Scientist of the Day - Lester Germer

Lester Germer, an American physicist, died Oct. 4, 1971, just shy of his 75th birthday. Germer is one of the few lucky physicists to have his name attached to a classic experiment. We have the Millikan oil-drop experiment that first determined the charge on the electron (1910), and the Michelson-Morley experiment (1887), which disproved the existence of an ether. And then there is the Davisson-Germer experiment of 1927.

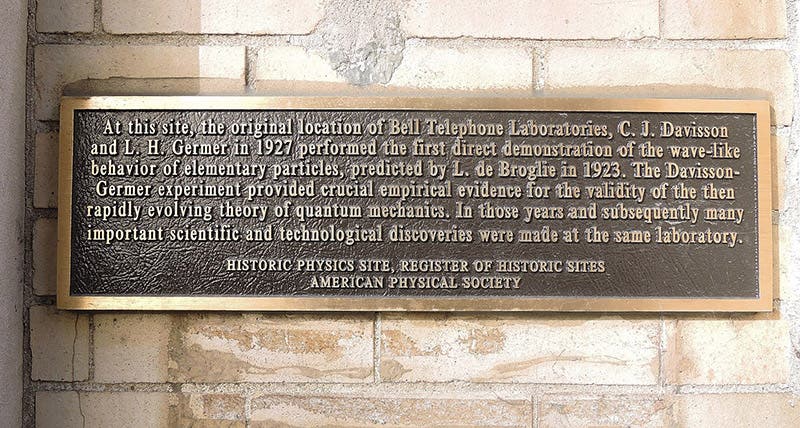

First paragraph of “The scattering of electrons by a single crystal of nickel,” by Clinton Davison and Lester Germer, in Nature, vol. 119, 1927 (Linda Hall Library)

In 1924, the French physicist Louis de Brogle had proposed that particles have a wave function associated with them, and he even predicted the wavelength of such waves for various particles. This seemed absurd at first – how could a particle behave like a wave and still be a particle? – but no one said nature is predictable, just that she is open to experimental inquiry. So Germer and his senior partner, Clinton Davisson, bounced a beam of electrons off the atoms in a nickel crystal. If you do that with light waves, you get a diffraction pattern, essentially a pattern of alternating light and dark zones. Germer and Davisson found that the same thing happens with electrons – they produce a diffraction pattern, and on measuring the length of the waves that would produce such a pattern, they got very nearly the wavelength that De Broglie had predicted for the electron. Albert Einstein had shown in 1905 that waves can behave like particles, and now Davisson and Germer were demonstrating that particles can and do behave like waves.

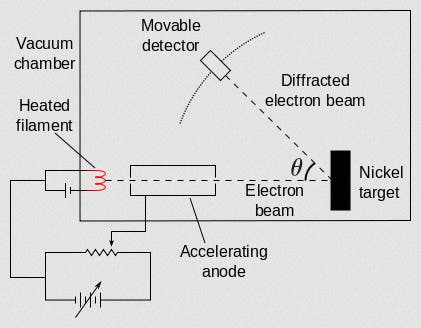

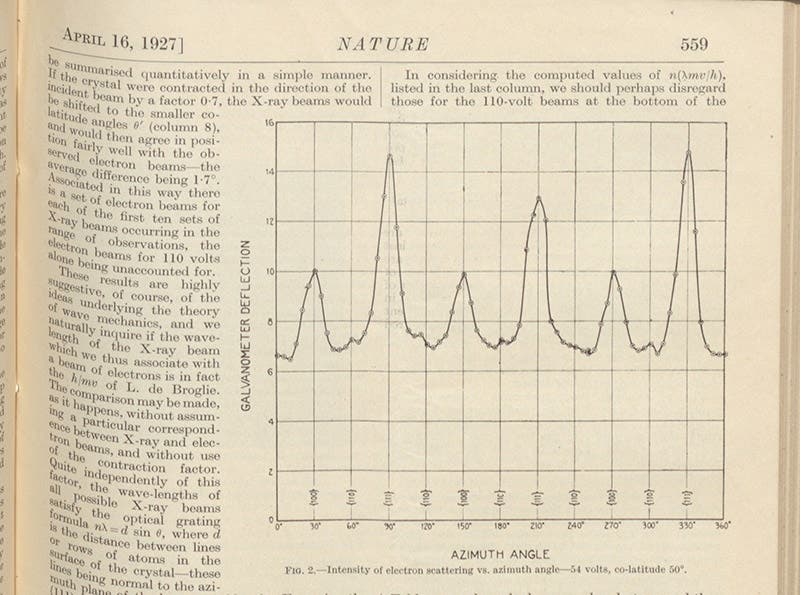

A diagram of the simple experimental set-up can be seen in our third image. Electrons are emitted with a known energy from an electron gun (which Davisson and Germer are holding in the portrait photograph), the electrons are reflected off the nickel crystal, and a detector that can slide along a circular scale detects the energy of the reflected electrons for different angles of reflection. At certain angles they detected few electrons, indicating that the electrons reflected from adjacent atoms were interfering. They published their initial results in a letter to the editor of Nature in 1927 (second image), which included a graph of electron intensity for the complete range of angles. You can clearly see the variation in intensity, caused by electron wave interference (fourth image).

A graph of varying electron intensity with changes in the angle of the detector, part of the Davisson-Germer article in Nature, vol. 119, 1927 (Linda Hall Library)

De Broglie received a Nobel Prize in 1929 for his prediction, and Davisson shared a Nobel prize in 1937 for the confirming experiment, but he did not share it with Germer, who was a junior assistant, and assistants are seldom rewarded with Nobel prizes unless the partners are clearly equal. But Germer did get his name attached to the now-famous experiment, which does not happen often. Germer became an ardent rock climber in his last quarter-century, and he never fell or had an accident until this day in 1971, when he was climbing a scarp and dropped dead of a heart attack. Whether this is a disappointing way for a rock climber to go out, I cannot say.

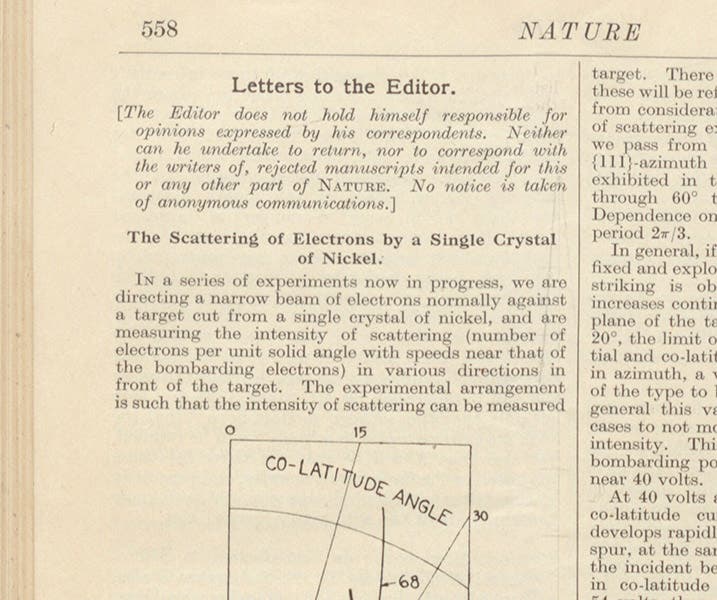

The site of the Davisson-Germer experiment at Bell Labs has been commemorated by the American Physical Society with a plaque (fifth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.