need an interpreter, if the poet has done his or her job well. I learned this from Dava Sobel's column, "Meter," in Scientific American, where each monthly poem stands on its own, without analysis.

So the poem will follow shortly. But first, a few words of guidance (but not interpretation). The Fish is a formal, intricately constructed poem, even though it is also witty, beautiful, and insightful. When you read it to yourself, you will be looking at the printed text, but if you have it read to you, you should also have the printed text before you. There are lots of readings on YouTube, but you should choose one where the poem is visible on the screen. A reading by Al Gore is a good example of how to combine the visual aspects of the printed poem with its audible voice. There was also an episode of Poetry in America about The Fish, where the poem is read by a variety of readers, but with good visuals, and the text onscreen. If you do watch the Poetry in America 27-minute episode, be advised that you will also be subjected to a variety of interpretations, which, if that suits you, is fine. My appreciation of The Fish was relatively unscathed by all the commentary.

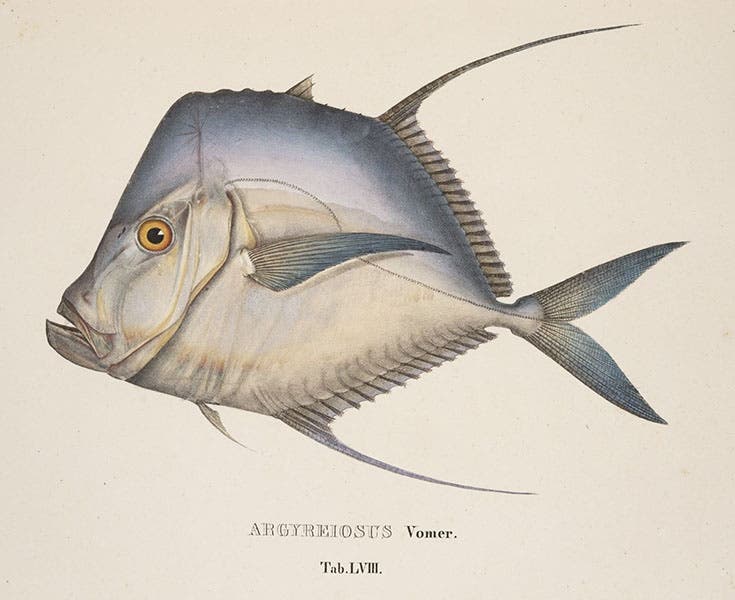

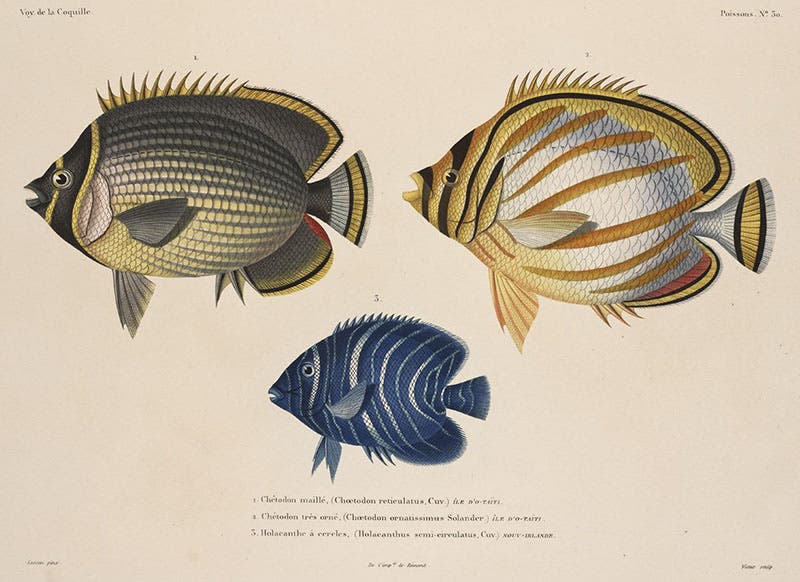

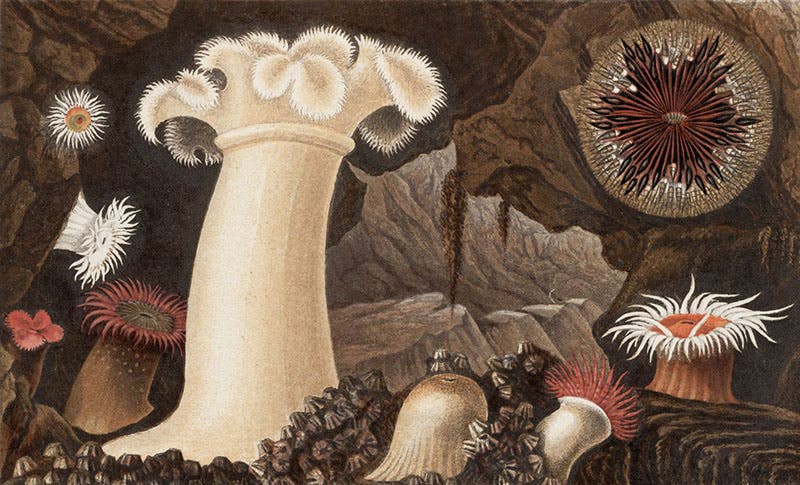

Finally, since this is a poem about a scientific subject, and since reading it evokes imagery, I thought I would include several illustrations of fish and the briny deep from our history of science collection, images that always come to my mind when I read The Fish. I wanted to use more, but the text of the poem is not easily interrupted – there is only one stanza that ends with a period (and I inserted an anemone image there). Otherwise, the images have to come in this introduction, or at the end.

Here is Moore’s poem. Note that the title is also the first line of the poem.

The Fish

wade

through black jade.

Of the crow-blue mussel-shells, one keeps

adjusting the ash-heaps;

opening and shutting itself like

an

injured fan.

The barnacles which encrust the side

of the wave, cannot hide

there for the submerged shafts of the

sun,

split like spun

glass, move themselves with spotlight swiftness

into the crevices—

in and out, illuminating

the

turquoise sea

of bodies. The water drives a wedge

of iron through the iron edge

of the cliff; whereupon the stars,

pink

rice-grains, ink-

bespattered jelly fish, crabs like green

lilies, and submarine

toadstools, slide each on the other.

All

external

marks of abuse are present on this

defiant edifice—

all the physical features of

ac-

cident—lack

of cornice, dynamite grooves, burns, and

hatchet strokes, these things stand

out on it; the chasm-side is

dead.

Repeated

evidence has proved that it can live

on what can not revive

its youth. The sea grows old in it.

One does not discover until the second line that “The Fish” is plural, so that justifies most reader’s mental evocation of a single fish, when we think of the poem, as in our first image of the Lookdown, one of the great fish images of all time.

I hope you agree that The Fish is a suitable topic for a history of science blog. I am sure that if it were submitted to Dava Sobel as a prospect for “Meter”, she and the magazine would snap it up.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.