Scientist of the Day - Margaret Hamilton

Margaret Heafield Hamilton, a software systems engineer, was born Aug. 17, 1936. Hamilton attended Earlham College in Indiana, and then came to MIT in 1959, where she worked in the lab of Edward Lorenz and helped develop software for weather prediction, at the very time Lorenz was discovering the Butterfly Effect and laying the foundation for Chaos Theory. At another laboratory at MIT, Lincoln Lab, she then wrote software for one of the country’s first air defense systems, the SAGE system. By 1968, she was working in the MIT Instrumentation Lab, developing software for the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC), the world’s first portable computer, which would be carried aboard the Apollo Command Module and Lunar Lander (LEM). The lab was run by Charles Stark "Doc" Draper. In our profile of Draper some years ago, we discussed the AGC, but did not mention the software. I do not know when software development began for the AGC – it would seem that Hamilton would have been late to the table in 1968 – but she had time to display enough talent that she was soon in charge of software development for the AGC.

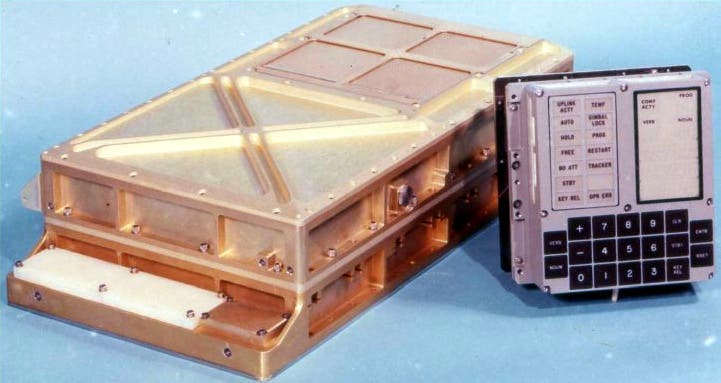

Those of us who are not software engineers cannot appreciate what makes a good one, or what special gifts Hamilton brought to the Apollo program. One important contribution seems to have been the conviction that every possible problem had to be anticipated by the software. If someone punched the wrong button on the DSKY (the small keyboard computer interface that the astronauts used; third image), the computer had to respond without crashing. One thing she planned for, which turned out to be very important on the Apollo 11 landing, was the possibility that the computer might be overloaded with tasks (the AGC had a very tiny RAM memory). She devised something called the Priority Display, which the computer would flash on the DSKY to warn that the processor was being overwhelmed and the computer would attend only to matters relevant to the task at hand, such as landing the LEM. Just such a situation occurred on the Apollo 11 landing, and the MIT experts at Mission Control were able to assure the flight director that there was no need to abort the landing – the computer was doing that job properly and ignoring everything else.

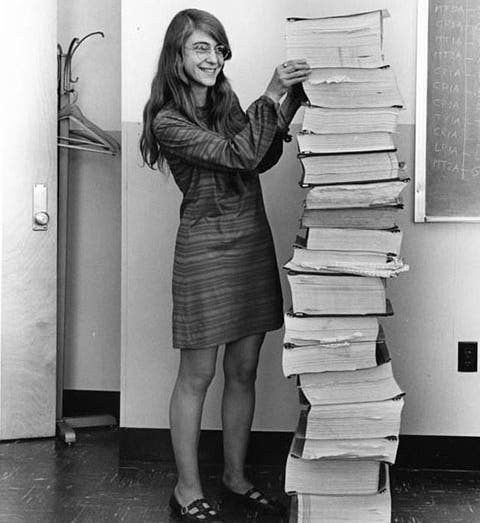

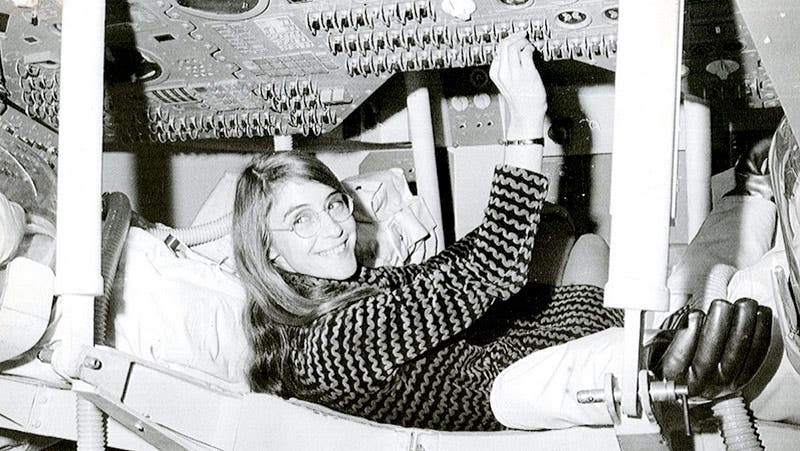

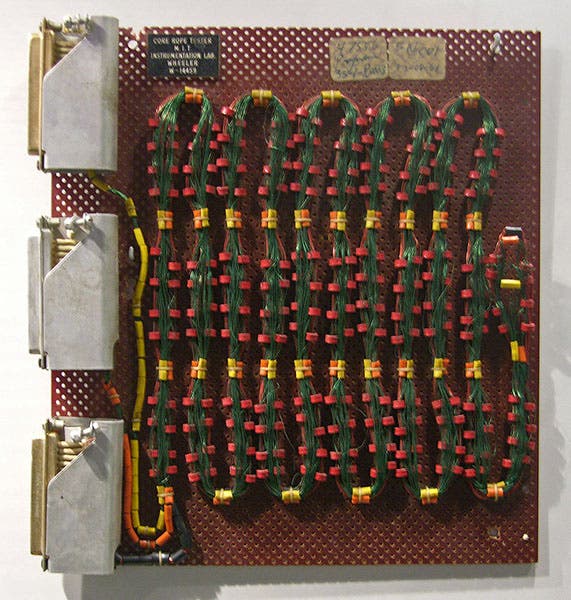

There is a famous photo that shows Hamilton in 1969 at MIT, standing next to a stack of Apollo code books as tall as she was (first image). I suspect that the publicity stunt bent the truth a little, for the programmers who manned the MIT action room the day of the Apollo 11 landing and wrote accounts of the crisis, mention that their code books were 6 inches thick, not 60. But one can see why the photo is so popular. Another shows her in a LEM pilot seat, or perhaps a simulator, where I doubt that she spent much time either (second image). But it is just as beguiling as the code-books photo. And we thought we would also show where Hamilton’s programs for Apollo resided, the “rope memory”, where the software was literally hard wired into place (fourth image, below).

Hamilton is also credited with inventing the term “software engineering” and using it during her Apollo years, beginning in 1968. When she started writing software, there was no profession to describe what she did, and no schools for software system design. That all changed, and very quickly, due to the efforts of Hamilton and others.

Margaret Hamilton is world-famous today, and she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Obama in 2016 – the last such medal he conferred. But I found in researching this piece that Hamilton is hardly mentioned in the literature before 2016. I own two books on the subject at hand, one that is a history of just the AGC, and another on the larger topic of computing and the Apollo program, written in 1996 and 2008 respectively. The first work does not even mention Hamilton; the second, only three times, and very briefly. Clearly something has happened in the past five years to bring Hamilton to national attention. Perhaps it was just the rising power of the voices of women scientists on social media, calling attention to their own. A more specific cause has been suggested – the infamous #HackAHairDryer ad campaign of IBM, launched on Dec. 6, 2015, in which IBM suggested that women might be attracted into STEM fields if they were allowed to design hairdryers. A twitter firestorm followed, and Margaret Hamilton was often mentioned in tweeted responses as someone who was getting us to the Moon and had little time for hairdryers. IBM pulled the ad the next day, and 11 months later, Hamilton was famous enough to be shaking President Obama’s hand. It was an ascent to prominence that was well deserved. Not only has she had a splendid career, but she is a wonderful role model for young women who are contemplating scientific careers.

In 2019, Google set out to honor Margaret Hamilton and all software engineers by programing over 100,000 mirrors at a solar observatory in the Mojave Desert to paint a portrait of Hamilton, using the light of the moon. The resulting optical marvel was over one mile square. There is a one-minute video, called Margaret by Moonlight, that records the event, and it is just marvelous.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.