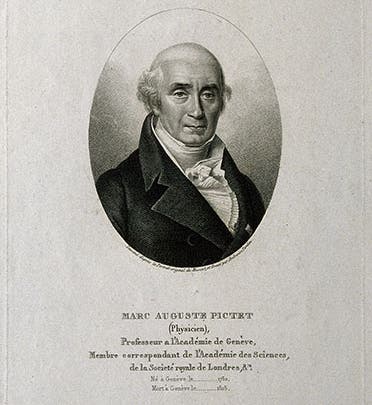

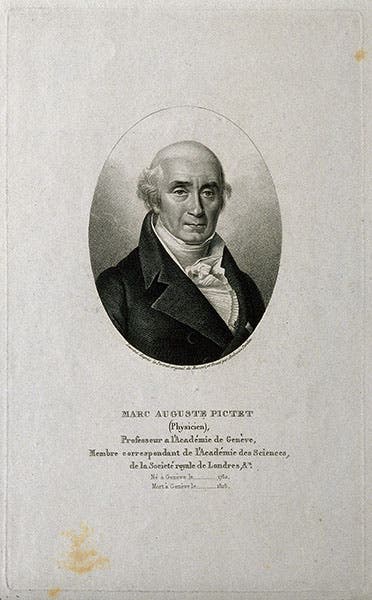

Scientist of the Day - Marc-Auguste Pictet

Marc-Auguste Pictet, a Swiss chemist, natural philosopher, and scientific translator, was born in Geneva on July 23, 1753. He was not much of an original scientist himself, but he was instrumental in disseminating the physical and chemical discoveries being made in England by the likes of Count Rumford, Humphry Davy and James Hall, to the French-speaking world. England in the early 19th century was having its own chemical revolution, with the frequent discovery of new elements, and the development of electrolysis as an indispensable chemical tool, and Pictet was the one who made their work known on the Continent . He helped found the Geneva Society of Physics and Natural History in 1791, and one of the first things the Society did was start up a journal, the Bibliothèque Britannique, whose purpose was to publish translations of the latest English scientific papers (second image). Pictet was the editor of the science part of the journal, did most of the translating himself, and quite often published original scientific papers that had been sent directly to him.

For example, when Jean-Baptiste Biot determined that the l'Aigle stones that fell in France were meteorites that came from space, he announced that conclusion in the Bibliothèque Britannique, vol. 23, 1803, and we showed a page from that journal in our post on Biot. William Thomson published the first image of a Widmanstätten pattern, which appears on the face of a meteorite (and only on a meteorite) when it is subjected to acid, in vol. 25 of the Bibliothèque Britannique, published in 1804, and we showed this woodcut in our post on Thomson. François Huber, the blind apiarist, wrote several letters to Pictet about his work on honeybees, which we did not mention in our post on Huber.

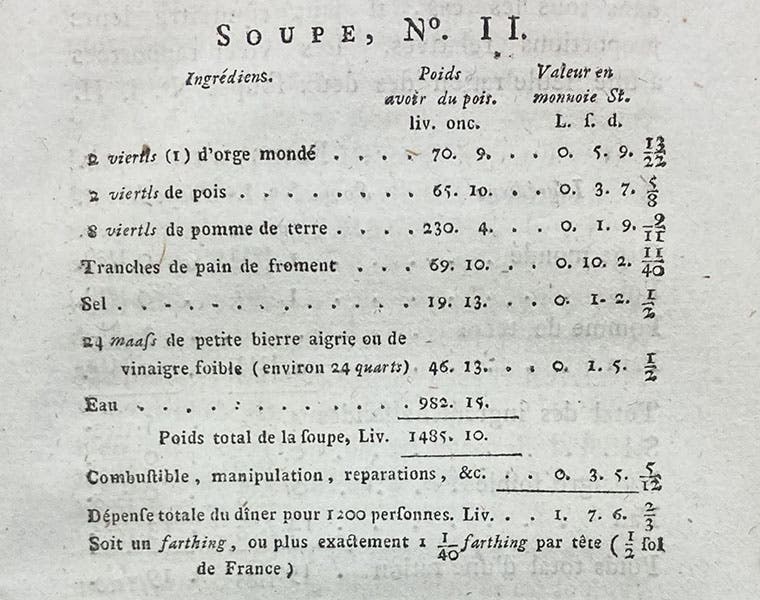

I could not find a list of important papers published in the Bibliothèque Britannique in the 20 years when Pictet was its scientific editor, so I just pulled vol. 1 off the shelf and took a look. There were several articles by Count Rumford (Benjamin Thompson) on heat that Pictet translated, including one that included a recipe for the famous “Rumford soup” that Rumford devised to feed the Bavarian army in Munich. I show it to you here – orge is barley, pois are peas, pomme de terre are potatoes, and pain is bread – with the advisement, should you want to try it out, that the recipe makes 1485 pounds of soup, feeding 1200 soldiers (third image).

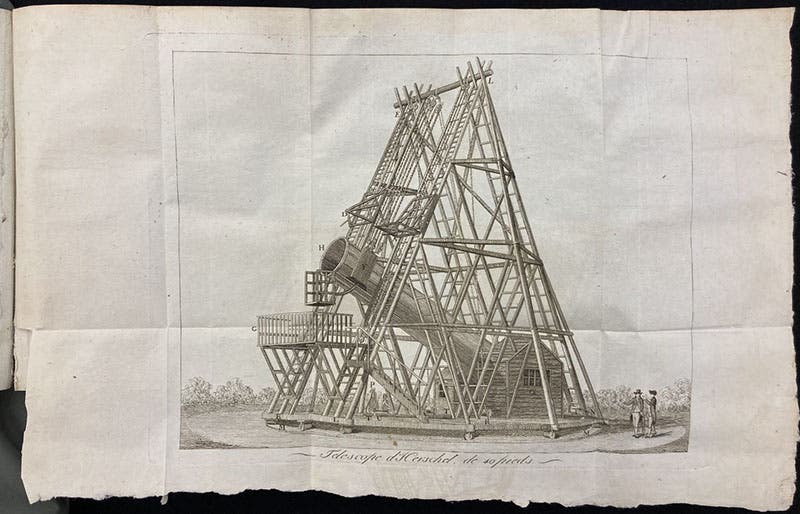

Also in this first volume is a short article on William Herschel’s 40-foot reflector, with an large fold-out engraving (fourth image), and a short review of John Smeaton’s book on the Eddystone lighthouse, with another fold-out engraving (fifth image).

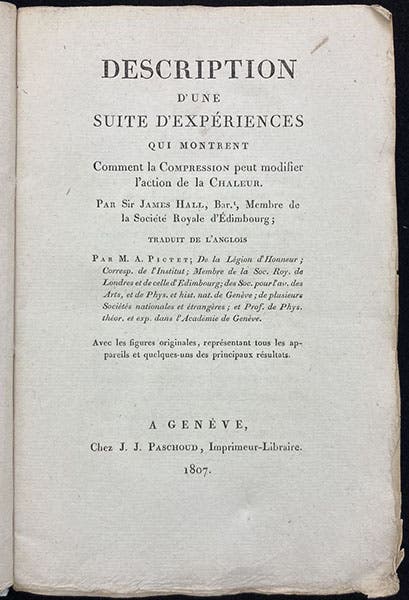

Pictet also publish book-length translations of English scientific works, of which we have two in our library, one by Count Rumford that includes 4 essays on heat that Pictet translated, and another by James Hall, published in 1807. We show both title pages here – there are no illustrations in either book (sixth and seventh images).

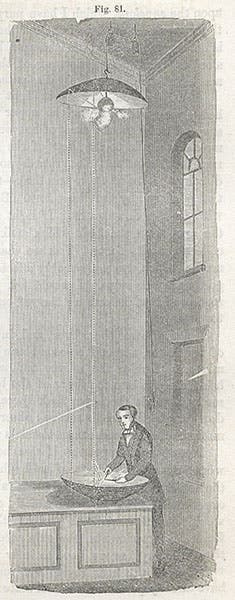

Pictet was a good friend of Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, climbed Mont-Blanc with him on one occasion, and succeeded him at the Geneva Academy as professor of natural science. One of the experiments he did with Saussure has become famous enough that it goes by his name today, Pictet's experiment. He found that if you put something cold, like ice, at the focal point of a reflecting mirror, and a thermometer at the focus of another mirror, and lined up the two at the right distance, then the mercury in the thermometer went down when the ice was inserted. It seemed as if cold was being reflected just like light or heat. Count Rumford was very impressed by this experiment and gave it its name. It works just as Pictet said, and surprises many modern physicists, who know that cold is not a “thing”, but rather the absence of heat, and they have to think about it to explain it. But it can be explained. A wood engraving in John Tyndall’s Heat Considered as a Mode of Motion (1865) is often used to illustrate Pictet’s experiment, which Tyndall did perform, but the illustration actually shows him reflecting heat, not cold, to burst some balloons up above (eighth image)

Pictet died on Apr. 19, 1825. The Marc-Auguste Pictet medal is awarded every year by the Geneva Society of Physics and Natural History for excellence in history of science, which is a nice way to remember someone who was not a historian of science, but whose work by its nature contributed greatly to modern history of science.

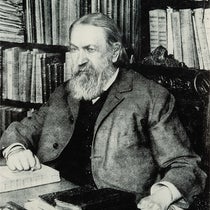

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Title page, Memoires sur la chaleur, by Count Rumford [William Thomson], tr. by Marc-Auguste Pictet, 1804 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/aecb0a83-7050-447b-9804-1f8f90271afc/pictet6.jpg?w=389&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)