Scientist of the Day - Marc Isambard Brunel

Marc Isambard Brunel, a British mechanical and civil engineer, was born Apr. 25, 1769. Brunel was the father of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who built the Great Western Railway and the steamships Great Western and Great Eastern, and since the son went by the name Isambard, we tend to call Marc Isambard “Marc Brunel,” although he too actually went by the name Isambard during his life.

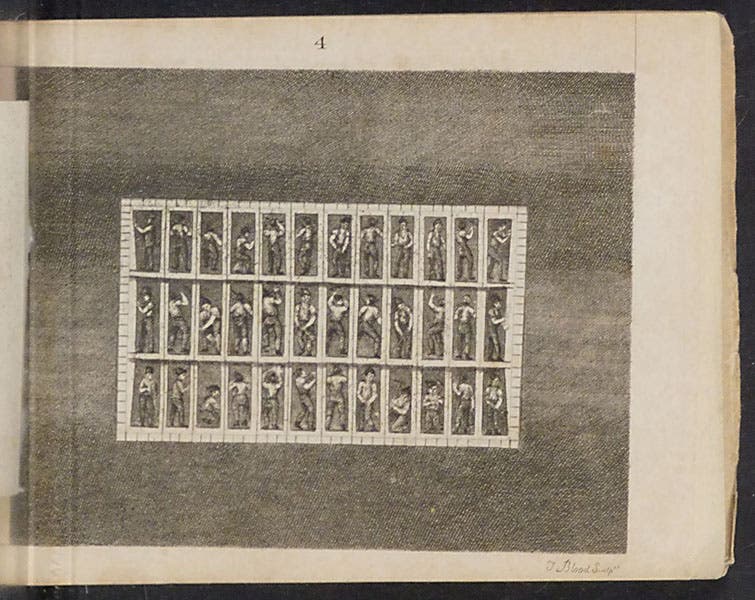

Marc Brunel is best known for designing, executing, and persevering with the Thames Tunnel, the first tunnel ever built under a navigable river. The tunnel is 1300 feet long and lies 100 feet below the surface of the Thames River, and it took 18 years to complete, with work starting early in 1825 and the tunnel finally opening on Mar. 25, 1843.

We are going to tell the story of the building of the Thames Tunnel in several stages, because we have quite a few contemporary publications, rich in imagery, that document the building of the Thames Tunnel., and it is best to discuss and show illustrations from just one work at a time. We begin today with a small pamphlet titled: Sketches of the Works for the Tunnel under the Thames, from Rotherhithe to Wapping, published in 1828, when the tunnel project had just been shut down, as we shall see.

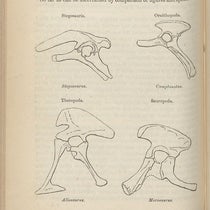

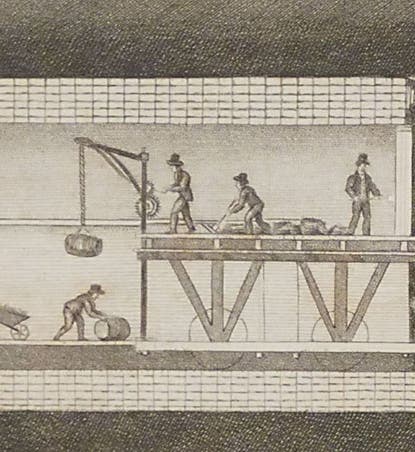

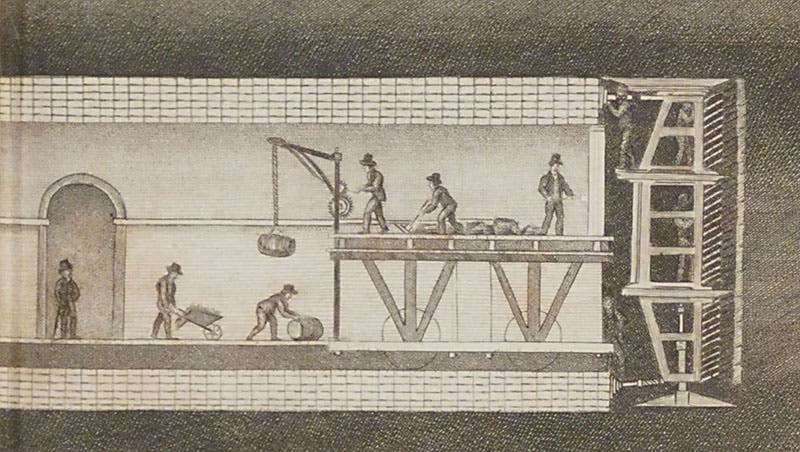

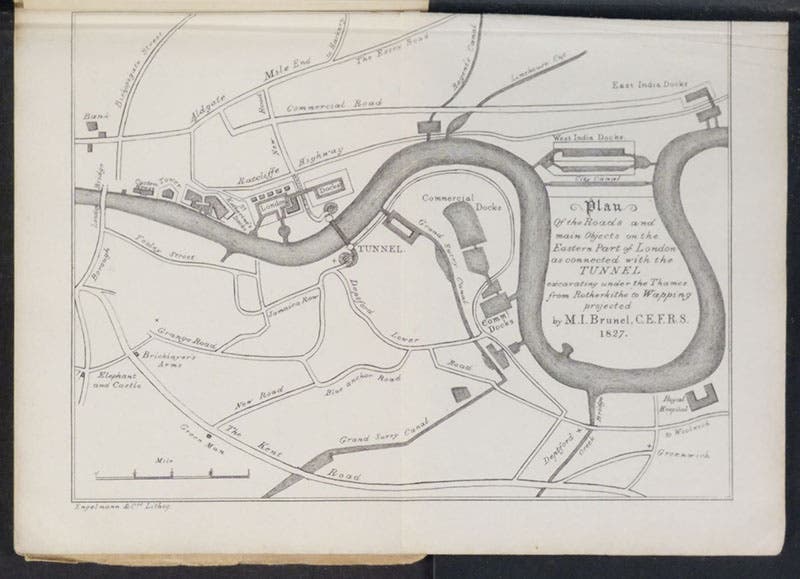

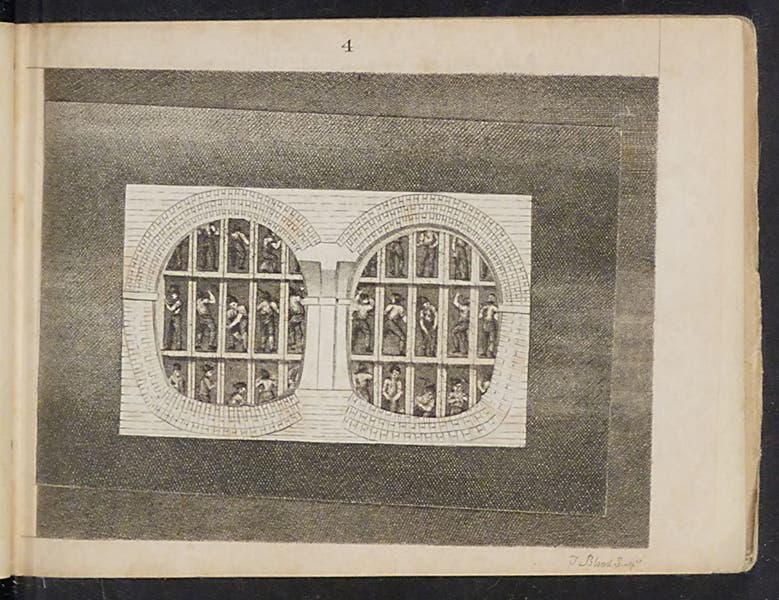

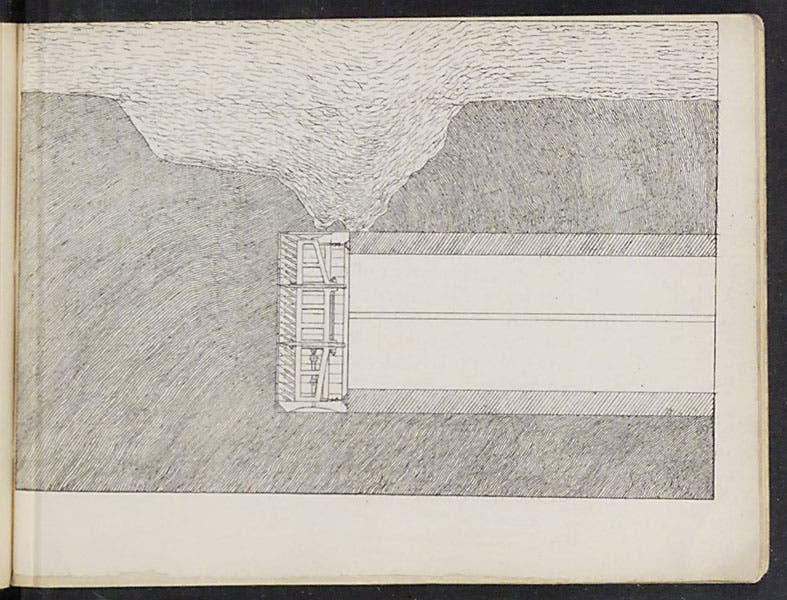

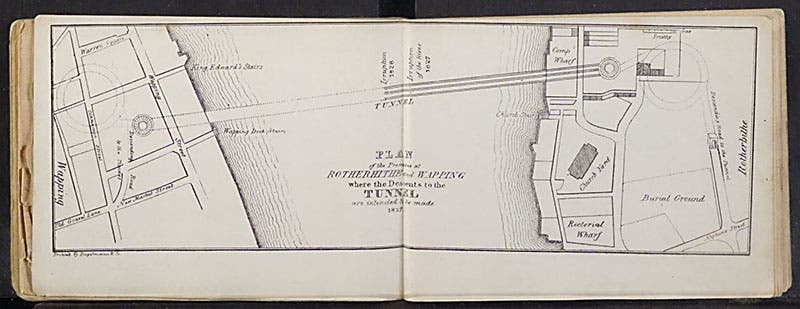

An attempt to construct a tunnel below a river was made possible by the invention of the “tunneling shield” by Marc Brunel. The shield, which was built by Henry Maudslay, was a cast-iron frame, containing 12 vertical sections with a total of 36 separate compartments, allowing 36 excavators to remove a foot or so of earth from each compartment. When the accessible dirt had been removed, the frame was advanced by screws, and bricklayers came in behind to seal in the tunnel with masonry (first image). It was a slow but steady process. Large cylinders with ramps were built into the ground at each end, connecting the tunnel to the surface; the right (south) side in most of the llustrations here is Rotherhithe, and the left (north) is Wapping.

The digging went well until they had nearly reached the middle of the Thames, where the river was deepest, and the river bottom was closest to the advancing shield. On May 18, 1827, water came pouring through the shield and filled the entire tunnel. Digging was being supervised at this point by Brunel's son, Isambard Kingdom. He used a diving bell to examine the damage, and eventually the cavity where the river bottom had been scoured out was filled with sandbags, so digging could recommence in 1828. But another leak occurred in 1828 (this one nearly drowning Isambard junior), and the tunnel was shut down and work was suspended indefinitely by the director, William Smith. Smith (with whom Brunel never got along) was finally removed and replaced in 1833, and the project was started up again, but that is a story for another time.

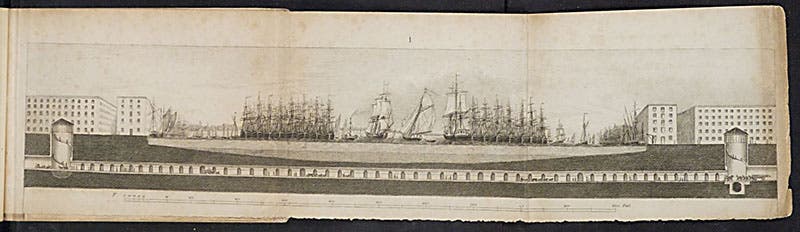

Our little pamphlet has a variety of illustrations (the text is rather perfunctory). In addition to the section showing the shield at work (first image), there is a map of downtown London, showing where the tunnel was being built (fourth image), and a long folding section across the river, depicting how the tunnel would appear when completed, the most striking feature of which is the flotilla of ships anchored above (fifth image).

One plate, an end-on view of the advancing tunnelling shield, has a fold-back element; the fold-back is a template of the tunnel, and when it is in place, you can barely see the shield through the tunnel openings (sixth image). Fold it back, and you can see the shield in full operation, with all 36 miners hard at work (seventh image).

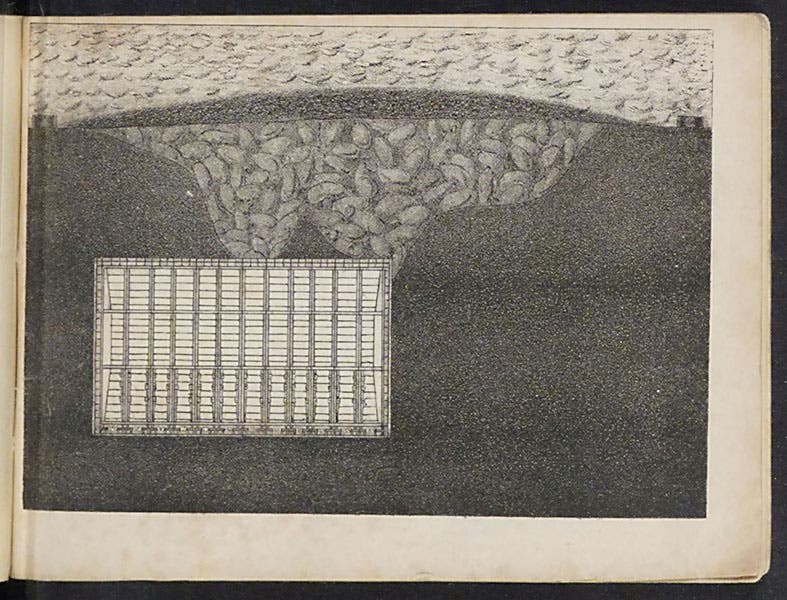

Another section shows the shield at the point where the water broke through on May 18, 1827 (eighth image). A follow-up engraving shows the same section later, after the leak had been plugged up with sandbags (ninth image).

A final, bird’s-eye view of the river crossing shows how far the tunnel had advanced when a second leak occurred, and the tunnel was shut down indefinitely (tenth image). Construction would not resume until 1834.

We have several more pamphlets on the Thames Tunnel project, published in 1836 and 1838, that document the second stage of tunnel building, with illustrations that are just as delightful as the ones here. We will pick up the story later. We will place a link here when the next installment is published.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Columbine, hand-colored woodcut, [Gart der Gesundheit], printed by Peter Schoeffer, Mainz, chap. 162, 1485 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/3829b99e-a030-4a36-8bdd-27295454c30c/gart1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)