Scientist of the Day - Macedonio Melloni

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Macedonio Melloni, an Italian physicist, was born Apr. 11, 1798. In 1800, William Herschel discovered infrared radiation, by demonstrating that there existed some invisible rays beyond the red end of the spectrum that would heat up a thermometer. He called it "radiant heat." For the next 20 years, no one did much with the discovery, because sensitive instruments to detect the infrared were lacking. But in the early 1820s, Thomas Seebeck, an Estonian, discovered the thermoelectric effect: if two dissimilar metals were in contact at their tips, and if the points of contact were at different temperatures, then a current would flow in the metals. An investigator in Italy, Leopoldo Nobili, built a detector based on this principle; it consisted of a stack of metallic bars, alternating bismuth and antimony, connected to a galvanometer. If one end of the stack were pointed at a heat source, a current would flow that would be detected by the galvanometer.

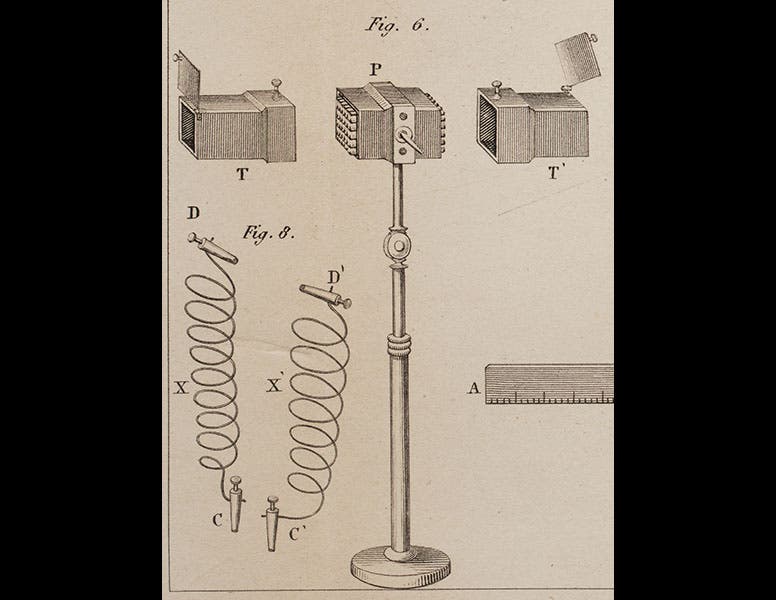

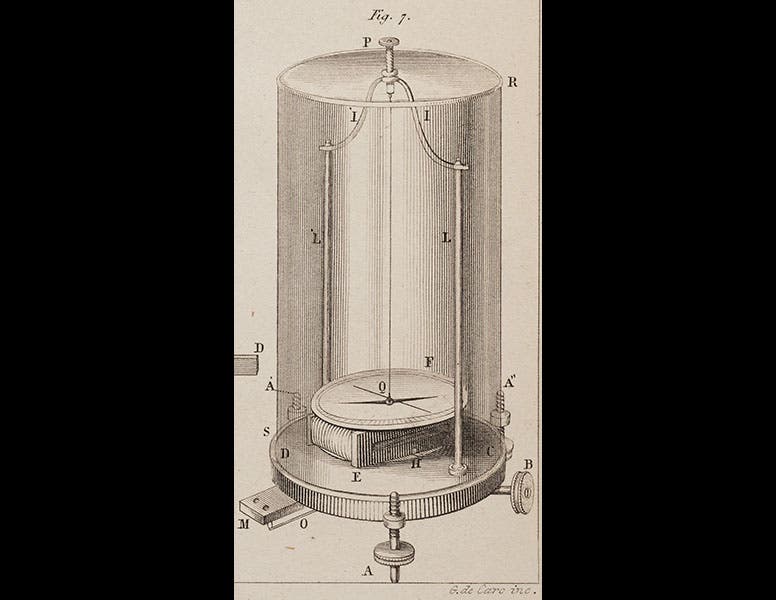

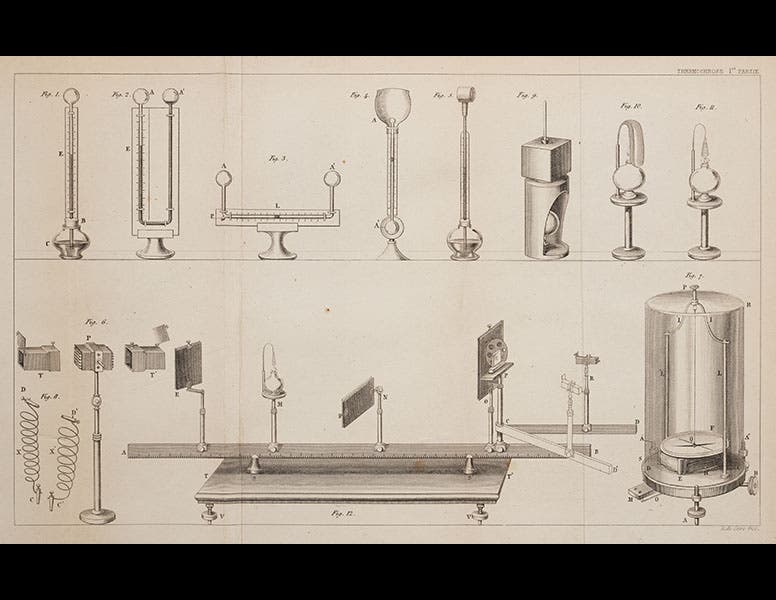

Nobili told Melloni, a colleague, about his instrument, and Melloni went to work. He constructed a much improved instrument, which he called a thermopile, or a thermomultiplier. It had a stack of metal bars, about 35 in all, connected at the ends and insulated from each other (second image). He built an improved galvanometer as well (third image). His thermomultiplier was so sensitive that it could pick up the heat of a person standing 30 feet away and could measure the thermal conductivity of all sorts of substances. Melloni did a variety of experiments in which he showed that radiant heat can be reflected, refracted, diffracted, and polarized, just like light, and he concluded that heat is a form of radiation nearly indistinguishable from light, except in wavelength. At the time (1830), most physicists still clung to what was called the "caloric theory of heat," where heat was considered to be a substance that objects acquire when heated, and emit when they cool off. Count Rumford and Humphry Davy in England had done experiments that suggested that heat was not a fluid, but nearly everyone else, especially in France, still included Lavoisier's "calorique" as one of the fundamental elements. Melloni's experiments convinced many that radiant heat is a wave, like light.

Melloni published the first volume of La thermochrôse ou la coloration calorifique in 1850, but died before he could complete the second. We have the work in our History of Science Collection, and it is the source of all the images above except the portrait. The second and third images are details from the large folding plate (fourth image). Melloni apparently coined the word “thermochrôse" in the title, which means, if you look it up: "The property possessed by heat rays of reflection, refraction, and absorption, similar to that of light rays."

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.