Scientist of the Day - Margaret Lindsay Huggins

Margaret Lindsay Huggins, an Irish astronomer, photographer, and spectroscopist, was born in Dublin on Aug. 14, 1848. She developed an interest in photography as a young woman, and also in astronomy. The passion for photography was unusual for a woman, for in those early days it was all chemistry, and messy chemistry to boot. Exactly what she read to kindle the astronomy bug is not clear, although efforts have been made to run that down. Some think she might have read some of the work of William Huggins, an English astronomer who built an observatory on Tulse HIll in South London in the 1850s and who was soon using spectroscopy to make astronomical discoveries, such as that many nebulae have the characteristic spectra of gases, not stars, and were probably gaseous in nature, and that the spectrum of the star Sirius has a slight red shift, indicating that it is moving away from us. We make this surmise because when Margaret met William in the early 1870s, it seemed to be a match made in heaven, even though she was 24 years younger than William, and the two were married in 1875 in Dublin, and then moved back to Huggins' home and observatory in Tulse Hill.

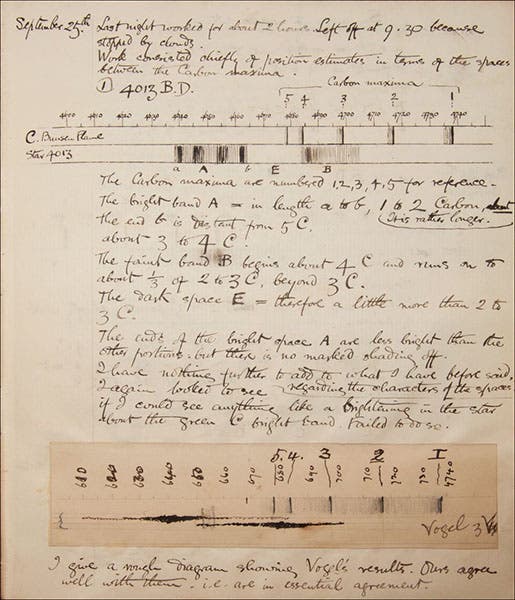

It has always been well known that Margaret worked closely with William in all his endeavors, and brought to their collaboration considerable expertise of her own. But it has generally been assumed that the working relationship was that of master-assistant, with Margaret being the assistant. However, recent work by Barbara Becker has shown otherwise. After William died, Margaret gave some of her scientific memorabilia (fourth image) to the Whitin Observatory at Wellesley College in the United States, including all her lab notebooks (fifth image). Professor Becker took a close look at the notebooks, and at Margaret’s surviving correspondence, and discovered that the Huggins’ partnership was very much one of equals. Margaret knew much more about photography, and seems to have convinced William of the value of astrophotography for their spectroscopic work, and introduced him to new techniques. She laid out many of the investigative agendas that the two pursued, and kept the records. She shared the observations with William for their major publication, An Atlas of Representative Stellar Spectra from 4870 to 3300 (1899), where she is listed as coauthor.

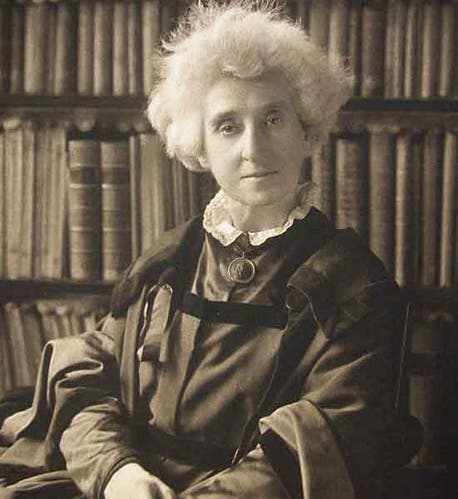

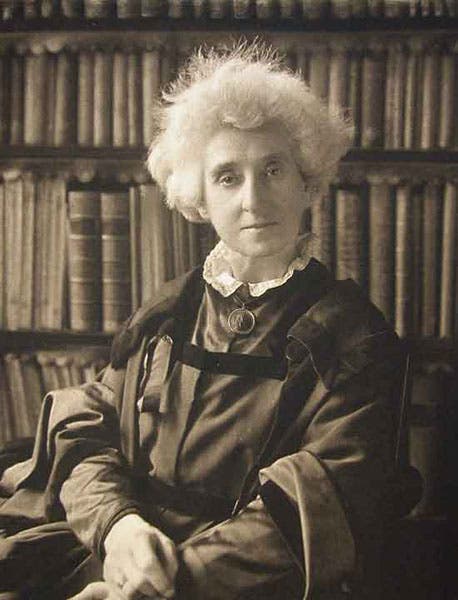

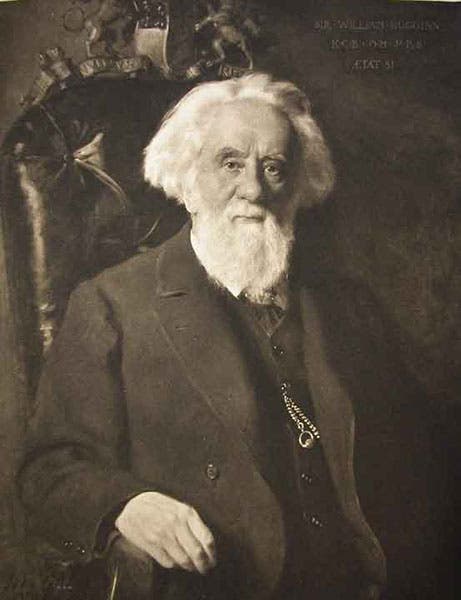

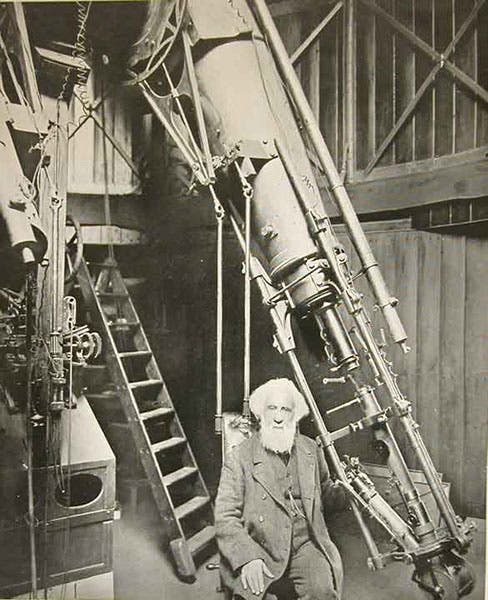

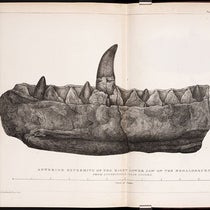

It is easy to get the wrong impression of Margaret’s role from the collection of William’s scientific papers that she published in 1909, and that we have in our collection. It is called The Scientific Papers of Sir William Huggins, and it is a beautiful volume, with 66 plates, many full-page. When you open that book, there is a frontispiece portraying William (second image), then a second frontispiece portraying Lady Huggins (first image), and then a third showing William, and only William, at work at the Tulse Hill telescope (third image). But that was just Margaret playing the necessary Victorian game, yielding the spotlight to her husband and declining to highlight her own contributions. Yet is clear from many remarks that Margaret made, for example, when she was awarded a pension after William’s death, that she considered herself a fully equal partner in the entire Huggins’ enterprise. And there is now no reason to doubt that she was just that.

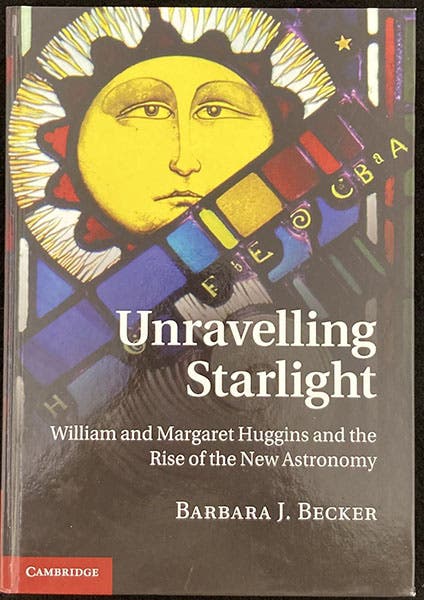

Barbara Becker published the results of her research on William and Margaret Huggins in several journal articles, and then in a book. Unravelling Starlight: William and Margaret Huggins and the Rise of the New Astronomy (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2011). We have this book in our open collections. The printed cover shows a stained-glass window that Lady Huggins presented to the Whitin Observatory at Wellesley College in 1914, which features the Sun, its corona, and the solar spectrum with its Fraunhofer lines (sixth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.