Scientist of the Day - Louis Sullivan

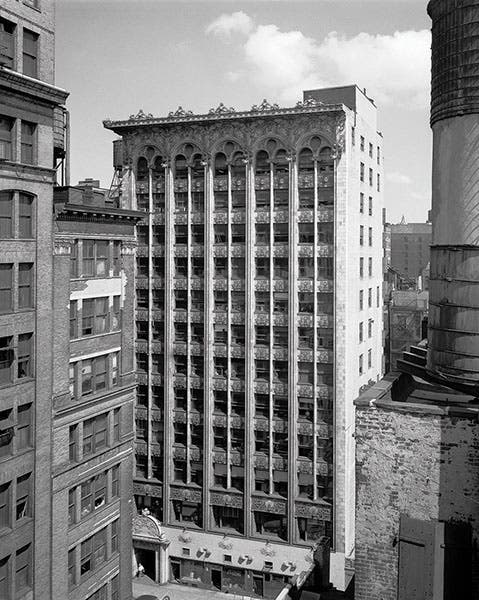

The Bayard Building, designed by Louis Sullivan, New York City, 1899, photograph by author

Louis Sullivan, American architect, died on Apr. 14, 1924, in Chicago, at the age of 67. He grew up in Boston and attended MIT briefly before moving to Philadelphia to work for the prominent architect Frank Furness. He eventually moved to Chicago after the Chicago Fire of 1871, a time of great opportunities for an architect, amidst the devastation of that event.

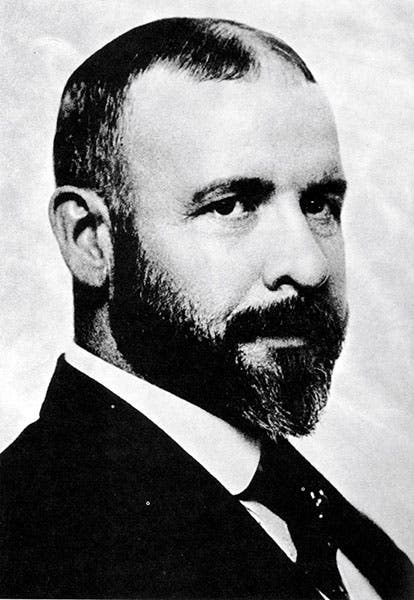

Portrait of Louis Sullivan, age 44, photograph, Burnham Library of Architecture, Art Institute of Chicago

Sullivan became not only one of the most prominent practicing architects of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but an architectural theorist who founded the Functionalist and Organic movements in American architecture. He was the mentor of Frank Lloyd Wright. Here, to highlight the significance of Sullivan, I necessarily enter what I would call the science and technology of the soul – that is, how design affects our psychological and esthetic well-being. And more specifically, how the built environment enhances (or diminishes) our emotional lives.

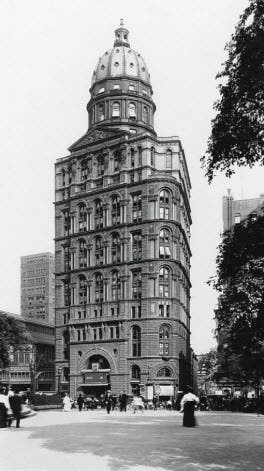

Newspaper Row building, New York City, photograph, source unknown

Sullivan’s scientific approach to architecture sought principles of design that magnified the psychological power of buildings. He aimed to identify the best ways for the built environment to be functional and also to achieve something akin to the beauty we find in natural forms. We’ll look today at only two crucial parts of his professional life: his Functionalism, and his Organic conception of architecture.

Many who are not familiar with Louis Sullivan’s life still “know” him via the famous dictum he enunciated: Form Follows Function. Here is how he introduces this idea originally, in 1896:

Whether it be the sweeping eagle in his flight, or the open apple-blossom, the toiling work-horse, the blithe swan, the branching oak, the winding stream at its base, the drifting clouds, over all the coursing sun, form ever follows function, and this is the law. Where function does not change, form does not change. The granite rocks, the ever-brooding hills, remain for ages; the lightning lives, comes into shape, and dies, in a twinkling. It is the pervading law of all things organic and inorganic, of all things physical and metaphysical, of all things human and all things superhuman, of all true manifestations of the head, of the heart, of the soul, that the life is recognizable in its expression, that form ever follows function. This is the law.

In human design (contrasted with nature’s “designs”), his principle is properly understood as aspirational – that the form of a man-made thing should follow the functions of the thing. And he introduced this idea, not merely for theory’s sake, but in an essay titled, The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered.

Detail of façade, Bayard Building, designed by Louis Sullivan, New York City, 1899, photograph by author

This was a thunderbolt thrown into the midst of the prominent architects of the time, who were flummoxed about how to design buildings arising from the new technologies of the late 19hh century – especially the introduction of steel structures and elevator systems. The impact of his form-function concept was, in architecture, analogous to the impact of Copernicus’ presentation of his heliocentric theory. Prior to his manifesto, architects thought of themselves as illusionists, attempting to hide the nature of the new technology of tall buildings by tricking viewers into thinking their buildings were short. He asserted the radical idea that a tall building should look tall; it should not visually apologize for its inherent tallness; it should celebrate its tall nature. The Bayard Building in New York City (first image) shows one of Sullivan’s solutions to the “skyscraper problem” as it was called at the time, which we might compare to what other architects were doing before his revelation, the Newspaper Row Building in New York City (third image). Architects were focused on historical styles of classic buildings that were inherently short, such as temples, palaces, churches, so they simply visually squeezed and piled temple/palace design motifs on top of one another to fake the visual reality of this new technology. We show additional details of Sullivan’s Bayard Building (fourth and fifth images), which not only celebrated its nature, but introduced the public to his new American system of naturalistic ornamentation.

Detail of façade, Bayard Building, designed by Louis Sullivan, New York City, 1899, photograph by author

This thesis about tall buildings, and more generally form following function, is an expression of his Organic approach to architecture. To be organic means, in part, to be true to the nature and function of a thing. If a building functionally must be tall, it should show that nature, not hide it; if a building needs to enclose massive space for large scale human activity, it should visually celebrate that spatial need. One of the reasons the term “organic” was used in this metaphorical way, was that everyone was intuitively familiar with the idea that animals and plants had natural forms that arose from their natures and functions.

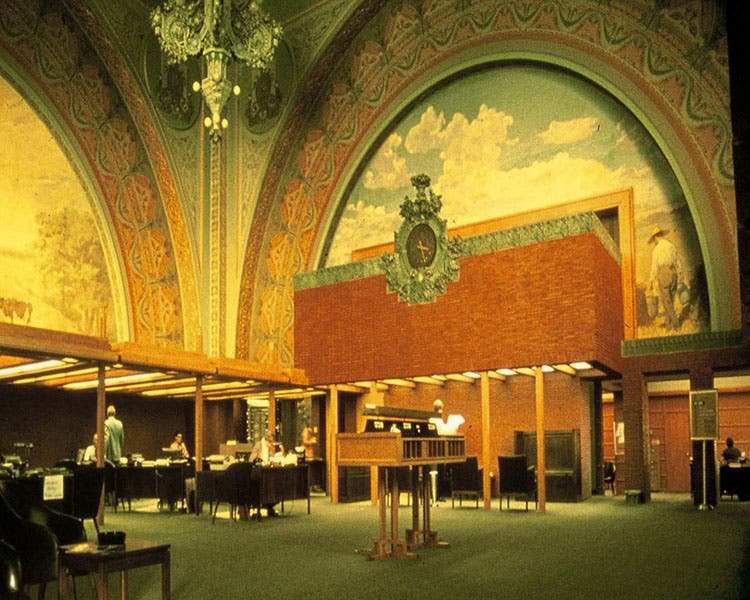

Chicago Stock Exchange, interior, designed by Louis Sullivan, 1893, photograph by author

An entirely different kind of architectural problem solved by Sullivan was creating a structure that had another new function of late 19th-century capitalism: the public American financial markets. His Stock Exchange Building (sixth image) is a majestic functional space for displaying instantaneous market data for all those gathered to observe and act upon. To enter this expansive space – which held hundreds of brokers, setting prices for various financial instruments – must have been a spiritually rich and dynamic experience. He created a vast open space with columns tucked into the corners, and daylight coming through giant windows and skylights, richly detailed with his ornamental system. Our seventh image shows another view.

Chicago Stock Exchange, interior, designed by Louis Sullivan, 1893, photograph by author

Toward the end of his life, Sullivan’s creation of the foundations of Modern architecture was submerged by the turmoil of World War One and its aftermath. The after-war devastation of Germany and the rise of Hitler sent a wave of German art and architectural intellectuals to the US and UK, who had a radically different version of Modernism, and who were invited to run many prestigious University architecture programs. Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, and others absorbed Sullivan’s dictum of functionalism, but simultaneously rejected the idea that architecture and art could be rich and complex in visual detail – providing a satisfying human psychological experience, as both Sullivan and Wright espoused.

Farmers and Merchants Bank, Columbus, Wisconsin, interior, designed by Louis Sullivan, 1919, photograph by author

This Bauhaus movement, as it was called, was driven by a Prussian-German severity which influenced many student bodies of that period and overwhelmed the grass-roots American architectural movement emanating from Chicago. This German style focused entirely on function, denying any importance to other elements of our built environment. This “new” Modernism morphed into a design system devoid of rich detail, ornament, color, texture – rejecting all these soul-satisfying aspects of human experience that Sullivan (and Wright) championed. The result was the ascendance of the flat empty surfaces of glass skyscrapers that are the antithesis, emotionally, of the work of Sullivan. While Sullivan’s Organic design philosophy lost to the Bauhaus mentality, his legacy exists in many real buildings dotted around the country and visited daily by those fascinated by another vision of the built environment.

Plaster cast of Sullivan facade ornament, photograph by author

We do not have space here to touch upon his remarkable series of Farmer’s Bank buildings throughout the Midwest (eighth image), or his technological collaboration with his engineer-partner Dankmar Adler, who was the primary engineering talent of the firm of Adler and Sullivan – especially their creation of many acoustically-rich theaters that are prized to this day; or his creation of a non-historical, architectural ornamental system (ninth image) presented in his published portfolio A System of Architectural Ornament; or the greatest autobiography I have ever read: The Autobiography of an Idea, which is the opposite of a minutiae-laden memoir, but rather a psychological odyssey of a young man’s search for true principles about art and life.

John Gillis is an architect in practice in New York and Kansas City. He is the author of Objective Esthetics, and Tidings of Joy and Comfort: Romanticism and Realism in Architecture, and Art in One Lesson.