Scientist of the Day - Kathleen Butler

The Sydney Harbour Bridge opened for traffic on Mar. 19, 1932. It is one of the most iconic bridges in the world, especially if the view includes the equally iconic Sydney Opera House, as in our photo. It is a through arch steel bridge, with a span of 1650 feet, at that time the longest such span in the world. The top of the truss sits some 400 feet above the harbor surface. The bridge was the lifelong dream of Sydney engineer John Bradfield, and was designed and built by the English engineering firm of Dorman Long. But since it is the bridge’s birthday we celebrate today, and not that of any individual, we can tie the bridge to anyone we wish, and we choose Kathleen Butler, often referred to as the "Godmother of the Sydney Harbour Bridge.”

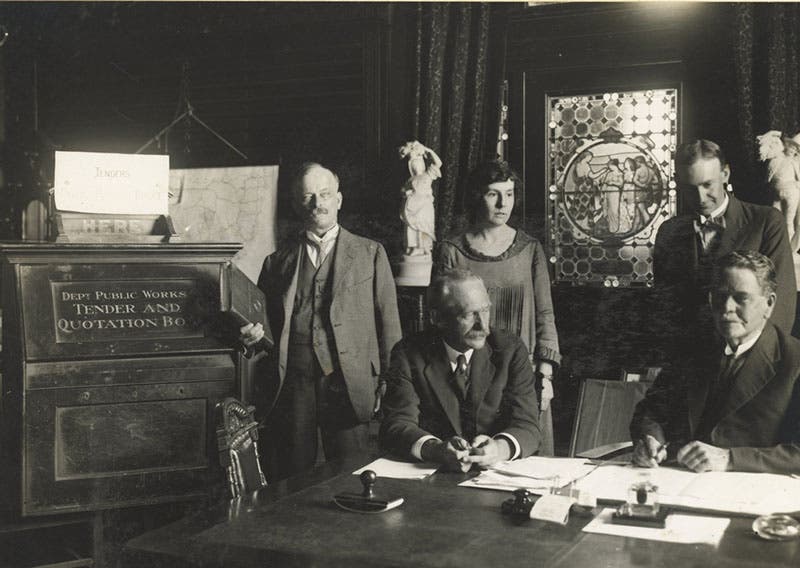

Miss Butler went to work as a clerk for the New South Wales Department of Public Works when she was 19. She somehow came to the attention of Bradfield, who was Chief Engineer of the department, and who was trying to convince the government to build a bridge across the harbor to Sydney. She must have been good at managing engineering details, for Bradfield gave Miss Butler more and more responsibility in managing the bridge project, especially after it was approved in 1922. She was given the title of Confidential Secretary, but she seems to have functioned more as a project manager. When tenders (bids) were solicited in 1924, she was right there when the bids were opened, as recorded in an often-reproduced photograph, since it was uncommon for women to be present at an engineering occasion such as this one (second image)

Butler was part of the decision group that studied the tenders intensively for six weeks, before the contract was awarded to Dorman Long in Yorkshire in northern England. The only instructions given the designers was that the Sydney bridge should look something like the Hell Gate Bridge built by Gustav Lindenthal over the East River in New York City in 1916 (you can see that bridge in images 2 and 3 of our post on Lindenthal). Miss Butler then hopped on a ship along with several Sydney engineers and sailed to England, where she took up residence at Dorman Long as Bradfield’s representative, while Dorman Long engaged in the lengthy (8-year) task of designing the bridge and fabricating the trusses for shipment to Australia. There survives a terrific photograph of Kathleen Butler embarking on SS Ormonde and steaming for England in 1924 (fourth image).

Unfortunately, Miss Butler's role in the Sydney Harbour Bridge project lasted for only three of those eight years. She married in 1927 and was forced to resign from Bradfield's staff, since married women were not allowed to do governmental work in Australia in the 1920s. But she was often invited to the construction site to participate in such ceremonial activities as breaking ground or drilling the first hole in a girder. There is a wealth of photos of the former Miss Butler so engaged, at this website.

Since this is the bridge’s birthday, and not Miss Butler’s, it seems okay to discuss a feature of the bridge that has always intrigued me and probably had nothing to do with Miss Butler, and that is the inclusion of four masonry pylons at the four corners of the bridge. These towers, which rise almost 300 feet from the harbor surface, were built at great expense, by masons imported from England, yet they have no structural function at all, since the weight of the truss is carried by the abutments below. The pylons add an appearance of weight and substance to the bridge that the public finds comforting. That, at any rate, was the justification for adding the pylons, which were not part of the original design. It reminds one of the (much smaller) towers on the Hell Gate Bridge. Originally, these were not connected to the steel arch, since they serve no structural function – there was a gap of about 12 feet between the two. This made people, even designers, so nervous that Lindenthal modified the design to make it seem that the arch was being supported by the towers, although in fact it is not. Often architects have to satisfy psychological needs as well as structural ones. Although one should note that the Sydney pylons, once erected, did find uses, as one was used to house a museum and gift shop, and another to vent fumes from a tunnel below, and the others to house maintenance vehicles and supplies. Sometimes function follows form.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.