Scientist of the Day - Lynn Margulis

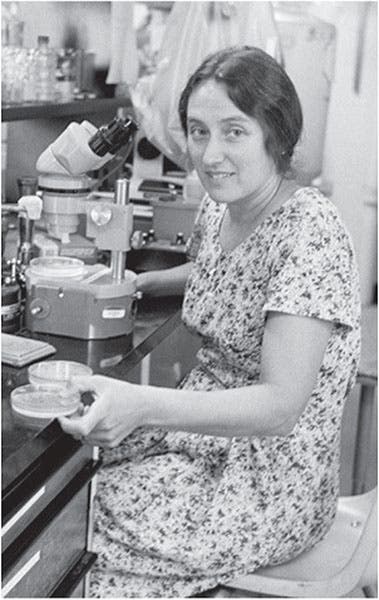

Lynn Margulis, an American biologist and geneticist, died Nov. 22, 2011, at the age of 73. She was born in Chicago on Mar. 5, 1938, and enrolled in the Lab School at the University of Chicago when she was 15. There she met fellow student Carl Sagan, five years older; the two were married when she was 19, almost on the day she graduated. The marriage lasted 8 years. She studied further at the University of Wisconsin – Madison, and the University of California at Berkeley, where she earned her PhD.

Margulis’s early interest was in cellular genetics, which wasn’t even a field in 1967, when she published her first major paper. Most people think of genes as being nuclear entities, but cellular protoplasm has genes as well. At the time, there were two known kinds of single-celled organisms, called prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Prokaryotes, such as bacteria, are very small and have no nucleus or other internal organized bodies. Eukaryotes, on the other hand, such as amoeba, and every cell in our bodies, are much larger and more complicated than prokaryotes, with a nucleus and a vast assortment of internal "organelles", such as ribosomes, mitochondria and (in the case of plants) chloroplasts.

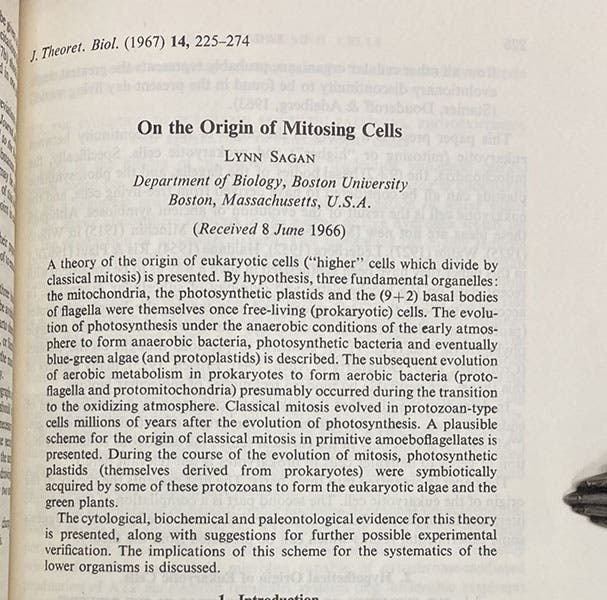

In her 1967 paper (third image), Margulis put forward the idea that eukaryotes evolved from prokaryotes by a process of symbiosis, whereby one prokaryote took permanent residence inside another, to the mutual benefit of both, gradually (over billions of years) building up more and more complicated cells. Her theory of symbiosis (sometimes called endosymbiosis (‘symbiosis within’) or symbiogenesis) was widely criticized and even ridiculed for almost 20 years – Margulis says her 1967 manuscript was rejected by 15 journals before it was accepted by the Journal of Theoretical Biology. Attitudes changed in the 1980s when it was discovered that mitochondria, the energy-making sites in every eukaryote cell, carry their own DNA and reproduce on their own, without instructions from the cell nucleus, strong evidence that they had an independent origin. Today, it is widely accepted that at least some of the cell's organelles, like mitochondria, were once independently living prokaryotes, and the theory of symbiogenesis is regarded as one of the major discoveries of 20th-century biology

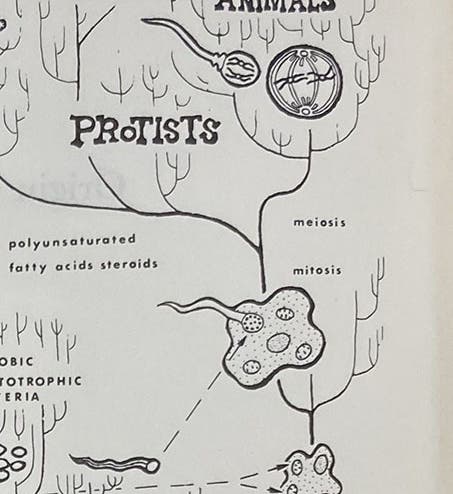

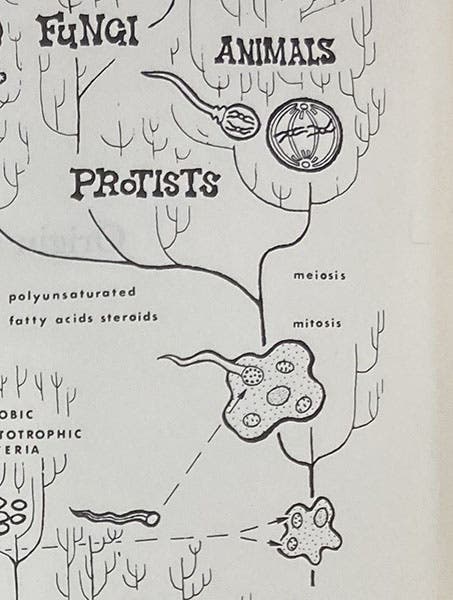

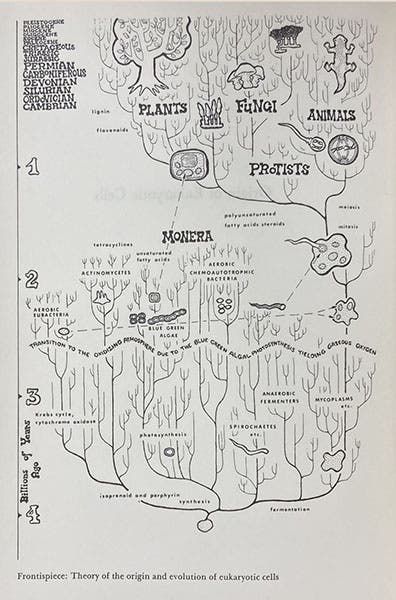

Margulis’s major monograph on the subject, Origin of Eukaryotic Cells, was published in 1970, and it began with a frontispiece diagram of symbiotic evolution. I show both a detail of the crucial moment when two or three prokaryotes gave rise to a proto-eukaryotic cell (first image), as well as the entire frontispiece (fourth image). Even though the diagram is unsigned, Margulis says in the preface that the diagrams were done by Laszlo Meszoly, so I assume he did this one. I find the frontispiece charming, stylish, and attractive, adjectives I do not often use for line diagrams. I will try to find out more about Meszoly’s work, for a possible future post. I already have one scheduled (next May 15) for another scientific illustrator I really like, Sarah Landry, who did many of the illustrations for the books of E.O. Wilson.

Margulis’s other major cause was the Gaia hypothesis of James Lovelock, in which Lovelock (and Margulis) saw the Earth as a super-organism. Since we have not yet discussed Lovelock in this forum, we will withhold discussion of Margulis’s role until we do a post on Lovelock. Meanwhile, you may read, if you wish, a 1998 book called Symbiotic Planet: A New Look at Evolution, written by Margulis just for us, where she not only recounts her role in symbiogenesis and the Gaia hypothesis, but provides a wonderful glimpse of her teen years at the University of Chicago and her fascination with Carl Sagan. Since the book has a lovely dust jacket, I show it here (fifth image), as well as a portrait of a gentler Lynn Margulis, taken when she was no longer fighting for scientific respectability (sixth image). She has that now, in spades.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.