Scientist of the Day - Marc Isambard Brunel

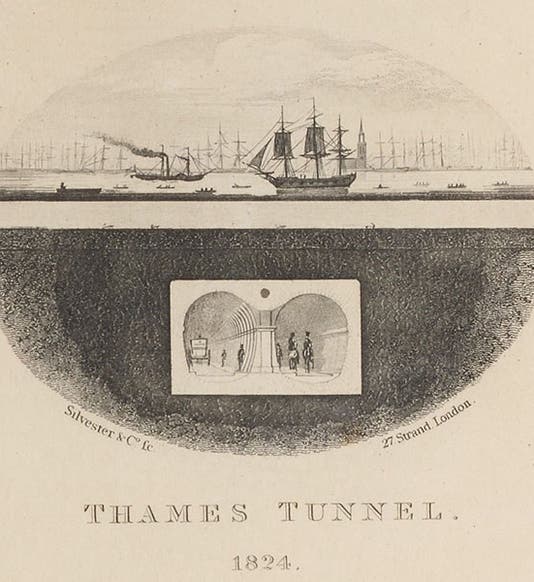

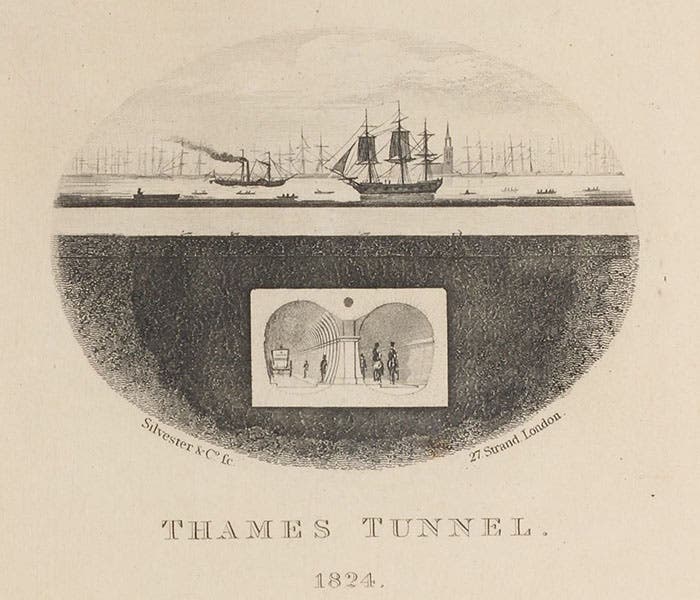

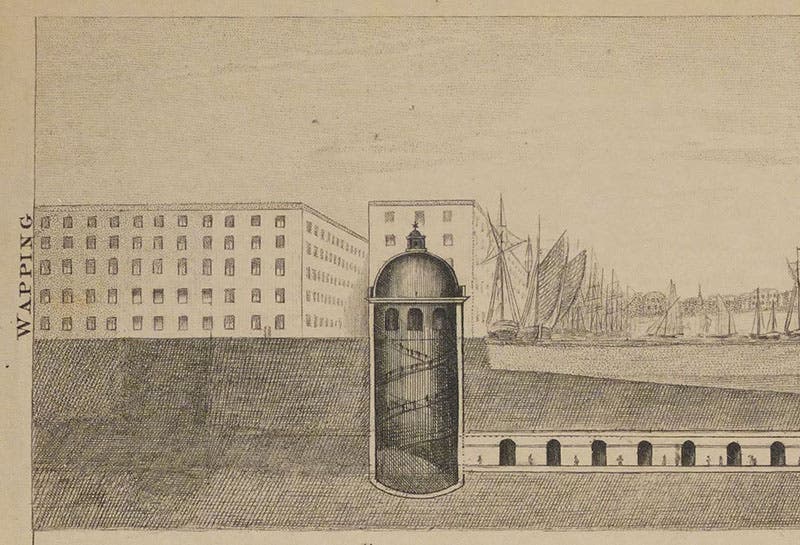

Marc Isambard Brunel, a British civil and mechanical engineer, was the first man to successfully supervise the digging of a tunnel under a navigable river, in this case, the River Thames at the London docks. The digging of the Thames Tunnel was made possible by Brunel's invention of a device called a tunnelling shield, which provided a stage at the front end of a tunnel shaft for 36 miners to remove a few inches or so of earth, before advancing the shield to have a go at another bit of clay or sand. The tunnel began with the sinking of an entrance ramp caisson in Rotherhithe, on the south side of the Thames, and then advancing horizontally under the river toward Wapping on the north bank. Work began in 1824 and progressed steadily until 1827, when the river bottom broke through and flooded the tunnel. Although the breach was plugged with sandbags, another breach in 1828 caused the project to be shut down.

We told the story thus far in a post exactly three months ago, with illustrations from a book, Sketches of the Works for the Tunnel under the Thames, from Rotherhithe to Wapping (1828), which was sold at the site to onlookers who paid one penny to wander into the tunnel and check on progress. We promised to finish the story in a future post, and here we fulfill that promise. You might want to read the earlier post again, since it has images that we will not repeat here.

The government had funded the initial dig, with considerable help from individual subscribers, but no more support was forthcoming until late in 1834, when an additional £247,000 was provided, and the digging recommenced in 1836, with Brunel still in charge, after a lapse of 8 years. The pamphlet of 1828 was reprinted in 1836 and sold on site, with a new title: An Explanation of the Works of the Tunnel under the Thames. There must have been an abundance of French tourists, for the Thames Tunnel Co. also commissioned a French edition from their London publisher. We have both 1836 editions in our collections, as well as a later 1839 French edition, and then an “18th edition,” printed in 1856, long after the tunnel was completed in 1843. They differ from each other in interesting ways.

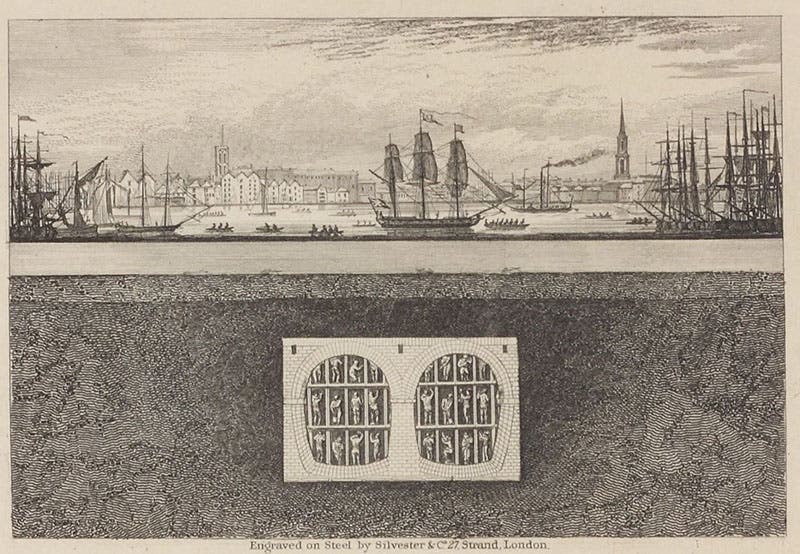

The 1836 English edition is large, for a tourist guide, so that the tiny engravings from the 1828 edition are surrounded with wide margins (which we have cropped off here). In the French edition that same year, with the same engravings, there are hardly any margins, and the entire publication would easily fit in your pocket. Both editions have new engravings, in addition to repeating some of those of 1828.

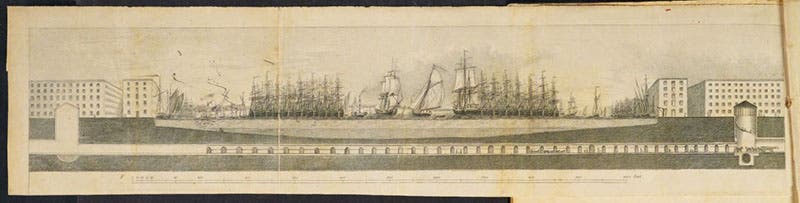

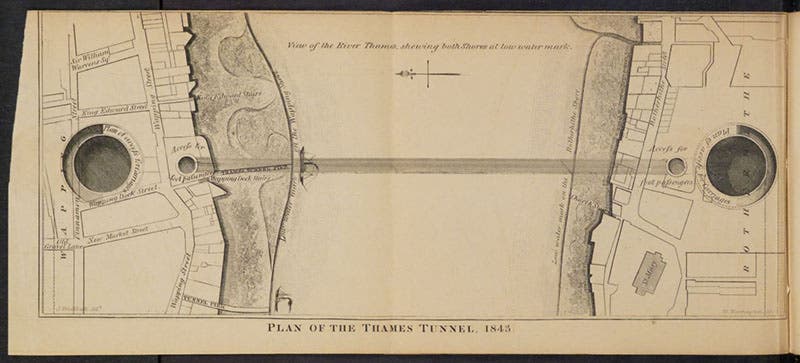

All four of the editions have a long folding map that shows a cross section of the Thames and a longitudinal section of the tunnel. Interestingly, in the 1st edition of 1828 (see our first post), the section shows the tunnel as if completed. In the 1836 editions, the tunnel is show as finished only from Rotherhithe to river center (fourth image); in the 1839 edition it is shown as three-fourths completed (eighth image), and then in our “18th edition,” it is once again, but now properly, depicted as a completed tunnel. In all these versions of the long section, the tunnel is depicted as flat. In truth, it sloped down rather steeply toward the center, and then back up again.

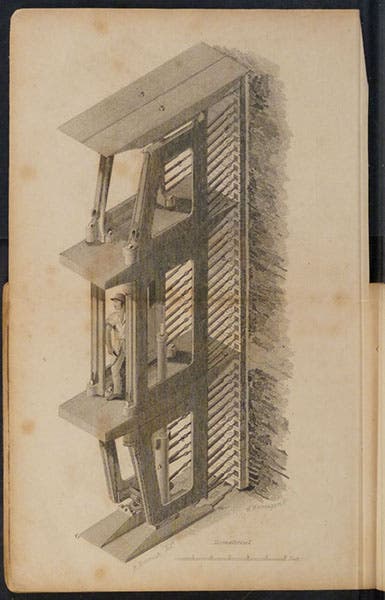

The 1836 English edition includes a plate that shows one frame of the 12-frame shield, with three levels, each including a miner. It fits easily on the page. In the French edition of that same year, it has to be a folding plate, which, interestingly, folds upward (seventh image). Each of these frames, by the way, weighed 7 tons. The shield in use from 1836 on was a new one, larger and sturdier and easier to keep in alignment. The old one, now rusty, had to be broken down and hauled out through the completed half-tunnel in pieces, to be sold for scrap, before the new one could be installed. There are no images of this arduous process.

The progress of digging the tunnel was now steady from 1836 on, but frought with difficulties, such as leaks and cave-ins that often halted the project, and led to steady criticism of Brunel from the press, which made his life difficult. Brunel often spent 18-hour days at the dig, and the stress was so great that at one point he suffered a mild stroke. But he recovered, and was able to accept a knighthood in 1841, when it finally became evident that the tunnel would be completed, which it was in 1842.

The grand opening was Mar. 25, 1843, when hundreds of thousands of Londoners gathered at Rotherhithe, paid one penny, and walked 1300 feet to Wapping, and then back. The two tunnels were connected along their length by archways, and each arch held souvenir peddlers, who did brisk business that day, and would for years to come.

Detail of the long folding cross section engraving from the 1856 ed., showing how the location of the Wapping carriage caisson has been burnished out of the copper plate, An Explanation of the Works of the Thames Tunnel now completed from Rotherhithe to Wapping, 18th ed., by the Thames Tunnel Co., 1856 (Linda Hall Library)

The original intention was to build two large entrance ramps beyond the pedestrian ramps that would accommodate horses and carriages (ninth image). But Brunel was never able to get funding from the government to build those ramps, which would have been expensive, and they never were constructed (tenth image). The Thames Tunnel remained a pedestrian walkway, and a curiosity, until the East London Railway Co. bought it in 1865 and laid down tracks for trains. The tunnel served well as a railway tunnel, and indeed it still does. The masonry, which Brunel’s crews installed so carefully, has never cracked or leaked, even though it has no iron reinforcement. Brunel had done his work well.

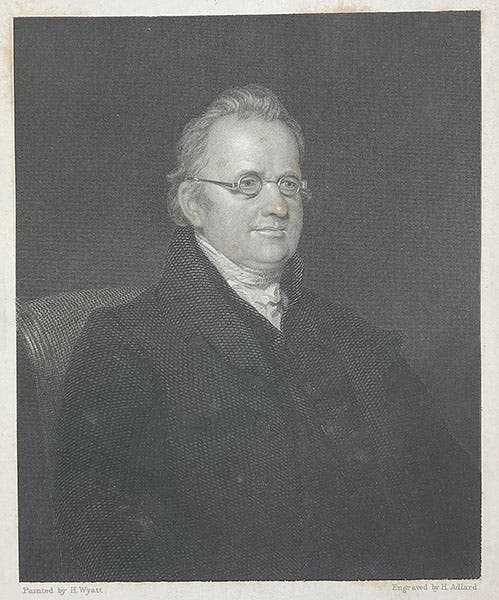

One of Brunel’s engineers for most of the construction was Richard Beamish, who wrote a biography of Brunel, published in 1862. The frontispiece is an engraved portrait, made after the painting we showed in our first Brunel post, which we use here as our second image.

Brunel died on Dec. 12, 1849, at the age of 80, and is buried in Kensal Green Cemetery in London. He would be joined there just 10 years later by his son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.