Scientist of the Day - Lothar Meyer

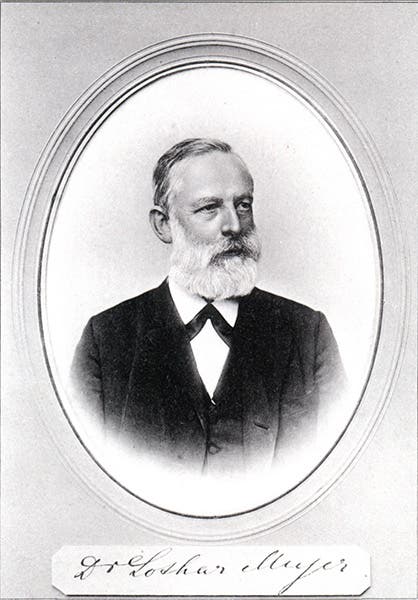

Lothar Meyer, a German chemist, died Apr. 11, 1895, at the age of 64. Meyer was one of six men to propose a periodic arrangement of the elements in the 1860s. He was four years older than Dmitrii Mendeleev, but since Meyer's education was delayed for about four years by health problems when he was young, the two men ended up being almost exact professional contemporaries. Meyer was educated at some of the best German universities, including Heidelberg, where he studied with Robert Bunsen, who had much to teach him, and he eventually ended up teaching at Tübingen for the last 20 years of his career.

Meyer (like Mendeleev) was much influenced by a paper given by Stanislao Cannizzaro at the first International Chemical Congress in Karlsruhe in 1860, in which Cannizzaro called attention to Avogadro’s hypothesis about atoms and molecules, which had been in eclipse for half a century, but which could be very helpful in determining the atomic weights of elements, a topic of intense discussion and disagreement among physical chemists at the time. Both Mendeleev and Meyer heard Cannizzaro’s paper in Karlsruhe, and both were quite excited by its implications for calculating atomic weights. When Meyer subsequently recalculated atomic weights, he noted various ways in which the elements, ordered by atomic weight, yielded periodic arrangements. He was working on a textbook at the time – Meyer was very interested in chemical education – and he included his first periodic table in the first edition of Die modernen Theorien der Chemie (1864). Oddly, we do not have Meyer’s textbook in our collections, not the first edition, nor any of the five editions that appeared in subsequent decades.

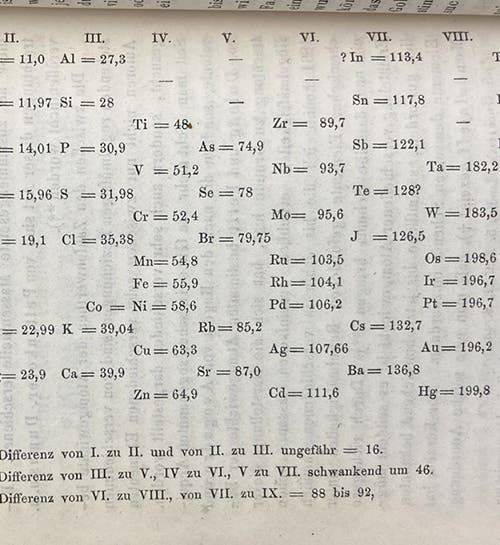

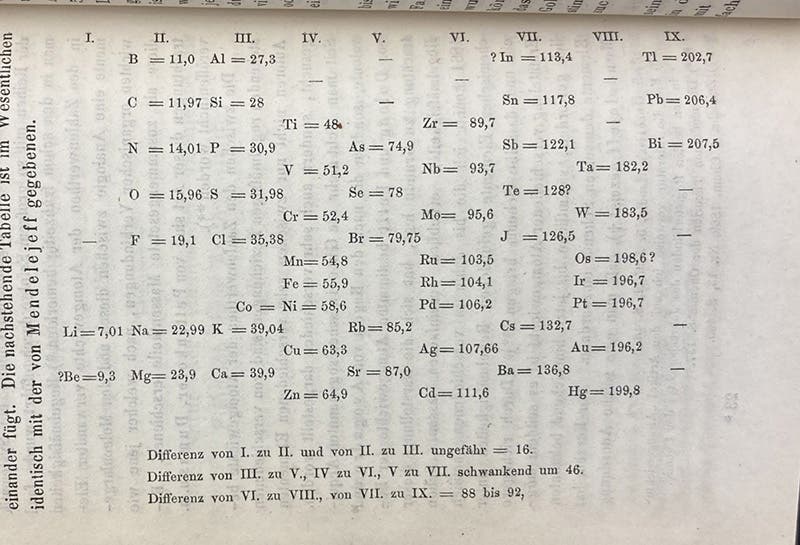

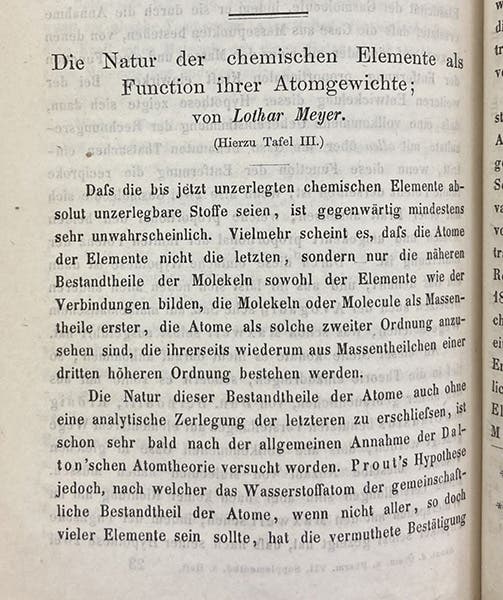

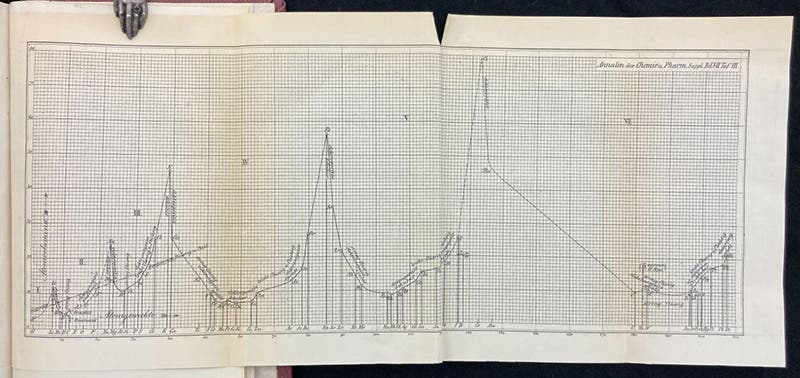

Fortunately, Meyer wrote a short paper for Justus Liebig’s journal, Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie, which appeared in a supplemental volume in 1870. We do have a run of this journal, and we show here the first page of the article (third image), a table, and a graph. The table (first image), type-set in the text, orders elements by increasing atomic weight coming down in the first column, and then continues in the second column, juxtaposing elements of similar chemical properties, such as C (carbon) and S (silicon), or F (fluorine) and Cl (chlorine) on the same horizontal level.

A folding lithographed plate at the end of the volume graphs atomic weight (horizontal axis) against atomic volume (vertical axis), with the chemically most active elements, such as potassium and sodium, at the cusps. Again, a periodic arrangement is readily apparent (fourth image).

If Meyer’s first periodic table, such as it is, predated Mendeleev’s by five years, why is Mendeleev everywhere recognized as the discoverer or inventor of the modern periodic table? This has been discussed in various forums by historian Michael Gordin, who points out that the six men credited with discovering a periodic arrangement were all interested in different aspects of the problem. Meyer was interested in chemical theory, and believed in atoms, and valency, and thought knowledge of chemical theory would help students learn chemistry. Mendeleev did not believe in atoms, or valency, and had no use for theory. But he did like the fact that his periodic table had holes in it, which suggested that there were undiscovered elements out there, ready to fill those holes, and he enthusiastically predicted their properties. He even named them, in advance. Meyer had no interest in making such predictions, for whatever reason. So when additional elements were discovered, and plugged into the table, they were seen as confirmations of Mendeleev, not of Meyer, and gradually Mendeleev’s name eclipsed Meyer’s. But it is interesting to note that when the Royal Society of London in 1882 presented their prestigious Davy Medal to the discoverer of the periodic table, it was awarded jointly to Mendeleev and Meyer.

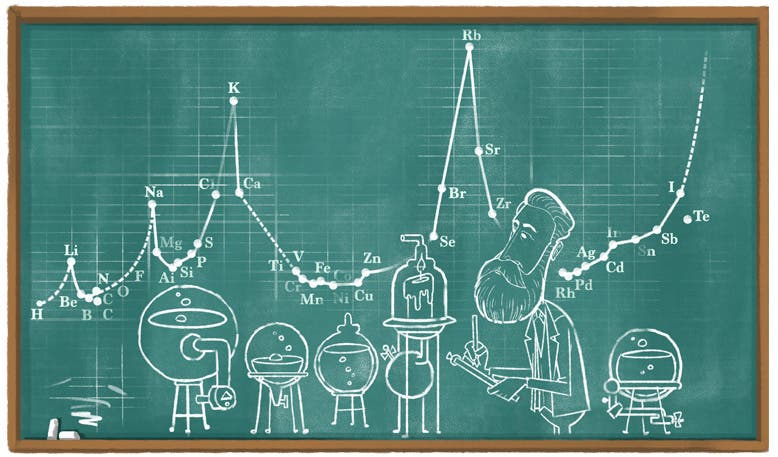

On Aug. 19. 2020, Google celebrated the 190th birthday of Meyer with a Doodle. It was one of their better efforts (fifth image). It was based on the atomic weights vs volumes graph of 1870 (fourth image), so I am glad we have a copy that we could include.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.