Scientist of the Day - Karl von Schreibers

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

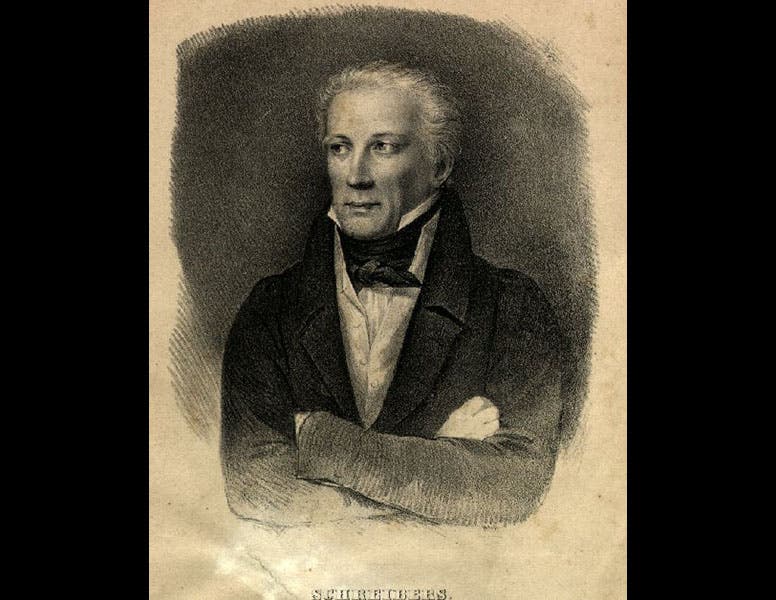

Karl Franz Anton Ritter von Schreibers, an Austrian naturalist, was born Aug. 15, 1775. Although trained as a physician, Schreibers took all of nature as his province, which made him the ideal choice to assume the directorship of the Vienna Natural History Museum in 1806. Although he was perfectly competent as a zoologist and botanist, his true love was minerals, and especially meteorites. The Vienna Museum had been collecting meteorites since the 1740s, but it wasn't until the turn of the century that scientists were finally convinced that meteorites were not some sort of atmospheric debris, but came to earth from deep space.

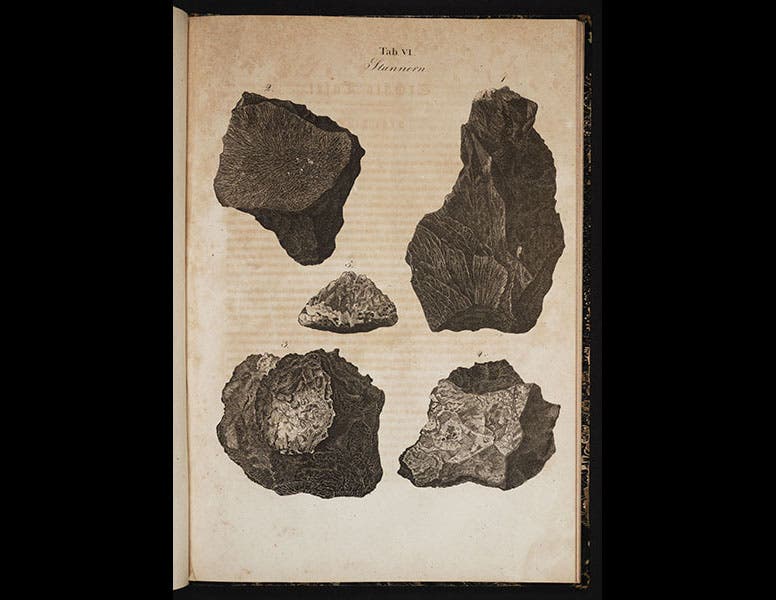

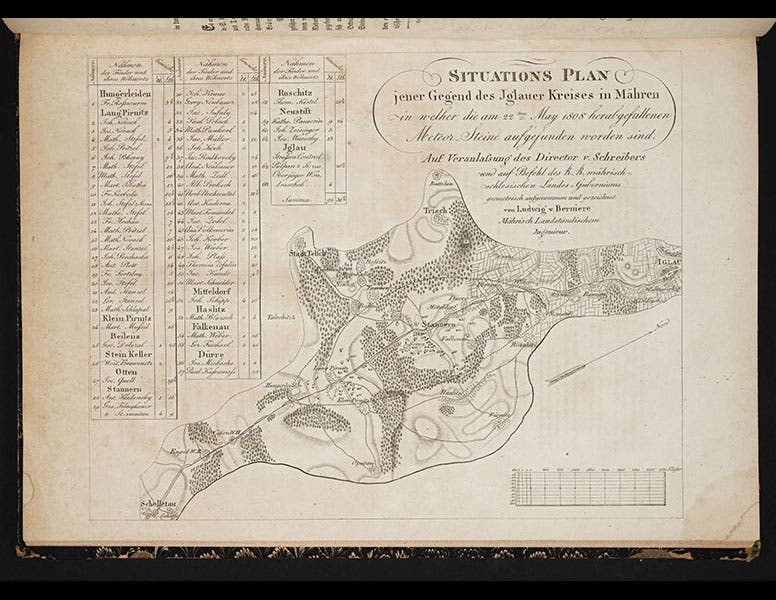

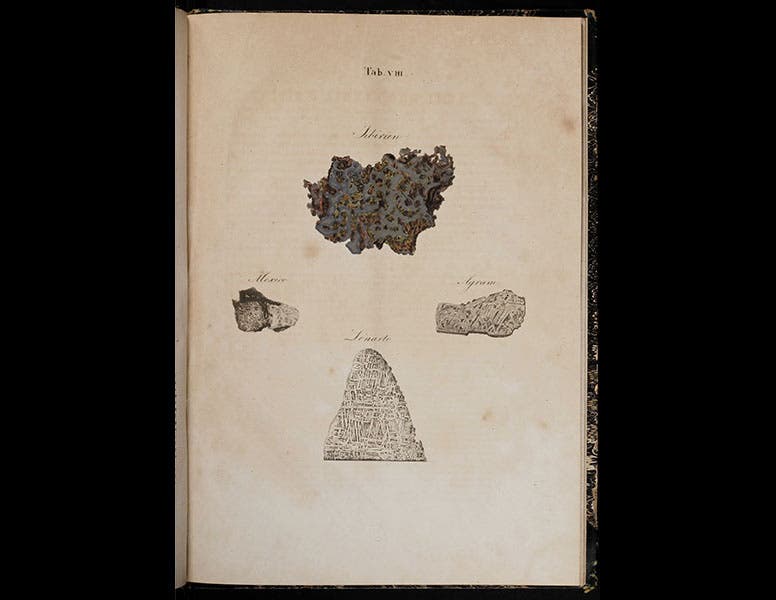

Schreibers' interest in meteorites intensified when a meteorite shower descended on the hamlet of Stonarov (Stannern in German) in Moravia (the modern Czech Republic), on May 22, 1808. Schreibers hastened there from Vienna, collected eyewitness testimony and meteorite fragments, and conveyed accounts and stones back to the museum. Twelve years later, when he published a book on the meteorites of the Vienna Museum, he included not only images of a number of the fragments (second image), but a strewnfield map, perhaps the first ever such map, showing not only the location of all of the 63 fragments, but the names of the villagers who collected each one of them (third image).

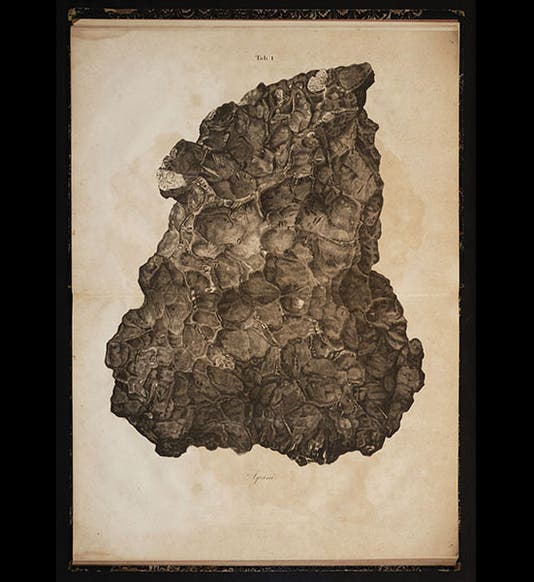

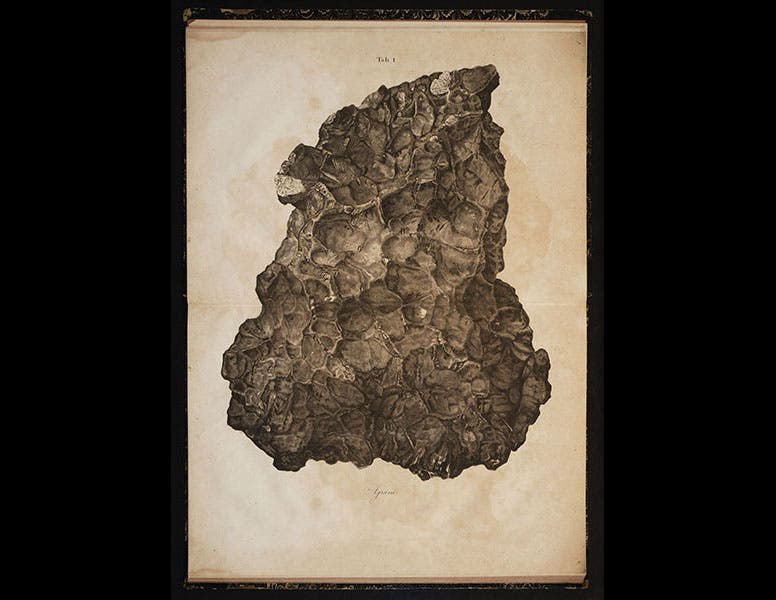

Schreibers’ book was called Beytrage zur Geschichte und Kenntniss meteorischer Stein- und Metall-Massen (Contributions to the History and Knowledge of Meteoric Stones and Irons, 1820); and it is significant for many reasons. It is the first ever to describe a particular meteorite collection. It has some of the most arresting images anywhere of famous meteorites, including the double- page plate that opens the book (first image), displaying the 86-pound chunk of iron that fell in Hraschina (Agram in German), Croatia, on May 26, 1751. The images in the book were printed by lithography, which was only invented around 1800; it may indeed be the first geology book anywhere to be illustrated with lithographs. And it revealed to the world that when an iron meteorite is heated in a flame, or rinsed with acid, it reveals a distinctive pattern, known as a Widmanstätten pattern, that only appears on meteorites (fourth image). Aloys von Widmanstätten had discovered this some years earlier (and was not in fact the first to do so), but most geologists learned about Widmanstätten patterns from a plate in Schreibers’ book that was actually printed directly from an etched meteorite. You can see it on our Scientist of the Day for July 13, 2015, when we featured Widmanstätten.

Schreibers continued to enlarge the Museum's meteorite collection until it was the finest in the world. Unfortunately, much of the museum was destroyed by fire in 1848 during an uprising. Schreibers was devasted, especially over the loss of the Library he had carefully built up; he retired and died four years later. But meteorites have a way of surviving fire and tumult, and Schreibers’ meteorite collection remained intact and continues to attract meteorite fans from around the world. Meteorite Hall, where the meteorites reside, was recently renovated and appears, from the photographs, to be quite spectacular (fifth image). The Hraschina stone is still on display (sixth image). The entire museum is a lovely memorial to Karl Ritter von Schreibers (seventh image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.