Scientist of the Day - Lansdown Guilding

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

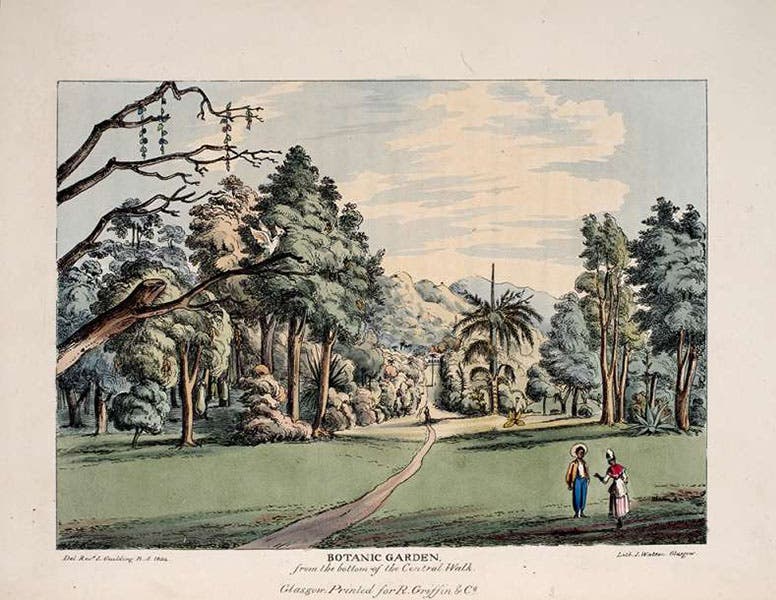

Lansdown Guilding, an English clergyman naturalist, was born May 9, 1797. Guilding was born in St. Vincent in the Caribbean, was educated at Oxford, and then returned to St. Vincent, where he took up a church rectorship and became a devoted supporter of the St. Vincent Botanic Garden. The garden, founded in 1765, was the oldest of what would become, by the early 19th century, an extensive network of British colonial botanic gardens, with Kew Gardens at its hub. The director at St. Vincent resigned in 1822 and was not replaced, and Guilding eased into the vacuum and apparently gained access to the papers of previous administrators. As a result, he wrote a book, which he published at his own expense: An Account of the Botanic Garden in the Island of St. Vincent, from its first establishment to the present time (1825). The work contains four hand-colored plates that give us an idea of how the garden looked in the early 19th century (third and fourth images), and the text includes lists of the plants grown at St. Vincent in the previous 50 years.

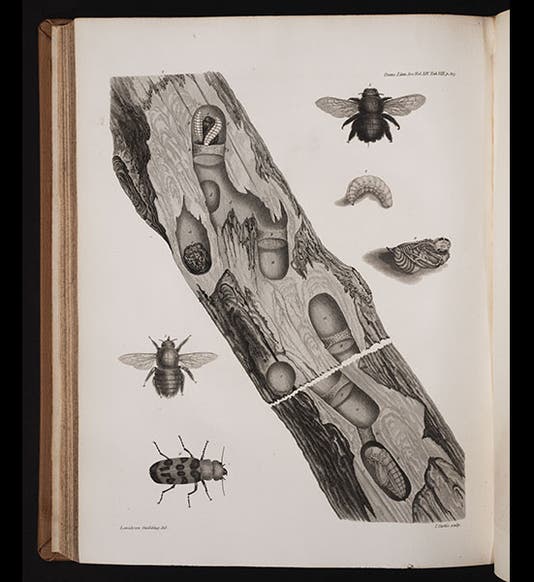

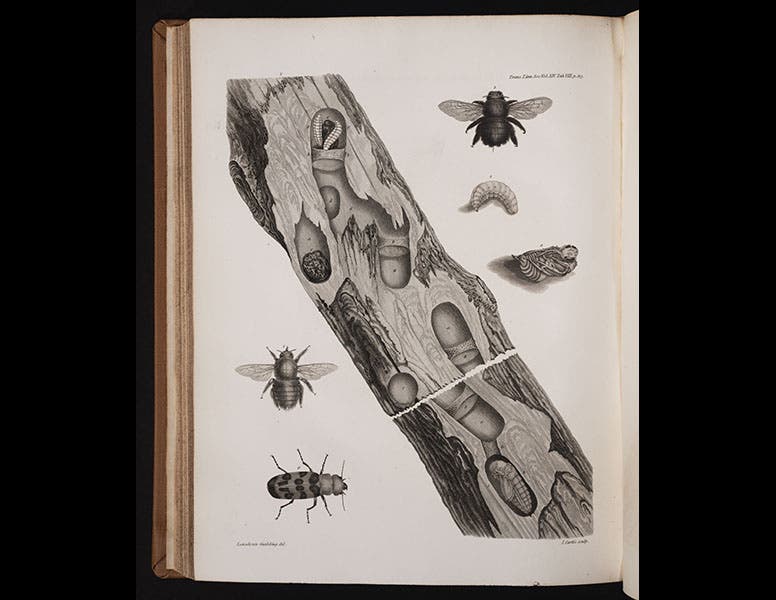

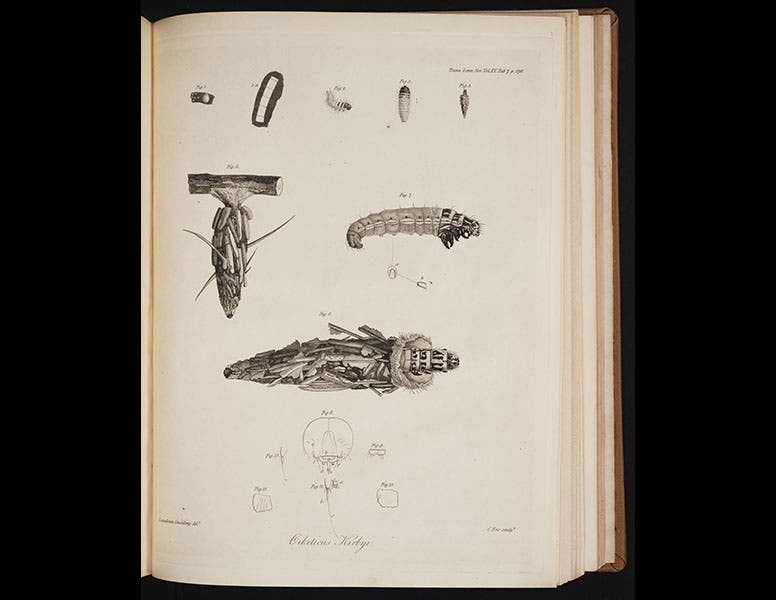

For a man who was supposed to be a botanist, Guilding seems to have been much more interested in insects. Most of the papers that he sent to the Linnean Society in London were entomological in nature. One of these, published in 1824-5, concerned a kind of carpenter bee, for which Guilding drew a rather striking illustration (first image). A year later he wrote about a moth larva that fashioned a portable cocoon out of bits of plant material, which it then hauled around from feeding site to feeding site. We now call these bagworms, and this appears to be a very early, if not the first, description of bagworms (second image). Guilding was pleased to discover how a female encased up to her neck in a fibrous bag manages to mate; you may consult his paper in the Transactions of the Linnean Society of London (1826-27) if you would like the details.

Guilding’s preference for bugs over buds is also apparent in a critique he wrote of Maria Merian’s beautiful folio, Metamorphosis of the Insects of Surinam (1705). In a plate-by-plate analysis, Guilding found many things wrong with Merian's depiction of butterflies and their larvae, especially when she mismatched them, but he hardly ever commented on her portrayals of plants. His review was published posthumously in the Magazine of Natural History (1834).

But Guilding did regularly send plants and drawings of plants to William Jackson Hooker, the future director of Kew Gardens, which Hooker often published in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, and while it is difficult to trace these, since Hooker had the material redrawn, we did find one find colored plate of 1827, showing a butter-nut flower, that Hooker explicitly credits to Guilding (fifth image).

Guilding died in 1831, of unknown causes, at the young age of 34.

We do not own Guilding’s Account of the St. Vincent Botanical Garden and would love to acquire it. The images above are from the copy in the SP Lothia Collection and available online.

This essay was greatly improved by contributions from the Library’s new residential fellow, J’Nese Williams, whose project focuses on, of all things, the activities of British colonial botanical gardens in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.