Scientist of the Day - Louis Bourguet

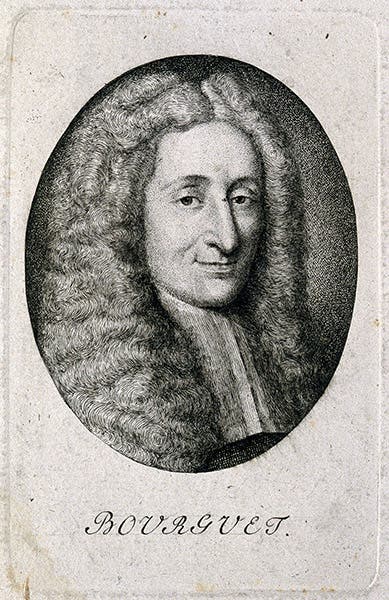

Louis Bourguet, a French/Swiss naturalist, philosopher, and historian, was born Apr. 23, 1678, in Nîmes. His parents were Huguenots, and when the Edict of Nantes was revoked in 1687, the family was forced to flee to Switzerland, first to Zurich, then to Bern. Louis himself settled in Neufchâtel, where he retreated from the life in business his father wanted him to follow, and adopted more scholarly pursuits. He learned Greek and Hebrew to go with his Latin and began to collect fossils, coins, and books. Bourguet made many trips to Italy, where he met Antonio Vallisnieri and Francesco Bianchini. He began a correspondence with the likes of Gottfried Leibniz and the Bernoullis, and the geologist John Woodward. In 1710, he was invited to become a member of the Academy of Science in Berlin.

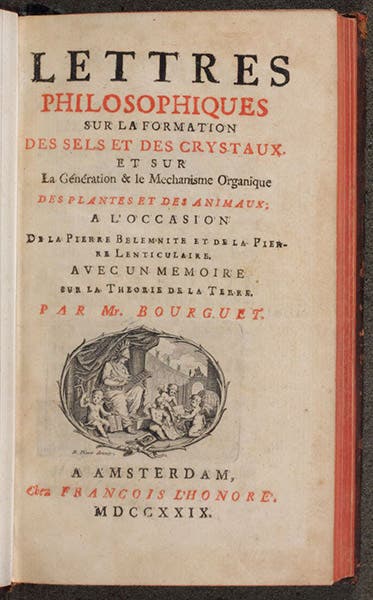

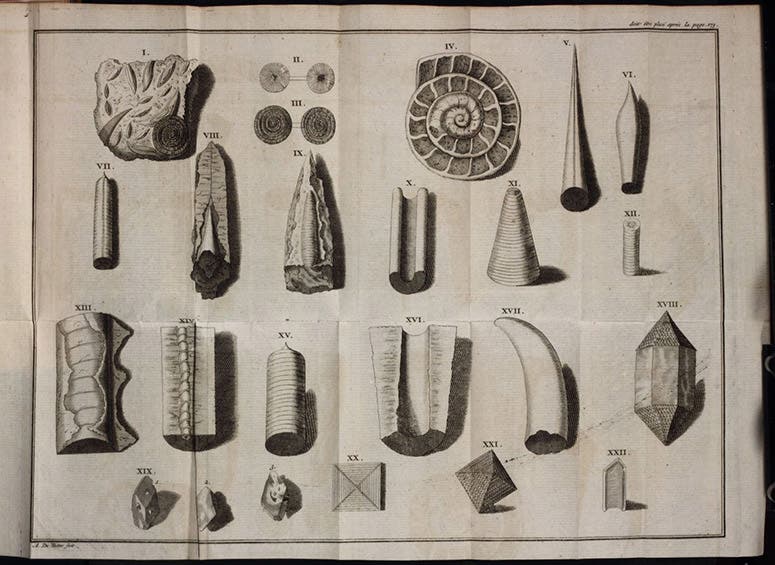

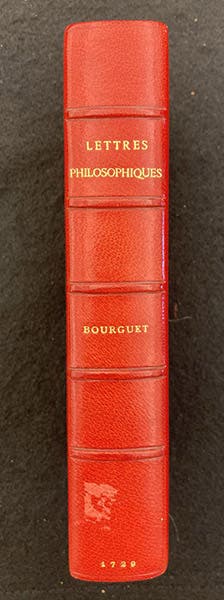

Bourguet wrote on a wide variety of topics, but he wrote a theory of the Earth, usually short-titled Lettres philosophique (1729), and another collection of letters called Traité des petrifications (1742). We have both of these in our collections. The first was a response to the theories of the origins of the Earth's crust published by Thomas Burnet, William Whiston, and John Woodward in England, and by Vallisnieri in Italy. Like Woodward and Vallisnieri, Bourguet believed that fossils would provide the key clues to a correct theory of the Earth. Like Woodward, but unlike Vallisnieri, Bourguet thought that fossils were distributed throughout the Earth's crust by the great Flood. In spite of the hundreds of letters he exchanged with Leibniz, Bourguet does not seem to have subscribed to the idea that the Earth was once molten. There is one folding plate in the book, which shows a variety of fossils, mostly belemnites (fourth image).

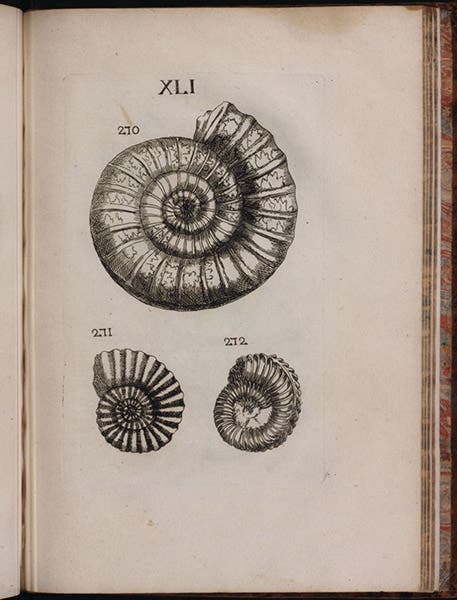

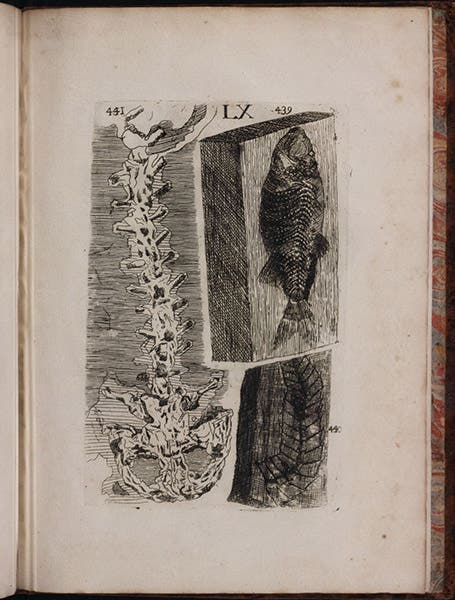

Bourguet's Treatise on Petrifactions is a more interesting book, because it contains 60 plates of etchings of fossils; they are exceptionally well drawn and printed, and, in our copy, are crisp and sharp. The fossils are almost all shells, such as mussels and scallops; there are 4 plates of ammonites, of which we show one (sixth image). We also show the last plate (seventh image), which unexpectedly contains, as fig. 441, a copy of the notorious Homo diluvii testis (“human witness of the Flood”), the remains of a giant salamander that had been found by Johann Jacob Scheuchzer and misconstrued as a human who died during the Flood. Scheuchzer was another of Bourguet's correspondents.

We bought our copy of Bourguet's Philosophical Letters at the first of the auctions of the Robert Honeyman collection in 1978, in one of my very first services as a library consultant. Many of the Honeyman books resided in custom-made red Morocco boxes. We now have many such boxes (we bought a lot at the Honeyman sales), but I cannot recall or find that I have ever shown a Honeyman box, so we do so here, with our last image.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.