Scientist of the Day - Leslie Ward

Leslie Matthew Ward, a British caricaturist and portraitist, was born Nov. 21, 1851. Ward became noted for the caricatures he did for the weekly Vanity Fair magazine, some 1325 in all, it is usually said, but I am sure it is well over 1500. Most of his subjects were judges, politicians, or members of the peerage, but quite a few were scientists or engineers. I have noted 25 such caricatures, and no doubt there were more. For his birthday celebration, I have selected 7 of my favorites, including the very first caricature he ever did for Vanity Fair, in 1873.

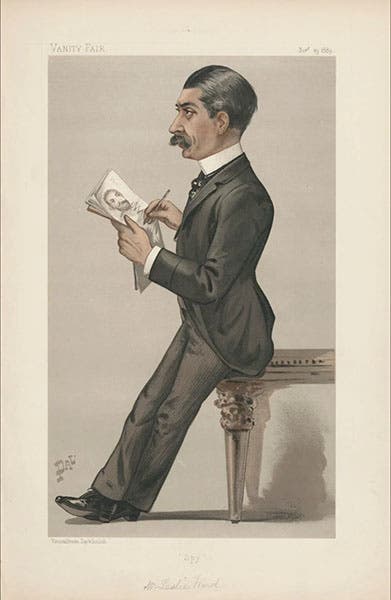

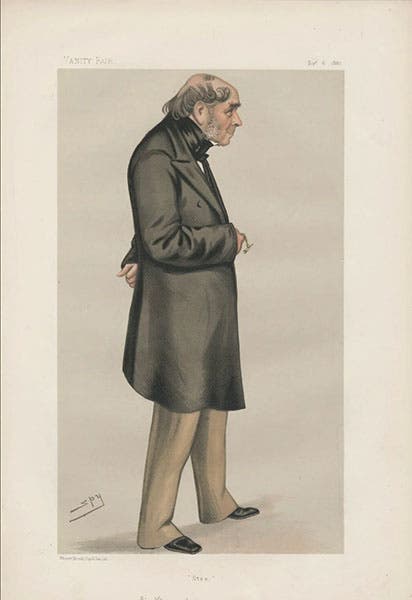

The policy of including a full-page chromolithograph caricature in each issue of Vanity Fair began rather early (the weekly was founded in 1868), and the first regular contributor was Carlo Pellegrini, who did the famous caricatures of Thomas H. Huxley and Bishop Samuel Wilberforce that have been often reprinted (you can see the Wilberforce drawing in our post on Wilberforce). When Pellegrini (who did caricatures under the pen name “Ape”) decided to take some time off, the editor cast about for a temporary replacement, and none other than John Everett Millais suggested young Ward, who was 21 years old at the time. Millais had seen a caricature Ward had done of the venerable comparative anatomist, Richard Owen, at a garden party, where Ward was struck by the "antediluvian incongruity" of “Old Bones,” as Owen was called when he wasn’t around. The editor liked Ward’s handiwork, and Ward’s watercolor was turned into a chromolithograph and appeared in the Mar. 1, 1873 issue of Vanity Fair (second image). Even after Pellegrini came back, Ward stayed on, submitting caricatures for forty years. The editor made him adopt a pen name, and he chose “Spy,” the signature you will see on all the caricatures here.

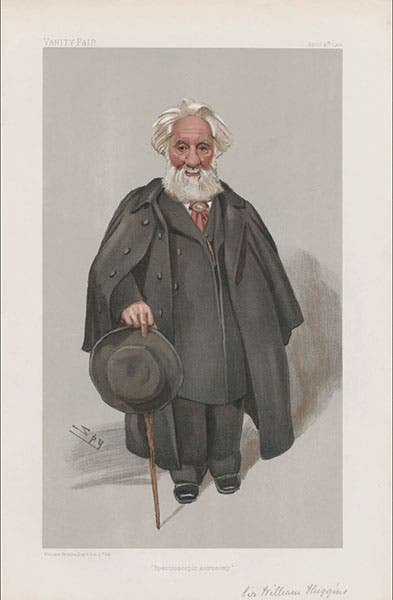

The rest of our caricatures are in chronological order, spanning the years from 1873 to 1903. It is often said (as in Wikipedia) that Ward’s caricatures lost their caricatural edge over time, as Ward grew less inclined to upset the rich and famous, but I would disagree. The last one here, of William Huggins, is just as delightfully exaggerated as the first.

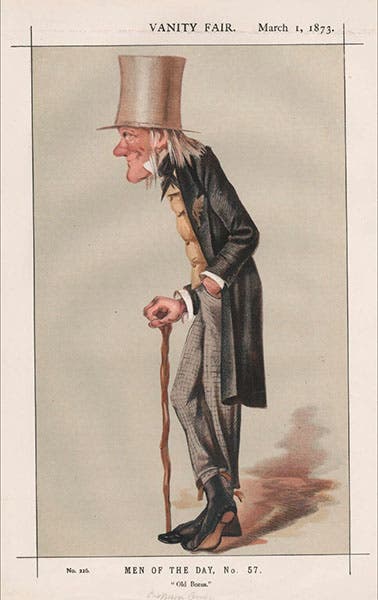

For each caricature, I will explain briefly who each of the subjects was, for those who might not know, and then link to a post, if we have done one. We begin (after Owen), with Henry Bessemer, who invented the modern method of making steel, the “Bessemer process," Ward’s caricature was published in Vanity Fair on Nov. 6, 1880 (third image). You will notice that the subjects of Ward’s caricatures are identified not by name, but rather by a caption that is a clue to the identity, as is “Steel” in the case of Bessemer. Here is our post on Bessemer, where we included the caricature.

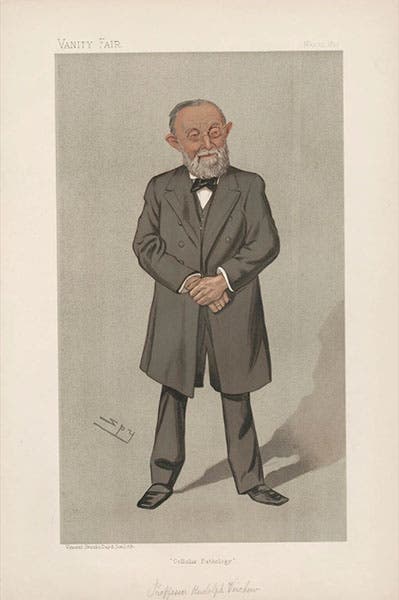

Rudolf Virchow was a German cellular biologist who said, in 1855, “omnis cellula e cellula” – “every cell comes from another cell” – thereby declaring that the cell is the basic unit of life. Why he was in the news in England in 1893 I do not know, but Ward did his caricature for the May 25, 1893 issue of Vanity Fair (fourth image). I have not done a post on Virchow, which is a bit of a surprise. I shall have to put him in the queue.

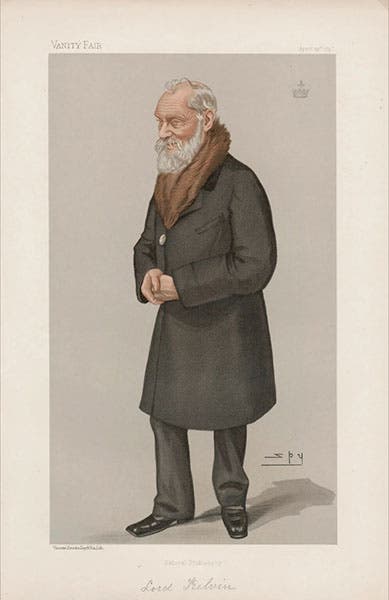

William Thompson, Baron Kelvin, was probably the most famous scientist in England in the 1890s, now that Darwin had passed on. In 1897, he was 73 years old and busy defending a young, 100 million-year-old Earth against upstart geologists and Darwinians. Ward’s caricature appeared in the Apr. 19, 1897 issue of Vanity Fair, with the caption “Natural Philosophy” (fifth image). The original watercolor of the lithograph can still be seen in the National Portrait Gallery, at this link. We did not include the caricature in our post on Kelvin.

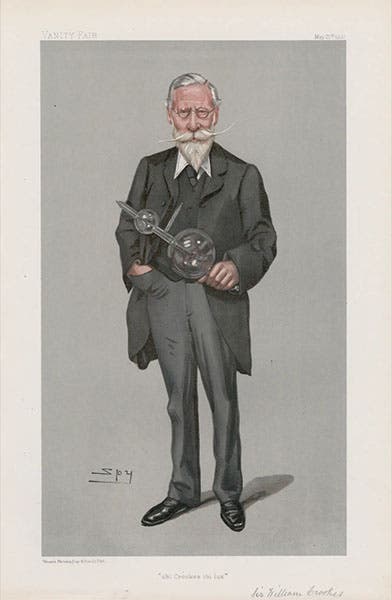

William Crookes was an English chemist who discovered how to make glowing gas tubes that were essentially precursors to cathode-ray tubes. Such devices were called “Crookes’ tubes,” and one of them was used by J. J. Thomson in the experiments that led to the discovery of the electron (the “cathode ray”) in 1897. Ward’s caricature differs from his usual in that he included a prop, an actual Crookes tube. It appeared in the May 21, 1903 issue, with the caption “Ubi Crookes ubi lux” (“where there is Crookes, there is light”) (sixth image). We included the original watercolor for the published lithograph in our post on Crookes.

Our last example of a caricatured scientist is one of my favorite Ward efforts, William Huggins. Huggins was a wealthy amateur astronomer and a pioneer in spectroscopic astronomy, who first discovered by analyzing spectra that some nebulae are gaseous, and that the star Sirius is moving away from us. Huggins was almost 80 years old when Ward did his drawing, and the finished product, published in the Apr. 9, 1903 issue, is the only counterexample one needs to refute the charge that Ward softened in his later days at the magazine. It is a marvelous piece of artwork.

Ward revealed some of the background to his caricatures, such as the story of encountering “Old Bones” Richard Owen, in his autobiography, Forty Years of ‘Spy’ (1915), which neither I nor the Library owns, but which I read online. But Ward had nothing to say about Virchow, Kelvin, Huggins, or Crookes, which I found disappointing. I would also like to have discovered why he never did a caricature of Charles Darwin.

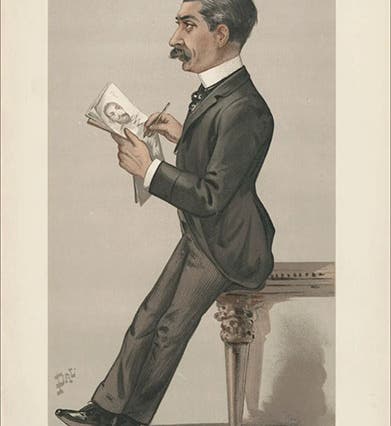

Presumably Ward did a caricature of himself, but I could not find it. So we settle for the next best thing, a caricature of Ward by Jean de Paleologu (“Pal”) that ran in the Nov. 23, 1889 issue of Vanity Fair (first image). The National Portrait Gallery in London has 1617 portraits by Ward, mostly caricatures, if you want to browse through 81 screens in succession, starting at this link.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.