Scientist of the Day - Luigi Ferdinando Marsili

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Count Luigi Ferdinando Marsili (sometimes Marsigli), an Italian nobleman and naturalist, was born July 10, 1658. Marsili was in some ways the Italian counterpart to Tycho Brahe, the Danish nobleman who preferred the pursuit of natural knowledge to lolling about at court. Marsili’s special interests were geology and oceanography, and he would eventually publish a Histoire physique de la mer (Physical history of the sea, 1725), which we have in our History of Science Collection, as well as a book on the Danube, which we do not have. Marsili was also a military man, and he spent twenty plus years in the service of the Holy Roman Emperor, mainly in Hungary, fighting against the Turks, even spending 8 months in captivity at one point, until he could be ransomed (second image).

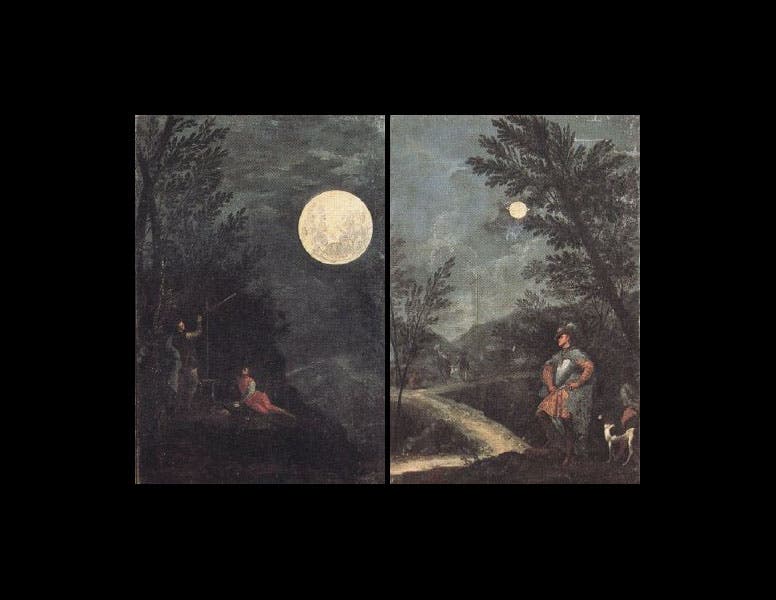

But perhaps Marsili’s greatest contribution to Italian culture was securing the establishment of the Institute of Science in Bologna, where the Count had his palace. By 1711, Marsili had collected a large number of curiosities, artifacts, and scientific instruments, and he wanted to leave them to the city of Bologna, but there was no institution to receive them, and the city was too financially strapped at the time to do anything on its own. So Marsili set out to persuade Pope Clement XI to provide the funds for a scientific institute and an observatory (Bologna was then under the joint rule of the Bolognese Senate and the Papacy). In order to convince the Pope that an institute of science was worthwhile, he did a very clever thing: he commissioned 8 astronomical paintings from a Bolognese artist, Donato Creti, each painting showing a different astronomical instrument in use, as well a view of one of the planets as seen through one of Marsili's telescopes. His idea was to present the paintings as a gift to the Pope, to show him how valuable his instruments were and what they could reveal about the universe. He even hired a miniaturist just to paint in the planets. Interestingly, he could not give the Pope a picture showing the earth as a planet, since to the Church, the earth was not a planet, the Papacy being officially geocentric at the time. So the 8th picture showed a comet instead.

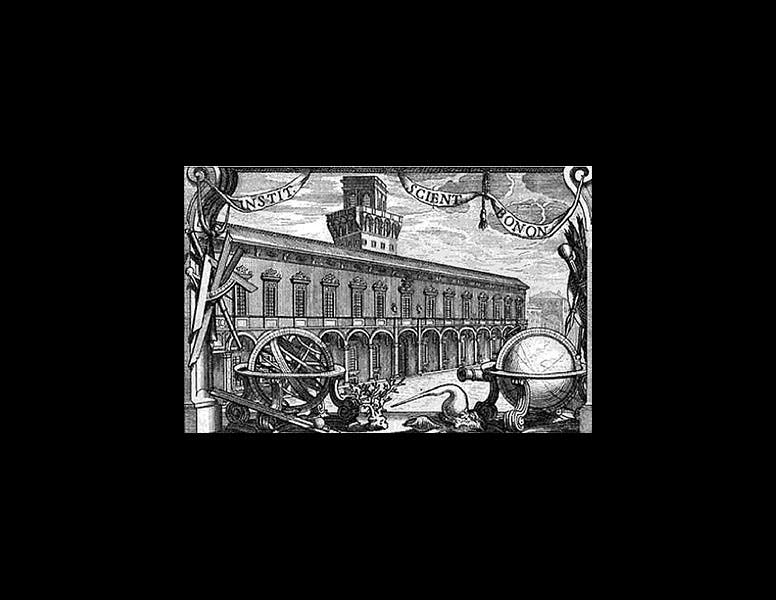

The Pope was apparently delighted by the gift (the paintings still hang in the Vatican art gallery – you can see two of them above, third image), and in 1712, he agreed to fund the Institute. The Senate chose an existing building, the Palazzo Poggi, to house it, and the Institute opened in 1715, with the Observatory being built from scratch and finally finished in 1726--the first public observatory in all of Italy (fourth image). Many notable Italian scientists were to be beneficiaries of Marsili's persistence and largess, including the astronomer Eustachio Manfredi, the Newtonian physicist Laura Bassi, and the electrical experimenter Luigi Galvani. The Institute still thrives in Bologna and is now known as the Accademia delle Scienze dell'Istituto di Bologna, the Academy of Science of the Institute of Bologna.

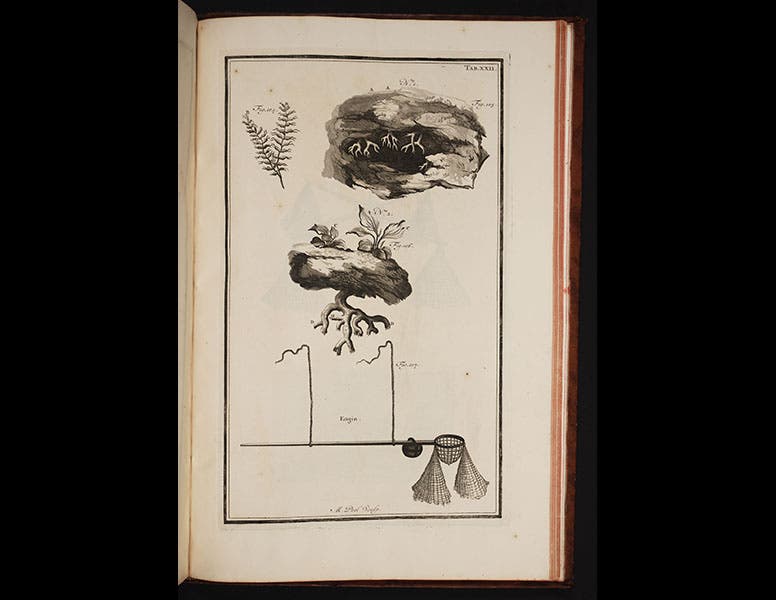

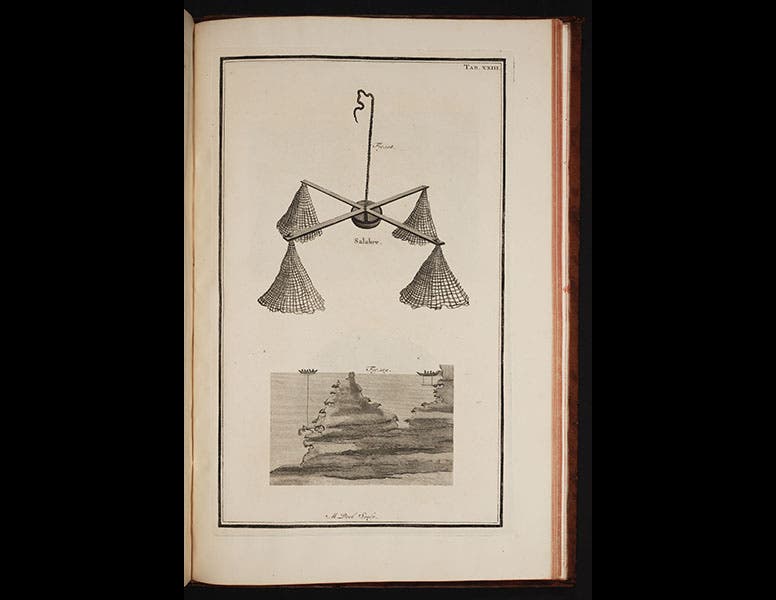

We reproduce above the title-page (seventh image) and three illustrations from the Physical History of the Sea: a detail of the frontispiece (first image), a plate showing corals growing in submarine grottoes (fifth image – these coral caves are also visible on the frontispiece), and a plate showing the use of the “engine” Marsili devised to retrieve corals from their niches (sixth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.