Scientist of the Day - Lewis Thomas

The Lives of a Cell: Notes of a Biology Watcher, by Lewis Thomas, 1974 (author’s copy)

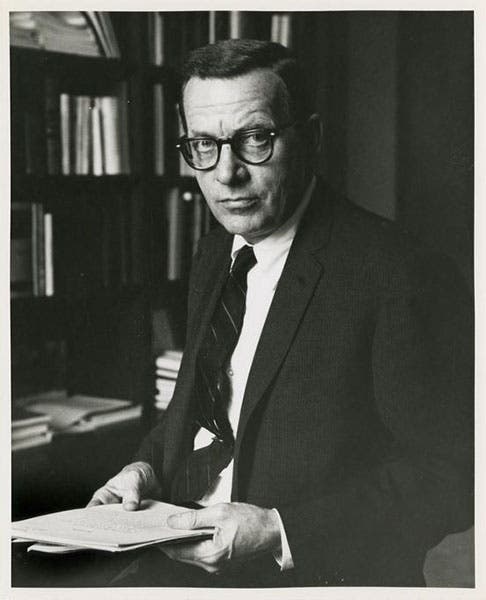

Lewis Thomas, an American physician, administrator, and essayist, was born Nov. 25, 1913. He attended Princeton and Harvard Medical School. Thomas was the president of the Sloan-Kettering Institute, a cancer treatment center in New York, when he was invited in 1971 by the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine to contribute a back-page essay to the journal each month. So Thomas started musing about such matters as the fact that the mitochondria of our cells are foreigners who carry their own DNA and reproduce independently of the cells that carry them (see last week’s post on Lynn Margulis), or the way that insects function as super-organisms--hunting, farming, fighting, and even taking slaves, just like us. Nearly 30 of these essays were collected and published in 1974 as The Lives of a Cell, which was phenomenally successful (for a collection of scientific essays), and won the National Book Award in 1975.

Portrait of Lewis Thomas, undated photograph, archives of the New York University School of Medicine (archives.med.nyu.edu),

I read The Lives of a Cell when it first came out, and I remember liking it immensely, but when I re-read it for this anniversary, I confess I had forgotten what a masterful prose stylist Thomas was – in my opinion, the best of them all, rivaled only by the early Loren Eiseley. He was a much more fluid writer, and more thoughtful, than Stephen Jay Gould, who is better known than Thomas for his scientific essays, for some reason, and Thomas’s personality, although very much present, was less obtrusive. Reading Thomas was like listening to some beloved world-traveling uncle, recounting his adventures by the fireside – like listening to Yoda, but with the subjects and verbs in the right place, and the adverbs and adjectives just perfect.

These first essays are now fifty years old, and the problem with science essays – especially ones slanted to the medical and biological sciences – is that they can easily become dated. Time has been kinder to Thomas’s essays, perhaps because he always has the long view, and the fact that he wrote before recombinant DNA and polymerase chain reactions doesn’t seem to affect the impact of his essays at all. Timelessness is a quality that the original essayist, Michel de Montaigne had, and very few essayists have had since, until Thomas.

Dust jacket, The Medusa and the Snail: More Notes of a Biology Watcher, by Lewis Thomas, 1979 (author’s copy)

Thomas was fascinated by insect societies, as we mentioned, and some of his essays focus on such matters as “the Hill,” which is what he calls an ant colony, a collection of millions of ants that functions in ways no single ant can imagine; in many respects, just like the Earth, which we think we understand, but about which, as an organism, we really do not have a clue. Some of Thomas’s observations are wonderfully trenchant. When talking about how we should go about searching for intelligent life elsewhere in the universe, he suggests that we should look for the presence of committees, since committees seem to be the hallmark of our own version of intelligent life. Spoken like an experienced hospital administrator.

Dust jacket, Late Night Thoughts on Listening to Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, by Lewis Thomas, 1983 (author’s copy)

Thomas published several more collections of his essays. The Medusa and the Snail: More Notes of a Biology Watcher (1979), and Late Night Thoughts on Listening to Mahler’s Ninth Symphony (1983), are two that I own and read with pleasure. Since I have little else to show for images, I include the dust jackets of these two volumes here, along with The Lives of a Cell.

I will conclude by quoting the first two paragraphs of the very first essay in The Lives of a Cell, so that you might feel the urge to read a little more by this remarkable latter-day Montaigne:

We are told that the problem with Modern Man is that he has been trying to detach himself from nature. He sits in the topmost tiers of polymer, glass, and steel, dangling his pulsing legs, surveying at a distance the writhing life of the planet. In this scenario, Man comes on as a stupendous lethal force, and the earth is pictured as something delicate, like rising bubbles at the surface of a country pond, or flights of fragile birds.

But it is illusion to think that there is anything fragile about the life of the earth; surely this is the toughest membrane imaginable in the universe, opaque to probability, impermeable to death. We are the delicate part, transient and vulnerable as cilia. Nor is it a new thing for man to invent an existence that he imagines to be above the rest of life; this has been his most consistent intellectual exertion down the millennia. As illusion, it has never worked out to his satisfaction in the past, any more than it does today. Man is embedded in nature.

Thomas died on Dec. 3, 1993, at the age 80.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.