Scientist of the Day - Kristian Birkeland

Olaf Kristian Birkeland, a Norwegian physical scientist, was born Dec. 13, 1867. Beginning in 1898, Birkeland organized several expeditions to make geomagnetic observations at remote sites in northern Norway, Iceland, Spitsbergen, and Novaya Zemlya. Correlating his results with observations of solar activity and occurrences of Aurora borealis (northern lights), he was led to explain auroras by proposing that the Sun emits electrons that travel to Earth, are directed by the Earth's magnetic field to the North magnetic pole, and in the process generate auroras. The idea that electrons from the Sun could even reach the Earth was a novel one in 1900, as was the proposal that this solar wind causes the northern lights, and Birkeland's theory was rejected by mainstream geophysicists for decades, although it turned out to be essentially correct.

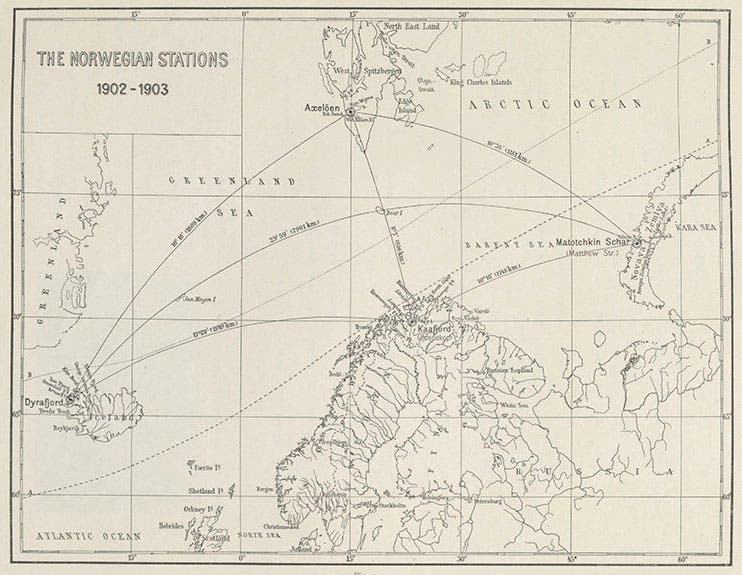

Map of the Aurora Polaris Expedition of 1902, from Kristian Birkeland, Norwegian Aurora Polaris Expedition, 1902-03, 1908-13 (Linda Hall Library)

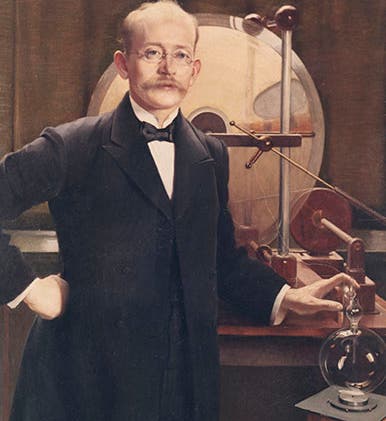

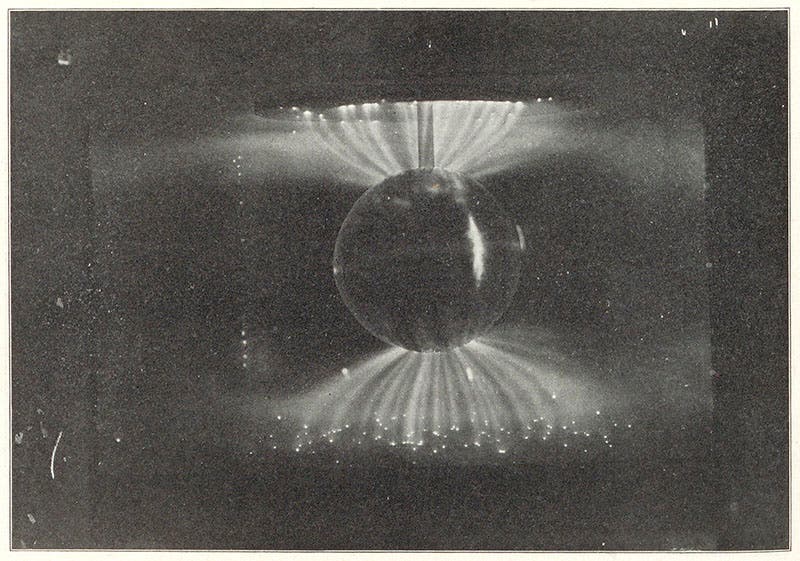

Motivated by reading about William Gilbert's terrellae, or miniature earth models, which were discussed in Gilbert's De magnete (1600), Birkeland constructed his own terrellas, somewhat larger than Gilbert's, and then built a glass vacuum chamber in which he could suspend a terrella, generate a magnetic field, and then bombard it with electrons. He found he could create displays quite similar to the Aurora borealis.

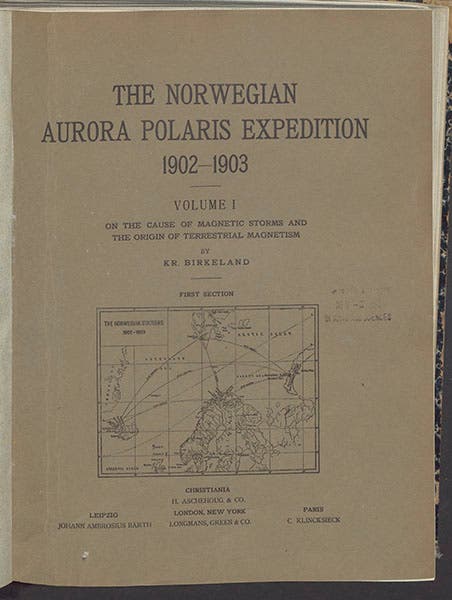

Front cover of Kristian Birkeland, Norwegian Aurora Polaris Expedition, 1902-03, 1908-13 (Linda Hall Library)

He discussed his ideas on the solar wind, the origins of aurorae, and his terrella experiments in a lavish book, The Norwegian Aurora Polaris Expedition, 1902-1903 (1908-13), that we have in our collections.

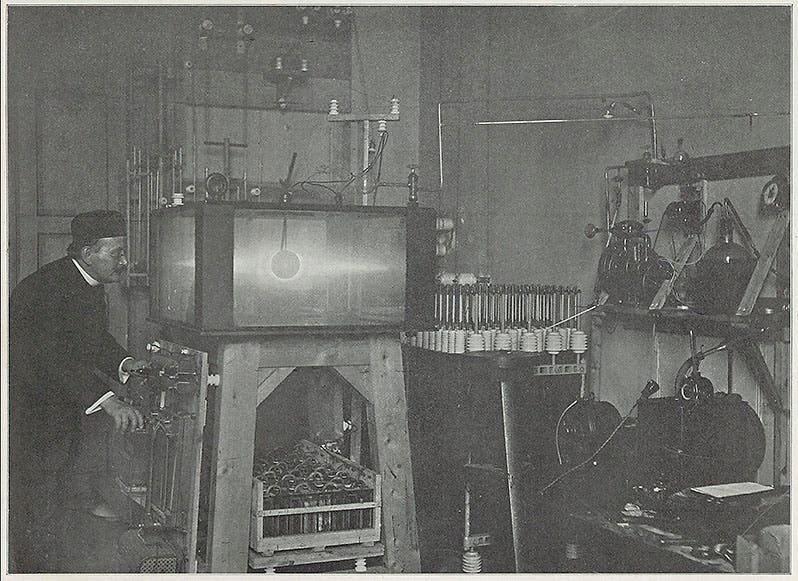

Kristian Birkeland with his terrella and its vacuum chamber in his lab in Kristiania (now Oslo), photograph, from his Norwegian Aurora Polaris Expedition, 1902-03, 1908-13 (Linda Hall Library)

The book opens with a map (second image) of the route of Birkeland’s expeditions (the same map can be seen in miniature on the cover (third image) and title pages of the publication), and includes a photograph of the terrella in its vacuum chamber, with Birkeland at the controls (fourth image), as well as several photographs of his artificially produced auroras (fifth image).

Artificial auroras generated by Birkeland’s terrella, photograph, from his Norwegian Aurora Polaris Expedition, 1902-03, 1908-13 (Linda Hall Library)

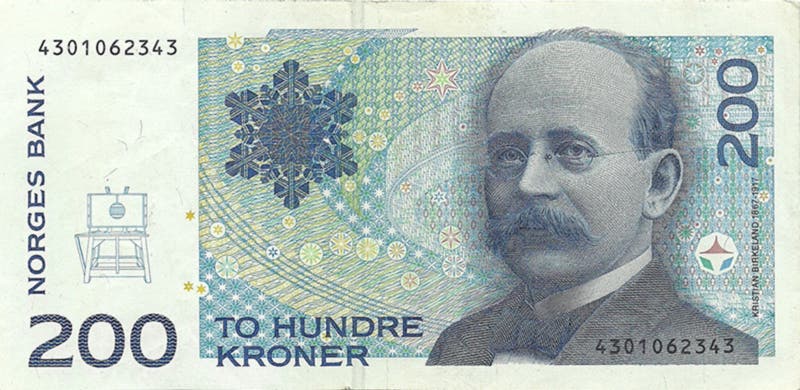

Birkeland died of an overdose of a sedative in 1917, only 50 years old, and did not live to see his auroral hypothesis generally accepted. He is now something of a hero in Norway, as he should be, and he was featured on the 200 kroner banknote of 1994, where you can see, on the front (sixth image), his portrait and a terrella in its vacuum chamber, and (on the back), the Birkland atmospheric electric currents named in his honor. Should you have an ultraviolet source handy, you could observe that Birkeland actually appears twice on the front of the note, the second time as the watermark (seventh image).

An original Birkeland terrella survives and has recently been restored to operation; it and its artificial auroras can be seen at the Auroral Observatory at the University of Tromsų, Norway.

Birkeland is well served by a biography that was published not that long ago, The Northern Lights: The True Story of the Man Who Unlocked the Secrets of the Aurora Borealis (2002), by Lucy Jago.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.